GP Gangsta Foundation members

In 2011 GP Gangsta, a hardcore kwaito group from Zola in Soweto, were working towards releasing their third album. But instead of focusing on the music, group member Nkosana Thwala, better known as Ntsimbi to his fans, became embroiled in a scandal.

“We’d been shopping our single to radio without much interest and then this story comes out,” tall, beefy group member Rev Tumza (Tumelo Mpanza) recounts in a township garage on Tuesday. It is the day the government is launching its annual 16 days of activism for no violence against women and children.

Long enough to fit two sedans in single file, the garage functions as the group’s headquarters. It’s situated on the block in Zola where GP Gangsta were born in 2002. Instead of cars, there are worn-out couches and chairs inside.

Tumza tells the story of the group’s metamorphosis into a foundation of activists highlighting the role men can play in combating gender-based violence. But the catalyst – Ntsimbi – is nowhere to be seen. Just Tumza and two foundation members, Philani Ngcobo and S’busiso Mkhwanazi, are present.

Like other members of the GP Gangsta Foundation, the men had been involved in 16 days events earlier in the day. Some joined a Johannesburg march to demand a national strategic plan to combat gender-based violence. Others attended a dialogue session held at the Jabavu Methodist Church.

Zola’s next big thing

Back in 2008 it looked like the group were set to be Zola’s next big thing. Their sound was a brusque mix of kwaito beats and vernacular rhymes, often using the first person to convey the triumphs and pitfalls of life in Zola. But despite their single Abogata being on heavy rotation on YFM, it never quite pushed GP Gangsta into the mainstream.

And then in 2011 they hit the headlines, but for the wrong reasons. Ntsimbi was in a bitter dispute with his estranged partner over access to their two children.

In the press, Ntsimbi was alleged to have locked the mother of his children in a room, pointed a firearm at her and forced her to consume an unspecified drug. It was to be the only headline the group would grab in 2011.

“The same people that didn’t want anything to do with us were suddenly calling Ntsimbi a kwaito star to spin the story in the media,” says Tumza.

Tumza recalls that this incident prompted the members of GP Gangsta and their circle to do a lot of introspection, especially about the nature of their relationships with their “baby mamas”. Ntsimbi eventually served a suspended sentence for kidnapping and assault.

“We’ve had a reputation for many things – positive and negative,” Tumza says. “But how do you take care of your child if you have no compassion for your baby’s mother?”

From introspection, he moved to action. In 2012, the GP Gangsta Foundation held a father and child fun day in Zola with jumping castles, food and music.

Men’s attitudes

Sonke Gender Justice, a lobby group aimed at changing men’s attitudes to gender issues, liked what it saw at the fun day. It recruited the GP Gangsta Foundation to get involved in its male circumcision drives and dialogue sessions in communities around Soweto.

Tumza attended one at the Jabulani Methodist Church, where he found himself arguing with a homophobe. “We also have our own vulnerabilities, but we learn as we grow.”

This year, the framing of men’s involvement in the 16 days of activism has caused controversy. Earlier this month, after a meeting in Benoni, the minister in the presidency responsible for women, Susan Shabangu, was widely criticised by nongovernmental organisations for her apparently tacit approval of reactionary patriarchal views expressed in what was supposedly a consultation event.

In a press release cosigned by 10 NGOs, the minister was called to task for “infantilising women” by suggesting that “men are supposed to be protectors of society”. An invited royal labelled feminism “unAfrican” and called shelters for abused women and children “cages” that should be shut down, saying issues of abuse should be dealt with in the home. Another traditional leader suggested that women should submit to their husbands.

No comment was forthcoming from the minister, despite several attempts this week by the Mail & Guardian.

Perhaps even more disturbing for gender activists was that the event was billed as consultative, but was actually “a rubber-stamping exercise” that yielded nil in the form of details for a national strategic plan to curb gender-based violence. On assuming her post, the minister put the national council on gender-based violence under review and emphasised the economic development of women as a priority.

Rands and cents

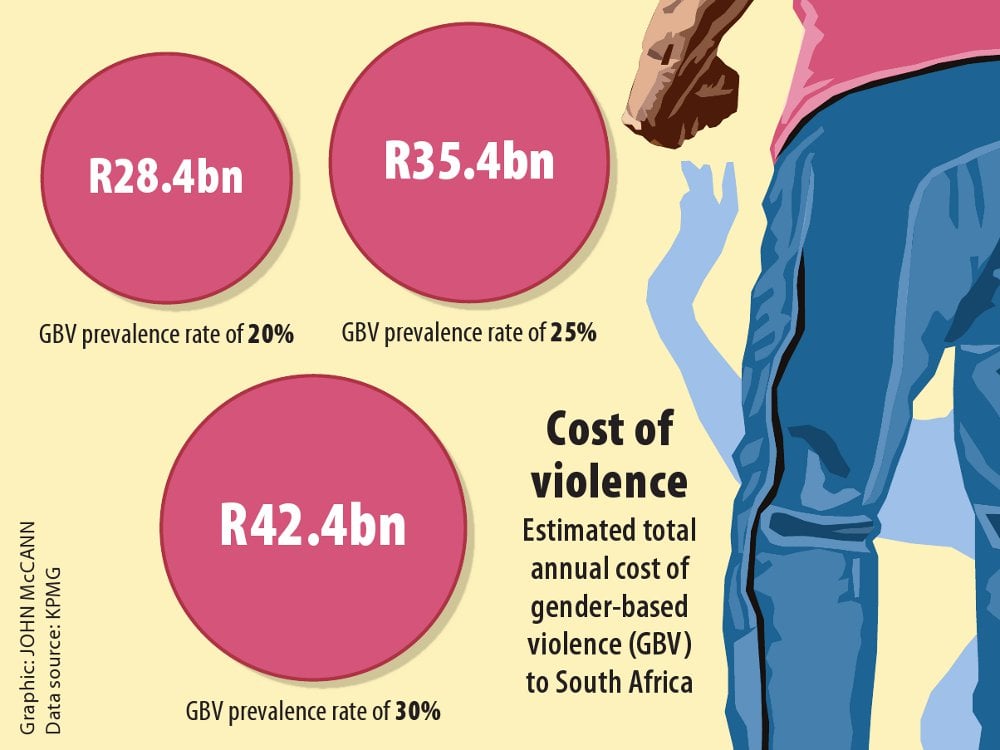

A recent KPMG study has put the national costs of gender-based violence at between R28-billion and R42-billion annually, suggesting that economic development is limited as long as gender violence exists.

Jabu Tugwana of People Opposing Women Abuse said the ministry cannot direct most of its resources to economic empowerment when one in five women experiences such pervasive violence that they encounter it at home, on buses, at school and in places of business.

“If this is not prioritised with funding, a budget and the implementation of laws, it renders our justice system impotent,” she said. “We need the system to work like how it worked during the World Cup; where you commit a crime, you get caught, tried and sentenced immediately.

“But as it is now – first of all, you get laughed at for being a lesbian, because you must be ‘taught a lesson’. Dockets get lost and it takes months to get a DNA sample verified.”

NGOs are desperate for the national strategic plan to be implemented. “Having timelines and a costed plan would help us reach a point where we are not responding after the fact,” said Nandi Msezane of the Ecumenical Service for Socioeconomic Transformation (Esset). “Developing a national strategic plan that was fully costed and programmatic assisted the fight against HIV and Aids.”

In 2010, the department of social development announced funding cuts to social services organisations. The following year, the department announced that it would pay only 75% of salary costs for social services organisations.

The Shukumisa Campaign, an advocacy group pushing for the implementation and development of policies related to sexual offences, studied the impact on 17 of the affected organisations. It found that they lost more than 100 positions, with many of them never being regained.

Rough life

GP Gangsta still make music. In their songs they often inhabit reprobate characters who tell slightly exaggerated tales of young people in Zola and beyond. But it is all based on the rough life that shaped them.

“I was raised by a single mother and I never once felt vulnerable,” Tumza says as we end our interview. “She was tough enough. My father was the weak one, who ran away from the situation.”

We emerge from the dimness of the garage and, in the warm late-afternoon sun, head a few houses down to a recording studio that belongs to GP Gangsta. The studio is filled with young men of all ages, tinkering with sound files.

You don’t need to look too hard here to see the advantage of having GP Gangsta as campaigners against gender violence.

It is a safe haven for these youngsters: a place run by their role models, who are people they trust, people whose unsanitised music mirrors their life stories – and therefore people whose messages they believe.