The group accused of plotting a coup in DRC in the Pretoria high court.

Almost two years ago, 20 men were arrested in South Africa, accused of a plot to overthrow DRC President Joseph Kabila. Last week, 15 of them were released. Although the state still maintains that a coup was under way, most of the men say they were innocently caught up in an elaborate money-making scam. So who’s conning whom?

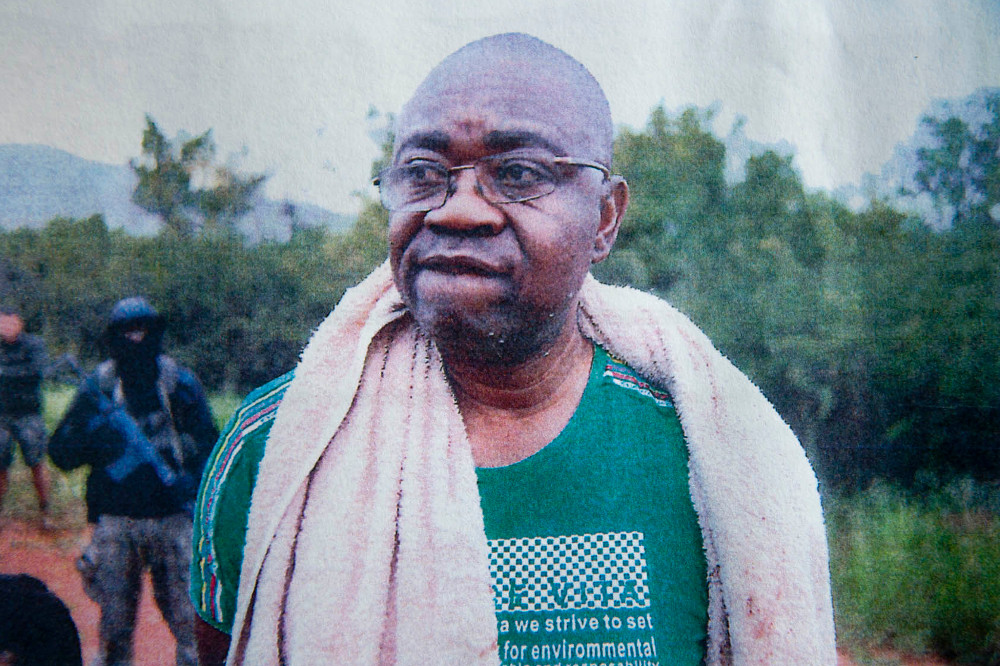

It was February 5 2013, a cool morning in the Limpopo bush. Nineteen men, most of them asylum seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), were woken at 4:30am. As they emerged from their tents they were greeted by a familiar face: the clean-shaven man before them was their “sponsor”, the man responsible for their special training, which had begun the day before.

But as they rubbed the sleep from their eyes, their “sponsor”, Lieutenant Colonel Noel Zeeman, pulled out his police ID card.

“I was astonished,” Kabuka Kilele, one of the men arrested that morning, recently said in the visiting area of Kgosi Mampuru II prison in Pretoria where he has been detained for the past 22 months.

Kilele, a Congolese-born entrepreneur who owned three hair salons and two internet cafés in Yeoville, Johannesburg, is the self-described mastermind of what he says was a long con, an elaborate scheme that involved mining in the mineral-rich area of Goma in the eastern part of the DRC where rebel gangs and government troops have clashed for years in a bid to control – and take a hefty cut of – mining trade. Kilele says he believed he would make a whopping $300 000 out of the deal.

But that’s not what the prosecution thinks happened.

That morning the men were taken from Limpopo straight to Pretoria and charged two days later at the magistrate’s court under the Foreign Military Assistance Act for engaging in mercenary activity, rendering foreign military assistance and collectively conspiring to commit murder.

In short, the 19 were accused of plotting to overthrow their head of state, President Joseph Kabila, and getting military training for their planned coup d’état on South African soil. Days later, Etienne Kabila, whose well-known surname might have been the cause of his participation in the coup, or the con, depending on whose story the court ultimately chooses to believe, was arrested in Cape Town.

Conspiracy and fraud

Initially, media reports claimed that the group was related to M23, a powerful rebel group that has been fighting DRC government forces for years. But days later, in an official statement, the National Prosecuting Authority set the record straight: “At this stage, no links have been established between the accused and M23.”

It would be the first of many twists and turns, which include government conspiracy claims and admissions of fraud, that take us to today, almost two years after the arrests and many court appearances.

The men were arrested while attending a military training camp.

Kilele, his brother Kilele Mukuti, Lunula Masikini and James Kazongo, an American citizen of Congolese descent, remain in prison.

Last week Kabila was released on bail but still faces the same charges as those who remain behind bars.

The day before Kabila was released, 15 of the original 19 were also released but their charges were dropped because of a lack of evidence. The men maintain – as they have throughout their time behind bars – that they believed their training in the bush was about getting an anti-rhino poaching certificate.

No knowledge

They say they knew nothing about military exercises and being prepared to fly back to their home country, join the Congolese rebel group Union of Nationalists for the Renewal of the DRC (UNR), also known as the Alliance Des Forces Pour La Recuperation Du Congo (AFCR), and kill Kabila and 14 of his Cabinet ministers and take over the government.

Confused?

Well, you should be. This intriguing tale of Congolese rebels and coups, mining deals and military training, rhinos and secret agents, is about who the court will ultimately believe. Who is conning whom?

The state, in its case against the men, have alleged in court papers that the accused were dissatisfied with the leadership of their country and made contact with two undercover agents from the Hawks, who went by the names of James Jansen and Joe Bressler, to procure weapons and training to orchestrate a coup.

But the accused, in statements made to this reporter during several interviews over the past few months, claim that they were executing a con with the agents as their targets. In a series of meetings with the agents and other men claiming to be interested in mining concessions in the DRC, Kilele says he led the agents on in order to secure a promised cash payment of $300 000 from a man identified to them as the “sponsor”, who was actually Zeeman from the Hawks.

“Hearing this amount of money, I say I have to do whatever they want to get the money,” says Kilele.

Ringleader

By his own admission, it was Kilele and not Kabila or Kazongo who orchestrated the events that led to their arrest.

Kilele says he was led to the agents, through several connections, and believed they wanted to do mining “business” with his friend Kabila, who they believed was related to the president and therefore would have reliable connections and influence in the DRC.

According to court documents, Jansen and Bressler first met Kilele at a restaurant in Norwood, Johannesburg, in September 2012. At a subsequent meeting, the prosecution states, the agents met Kilele at a restaurant in Pretoria where he introduced Kabila as the leader of the rebel group UNR.

James Kazongo came from the United States to join the scheme.

Kilele claims that was merely part of their con – to present a rebel group that sounded powerful enough to take over key mining operations so they could win the favour of the sponsor.

According to the state, plans were set up for military training for a group of Congolese, which would commence in late January 2013. Prosecutors say this was when Kilele indicated that “he had identified individuals presently in South Africa to receive military training, some of whom were veterans whilst others had no military experience whatsoever”.

Part of the scam

The prosecution then cites a follow-up meeting in January during which the name of General William Amuri Yakutumba, whose Goma-based Mai Mai Yakutumba faction is widely feared, was raised by Kilele. The agents were given a disc with photographs and footage of Kilele and Yakutumba and his soldiers, as well as “a piece of foil which contained a small amount of gold grains” from the region in the DRC that their rebel group apparently controlled.

Kilele says that is because, as part of the scam, he travelled earlier that month to meet Yakutumba just outside Uvira, in the eastern DRC, where he offered Yakutumba $20 000 to pose in the photos.

The training camp in Modimolle, Limpopo, where the men were arrested.

By this time Kabila had dropped out of the scam and Kilele says he found a suitable replacement in Kazongo, who flew in from the US.

“I met Kilele, who said he had some ‘ co-opération‘,” claims Kazongo.

The term, co-opération, is synonymous in the Congolese community with dealings “that lead to money”. Kazongo says he was promised $100 000 to represent the group and eventually collect money from the sponsor.

Anti-rhino poaching training

Meanwhile, Kilele reached out to the Congolese community in Yeoville, many of whom are desperate for any kind of work, telling them that his group was offering seven weeks of anti-rhino poaching training, which would come with a certificate to help them get work, and a lump sum of $2?500. In two days, he had gathered 15 men.

The 15, who were released last week, claim that this was their first involvement in the “plot” and that they were acting on promises made by Kilele about the rhino conservation training.

On February 4 2013, 19 men made their way to Limpopo, where the training was to take place.

The state claims that Kazongo, Kilele and Masikini, during the drive to Limpopo, “emphatically” confirmed that all the men were “committed to military training, which would enable them to return to the DRC to effect a coup d’état and take back the DRC for the true Congolese people”.

But Kilele claims the conversation was elicited by Jansen.

“[He] started a conversation and said … ‘Africa is destroyed by their leaders because of corruption, even our country is full of corruption’ … It was a provocative conversation on our side.

“We commented about the current situation in our country, which he was recording [as] evidence against us.”

Bush camp

When the group arrived at the bush camp, the men say they were welcomed by Jansen and introduced to their trainer, who wrote their mission statement on a clipboard chart: “We, the AFCR, will take back the Congo by coup d’état and conventional warfare.”

But, according to the prosecution, the trainer was only responding to their commitment to stage a coup.

The men were arrested the following morning.

In the end, both accounts end the same way – in a police vehicle heading to Pretoria.

After a month-long battle in court, in March 2013, all the men were denied bail and were jailed until last week.

The trial of the five still facing charges resumes on January 26.

The past is another country

Days after their release from Pretoria’s Kgosi Mampuru II prison, 15 Congolese men are rediscovering the harsh realities of life on the outside.

David Bakajika, who declared on release that “it’s better to live in hell than [in] a South African prison”, now says that he is worried about his future.

“I am father of five kids. I have to work to take care of my family, but the way they portrayed us, there is nowhere we could find jobs. I don’t know how I will fulfil my duties as a father.”

But, among the 15, he is one of the lucky ones – he has a place to live. While in prison, his older sister, Marie Muyembi, sublet part of their two-bedroom bungalow in Johannesburg’s Yeoville suburb to several families. The extra income helped her to make rent payments, which he was responsible for before his detention.

Simon Mbuyi Mukuna was not so lucky. His wife lost the room they were renting in Berea, Johannesburg, and eventually had to move into a shelter in the suburb of Bertrams. When he went to meet his family there, there was no space for him.

“Since I was released on Friday, I don’t have a place to stay. I asked [at] the Congolese church and I am sleeping there. My wife and kids are still at the shelter,” he says.

David Bakajika is worried about his future. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

The men say eight of them sleep at the church in Yeoville. Mussassa Tshibangu, who recruited two of the men for the scheme that landed them in prison, also sought shelter there with his wife and young daughter.

“The problem is so bad. The time I was released my wife was happy to see me, but she was also unhappy because we lost the place where we were staying before. There was no money to pay rent; the church gave [her] a place to sleep. We have to wake up at 6 o’clock in the morning to give them a space to pray.”

Besides the issues of employment and lodgings, some of the men have returned with a sense of paranoia.

“I am free but I [don’t] feel safe … because I am a victim of a plot by the South African government and the Congolese government,” says Jean-Pierre Lerulwabo, who has no family and no fixed address in the country.

Then there is the trauma of almost two years in prison.

“They submitted us to torture, morally and physically, and we were locked in a single cell for 23 hours … today I am free, but with the bad memories of prison.”

Simon Mbuyi Mukuna is sleeping at the Congolese church. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

A spokesperson for the prison says such claims “are thoroughly investigated’.

Despite their difficulties they say they have received offers of support. The International Committee of the Red Cross had a meeting with the men on the day of their release. A follow-up meeting is slated for next week.

It was the only organisation that visited them during their time in prison, the men say.

Their thoughts, although firmly occupied with survival, still return to the injustice they believe they faced.

“We do believe that they are some good judges like Billy Mothle [who presided over the case]. He’s a qualified man,” says Bakajika. “The problem is the justice system is not free.”

The key players

Accused no 4

Kabuka Kilele

Kilele was an entrepreneur in Johannesburg’s Yeoville. He owned three hair salons and two internet cafés. He introduced Etienne Kabila to the men later revealed to be part of the sting. When Kabila pulled out of the arrangement, Kilele installed James Kazongo as his replacement. Kilele brought the 15 recently released men together for anti-rhino poaching training and had the most contact with the Hawks.

Accused no 2

Lunula Masikini

Masikini has been living in South Africa since 1993 but often travelled back to the Democratic Reublic of Congo (DRC). In 1999, he was arrested by government forces during the second Congo war, but he escaped from prison and returned to South Africa in 2001. He drove Kilele to meetings with the agents. In late 2012, he made the initial contact with Kazongo and asked him to be part of the arrangement.

Accused no 1

James Kazongo

Born in the DRC in 1967, Kazongo was at school in Belgium before moving to the United States in 1981. He settled in Philadelphia. He arrived in South Africa in late January 2013 after receiving a call from Masikini about joining their scheme.

Accused no 3

Kilele Mukuti

Mukuti arrived in South Africa via Mozambique in 2002 with his brother Kabuka Kilele. He has been a recognised refugee in South Africa since 2007. He and his wife, Annette, have three South African foster daughters. He was working as a moulder at Wayne Plastics in Roodepoort before his arrest.

Accused no 20

Etienne Kabila

Despite his well-known last name, a high-level government official in Kinshsa says he is not related to DRC President Joseph Kabila. The co-accused describe him as an “enigma”. Kabila allegedly posed as the leader of the Union of Nationalists for the Renewal of the DRC, also known as the Alliance Des Forces Pour La Recuperation Du Congo. After sharing a flat with Kilele in 2002, he moved to Cape Town where he has been living ever since. He is currently out on bail.

The investigating officer

Lieutenant Colonel Noel Zeeman

Part of the South African Police Service’s anti-terrorism unit, Zeeman has more than 23 years experience in the force. During the trial, he intimated that the investigation began after receiving information from a “credible” source that a group of Congolese rebels were looking for mercenaries to help with a coup. He posed as the “sponsor” during the sting.

The agents

James Jansen and Joe Bressler

Undercover Hawks agents Jansen and Bressler (not their real names) first met Kilele and Masikini, who were then serving as emissaries for Etienne Kabila. The accused say they were all made offers of cash. The agents say they believed throughout the sting that the men were seeking to overthrow Joseph Kabila.

Timeline

2012

September 5: Kabuka Kilele and Lunula Masikini meet Lieutenant Colonel Noel Zeeman. They are told that Zeeman is the “sponsor” visiting from overseas.

September 11: Kilele and Masikini meet Zeeman again. They are told that Etienne Kabila has “agreed to do business with them”.

September 20: Kilele and Masikini meet the Hawks agents, known as James Jansen and Joe Bressler who are working with Zeeman, for the first time at Capello’s in Norwood.

October 10: Kilele introduces the agents to Kabila in Pretoria.

November 8: Kilele meets agents Jansen and Bressler to inform them that Kabila is “no longer interested in their business”. That evening Kilele receives an email from Jansen increasing the sum offered to $300 000.

2013

January 11: Kilele travels to Uvira in the DRC to meet General William Amuri Yakutumba. Kilele promises to pay Yakutumba $20 000 to pose with him and his soldiers.

January 19: Kilele returns to South Africa.

January 22: Kilele and Masikini hand over photographs, footage and gold samples taken in the DRC to the agents.

January 25: James Kazongo arrives in Johannesburg from Philadelphia.

Kilele Mukuti is the brother of Kabuka Kilele, the self-described mastermind of what he claims was an elaborate con.

January 28: Kilele Mukuti, Kilele’s younger brother, joins Kilele and Masikini for a meeting with the two agents.

January 29: Kilele, Masikini and Kazongo meet the agents. Kazongo is promised $100 000 from the “sponsor”.

February 2: A friend of Kilele, David Bakajika, is asked to round up recruits for “anti-rhino poaching” training. Kilele promises $2 500 and a certificate to each recruit.

February 4: Masikini, Kazongo, Mukuti, Kilele and 15 men meet the agents and are driven to a bush camp in Modimolle in Limpopo.

February 5: Nineteen of the men are arrested at the camp on charges of rendering a foreign military assistance, engaging in mercenary activities and collectively conspiring to commit murder, and are driven to the Pretoria magistrate’s court to be charged.

February 9: Kabila is arrested in Cape Town.

March 22: The 20 men are denied bail.

2014

July 21: The case is sent to the Pretoria high court.

November 28: Fifteen of the accused are released because of insufficient evidence. Kilele, Mukuti, Kazongo and Masikini remain in custody.

November 29: Kabila makes bail but still faces charges.