It’s difficult to trust global financial institutions when scandals about rate fixing and price rigging abound. The latest is the alleged manipulation of the price of platinum and palladium by just four financial companies that reportedly influenced the price of the metals to the detriment of “hundreds, if not thousands” of parties.

Those accused are Standard Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC and BASF Metals.

A class action recently filed in New York by Modern Settings, a jeweller based in the United States, claims the price of both metals has been manipulated, largely downwards, for almost eight years.

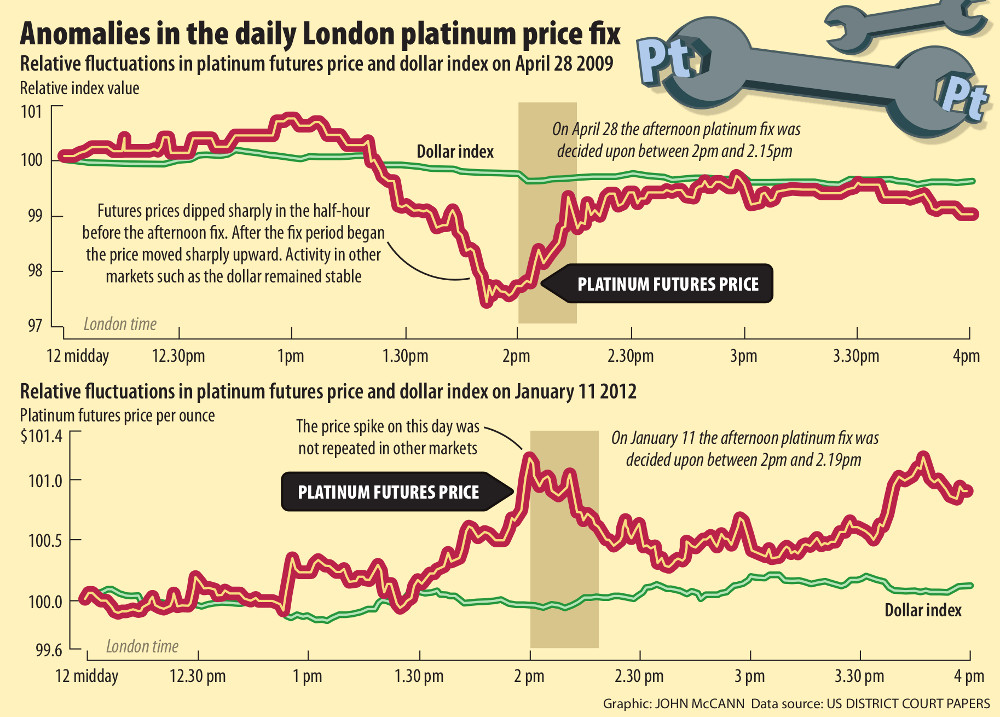

The complaint, of which Mail & Guardian has a copy, is based on a statistical analysis of the platinum and palladium markets, which found unusual price fluctuations before, during and after the afternoon fix for more than seven years, which “can only be explained by [the] defendants’ unlawful manipulation”.

None of the four parties would comment on the allegations.

Some examples in the document show sharp price drops, in some cases as much as $13 an ounce for platinum, during the fixing window, only to rebound shortly afterwards.

In the complaint, Modern Settings says it is seeking relief for the substantial injuries that it and others “similarly situated” have suffered as a result of the accuseds’ “nearly eight-year unlawful conspiracy to manipulate and rig the global benchmarks for physical platinum and palladium prices … as well as the prices of platinum- and palladium-based financial derivative products”.

Latest collusion scandal

This is the latest scandal about collusion linked to major financial institutions, such as the manipulation of the London interbank offered rate in the lead-up to the global financial crisis.

This year, it emerged the gold price had been manipulated by large banks, such as Barclays, which was fined $44-million.

Five major banks were also fined in November for rigging the foreign exchange rates.

Platinum and palladium fixings occur twice a day: at 9.45am and 2pm London time (the latter for the benefit of US trade) and the four defendants are the only participants. The fixings take the form of a simultaneous auction, at which each party, which has calculated its demand for the metals at every possible price, submits this to the chair. The price is then set so that the total demand from the parties perfectly matches the supply. The fixing window is for as long as it takes for the parties to agree on a price, but typically it is just a few minutes.

According to the complaint, before the fix took place, “the defendants and their co-conspirators were privy to, and shared confidential non-public information about client purchase and sale orders that allowed them to glean information about the direction of platinum and palladium prices and, consequently, gave them the ability to execute trades in physical platinum and palladium and platinum- and palladium-based financial products in advance of those movements”.

‘Spoof orders’

Modern Settings also alleges the four parties made large “spoof orders”, which they had no intention of executing, to bait the market to react to what other participants believed were genuine increases or decreases in supply or demand.

This allowed them to reap substantial profits, which injured non-insiders, Modern Settings says in its complaint, adding that this would also have had a substantial effect on the foreign and interstate commerce of the US.

The document states that Standard Bank, HSBC and Goldman Sachs have large commodities desks which offer trading services for these metals. Each also has its own proprietary trading interests in the physical metals, as well as their futures and options for hedging and speculative purposes.

The manipulative conduct can be shown by market analyses, the complaint says, noting that platinum and palladium prices would frequently return to their pre-fixing levels shortly after the fixing meetings.

“[The] plaintiffs’ experts’ statistical analyses have shown these price moves are highly anomalous and suggestive of price artificiality.”

The analyses show that often the price was “driven” downwards and found that between 50% and 65% of the unusual movements were negative during the period concerned. Between 35% and 50% were positive.

Presumably, this was good news for a jeweller but not so for Modern Settings, which in its complaint says: “Plaintiffs and members of the class [action] transacted in physical platinum and palladium and/or platinum- and palladium-based financial products, including platinum and palladium futures and options trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange … [and so] lost tens of thousands of transactions.”

Derivative products

Futures contracts and options are derivative products and, in the cases of platinum and palladium, their prices have a close correlation with the physical metal. Futures contracts are priced as a combination of the immediate metal spot price, plus interest related to financing and storage costs.

The reason to suppress the price, the complaint says, is it “would help platinum futures traders with particularly large short positions in the futures markets because they become more valuable as prices, or future expectation of prices, drop”.

A short position is taken against a stock, commodity or currency in the expectation that it will fall.

The complaint cites research that shows commercial traders of platinum futures, such as the defendants, have held outsized short positions during those seven years.

“In November 2012, the number of ‘commercial’?” short positions was over five times larger than the number of commercial long positions (9 100 long versus 51 400 short), the complaint claims, indicating “ample motive” to suppress the price.

The analysis compares the movements to physical gold, the US dollar index and the MSCI emerging markets index to prove that many cases of sharp price changes in the platinum and palladium afternoon fixing window were not consistent with market behaviour before it.

Futures price dip

On April 28 2009, the futures prices dipped 30 minutes before the fixing, by about $15 an ounce. But once the fixing session started, prices soared almost $20 an ounce and suddenly dropped $7 before the fixing windows closed. Other markets remained stable and thus “discounts the possibility that macroeconomic forces were at play”, the complaint says.

And on November 5 2009, for example, the platinum futures price during the afternoon fix dropped $13, from $1 368 an ounce to $1 355, rebounding to $1 362 little more than an hour afterwards.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers would not disclose the details of the statistical experts.

South Africa’s biggest platinum mining houses declined to comment on the case, although they, too, would presumably have been prejudiced by a metal price manipulated downwards. South Africa produces 70% of the world’s platinum supply.

Although local platinum producers sell more than 95% of the metal directly to their customers on contract, the fix (and usually the afternoon one) has an impact on these negotiations and global market sentiment.

The industry is generally sceptical about the merits of the action.

‘No evidence’

“We have no evidence or reason to believe there has been price manipulation,” said Johan Theron, the spokesperson for Impala Platinum.

“We remain confident that the current price trends are driven by fundamental metal supply and demand balances and other relevant global economic considerations.

“We have taken note of the legal process in North America and will be keenly following any further developments in this regard,” Theron said.

Peter Major, a mining analyst at Cadiz Corporate Solutions, said the market was hard to manipulate given the size of the exchange traded funds and the large stockpiles of the metal in countries such as Russia.

“My experience on the market is that whatever you lose on the price going up you gain on the price going down. I have never seen a trader make money on the regular basis,” he said.

“It’s almost impossible to keep a price where you want it for a few days … you could maybe hold that market a few minutes but it will just bounce back. It’s like a spring.”

Major said to prove that the alleged collusion affected the jeweller and the market was the hard part, not to mention quantifying it.

The complaint seeks the court to certify the lawsuit as a class action, allowing others to join, and to declare that the defendants’ conduct violated the US’s Sherman Act, the Commodity Exchange Act and federal anti-trust laws. It is seeking damages in accordance with such laws, plus interest, although an exact amount has not been specified, and costs.

‘Archaic’ system

But what Modern Settings describes in its complaint as the “archaic” system of fixing, is a thing of the past. The London Platinum and Palladium Fixing Company has handed over the responsibility of administering the fixings to the London Metals Exchange (LME), and an electronic system for fixing platinum and palladium prices was launched on Monday.

(It can be observed live online by going to lmebullion.com at 9.45am or 2pm London time.)

The LME told the M&G it required participants to comply with price-discovery regulations, which included a disciplinary procedure that allowed it to impose a wide range of sanctions, including fines.

“The LME will adopt the same rigour in delivering the London platinum and palladium prices as with its current market, which means there will be fully auditable and transparent price formation made possible through our existing robust compliance and regulatory framework,” it said.

In a previous version of this article it was stated that: Futures contract prices are what the market believes will be the spot prices of physical platinum or palladium on the delivery dates specified in the futures contracts, when in fact, Futures contracts are priced as a combination of the immediate metal spot price, plus interest related to financing and storage costs.