Colour coded: Daniel Naudé's Satin Bower 4

Ponder on colour is the challenge of Chroma, the summer group show of the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. The title, which refers to the intensity of colour, is taken from filmmaker Derek Jarman’s book, Chroma: A Book of Colour.

According to the gallery’s explanation, the exhibition “presents both works that see colour as their leitmotif and others that, often with new strategies, reflect on the politics of colour in recent years”.

Artistic expression speaks to us through our senses. That is, we react to it on the basis of our sensory experience. And, in all the battles for the soul of the sensible, colour, as the Russian painter and art theoretician Kazimir Malevich argued, isn’t just an end in itself but “must be given life and right to individual existence”. That’s to say the constitutive elements of painting such as colour, texture and composition aren’t secondary to the content, as is generally argued.

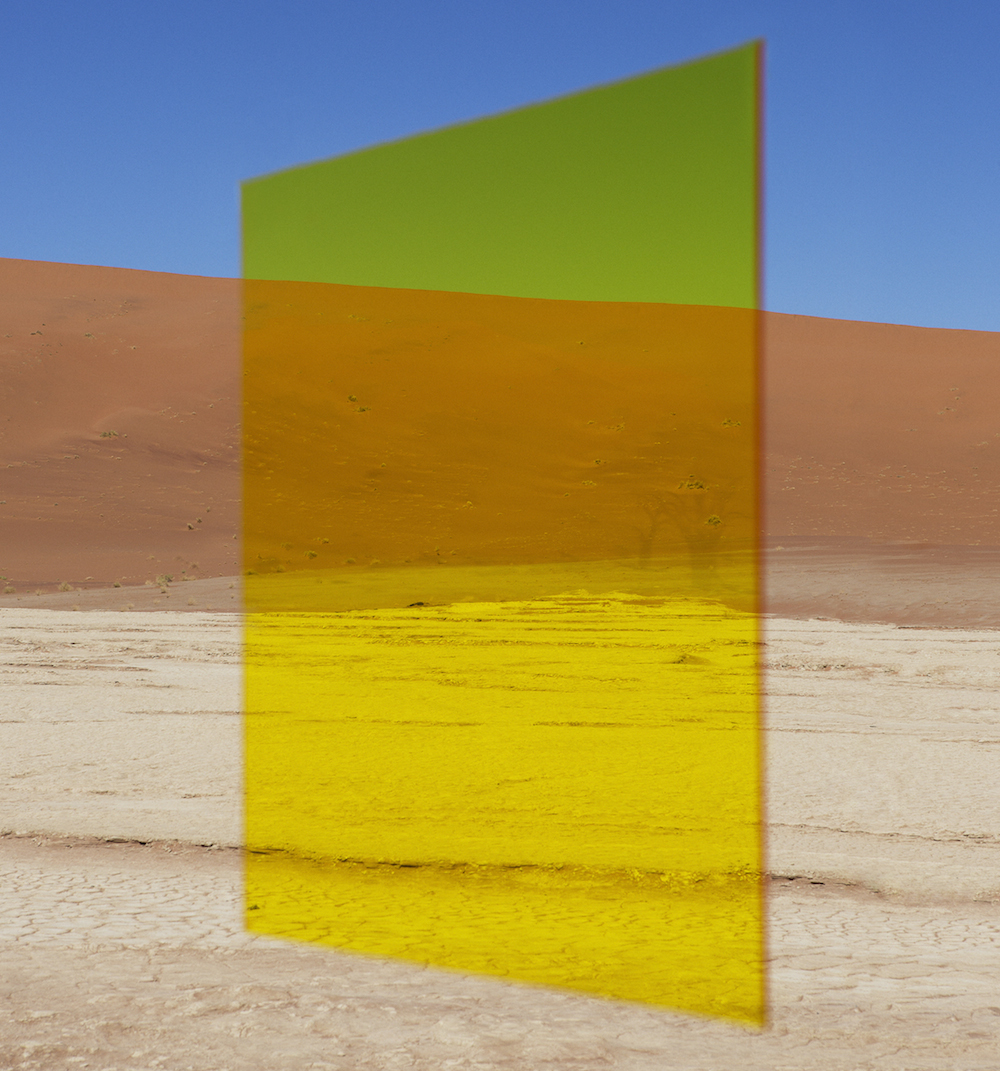

Yellow Vlei, Viviane Sassen

In Chroma, adding a significant detail such as the blue in Daniel Naudé’s Satin Power series raises a question about its significance. In other works, such as those of Donald Odita, Moshekwa Langa and Viviane Sassen, there’s a direct investment in colour.

It seems colour must obliterate all to exist, asserting itself in the most vivid and glaring manner, weighed against content and form so as to emerge as both object and subject.

Similarly, in the relatively monochomatic works of Bruno Boudjelal, Nicholas Hlobo, Estevão Mucavele and Deborah Poynton, this obliterative gesture – though not as imperious, but subtle – exists. In Boudjelal’s and Poynton’s work, the white and the green that swallows the background detail requires us to strain our eyes in order to perceive it. But in Hlobo’s and Mucavele’s work, there is sensitivity, charm and stillness, and a controlled sense that keeps drawing us in.

Malevich once said of colour: “The subject will always kill colour and we shall not notice it. Then, when the faces painted green and red to a certain extent kill the subject, the colour is more noticeable.”

This reminds me that the debate between content and form is old, and about how it plays itself out today.

This potential vengeance of colour becomes rather interesting when read in the context of race. Chroma presents us not only with formalist tensions but also with parallels and crossovers between colour in artistic form and the uses of colour in the social field.

In European art history, the assertiveness of colour insisted on by the likes of Malevich and others has a specific dynamic. But when the abstraction of colour becomes part of the vocabulary of society’s designatory machine, it takes on a “new guise”, as Frantz Fanon would say. It possesses the same lethal power it uses to erase content.

In the popular narratives told about modernity and colonial imperialism, we often refer to the Bible and the gun. We often omit the story of the violence of the paint tube, the camera and the pen – or that artistic representation was inseparable from the context of its emergence.

With all the weight colour has on South African life, walking through Chroma was like a reality extracted from Mars. Though sufficiently suggestive, we are never too certain about its direction, and we are not able to follow it. As is almost too typical of the workplace’s end-of-year functions, at most, it seems Stevenson just threw a “jol” for its “stuff” and dubbed it “chroma”.

Harbinger with Rainbow, Jane Alexander

This is not an attempt to overlook the significant role colour plays in the formal and aesthetic representation and construction of South African art. But the space given to abstract ideas of colour, compared with works such as the Colour Me series by Berni Searle, Jane Alexander’s Harbinger with Rainbow and Mawande ka Zenzile’s paintings, leaves much to be desired. This is typical of the general indifference to sociopolitical reality, if not impatience with the race question, that continues to structure every perceptive reach of our society.

Beneath the illusory motif of the rainbow, which apparently has “allowed more spacious considerations of the experiences of colour in art”, there lurks the invisible nightmare of racial blackness.

In Chroma, aggressive colour is mobilised to its full kaleidoscopic potential, as the aesthetic counterpart of political omission. We must insist that, though there is a litany of colour that pops up in our ordinary lives, the black and white reality seems to be the only palette that structures those lives.