Hammarskjöld's body

It has been more than half a century since the plane carrying United Nations secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld crashed en route from Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) in the Congo to Ndola in the then Northern Rhodesia. The sole survivor died within a few days.

Hammarskjöld was due to meet Moïse Tshombe, leader of the resource-rich Katanga province, which had broken away from the Congo at the height of the cold war and African decolonisation.

Hammarskjöld, who was committed to Congolese sovereignty, was regarded with intense suspicion by powerful political and economic interests in the West who backed Tshombe. There was little love lost in some quarters for the UN, some of whose personnel were assassination targets. On September 18 1961, the day Hammarskjöld died, the UN headquarters in Elisabethville (today known as Lubumbashi) were strafed.

The crash occurred at night on an eastward approach to Ndola airport: the Swedish-crewed Douglas DC-6B (known as the Albertina), landing gear down and still under power, hit the ground in thick woodland and broke up.

The 1962 UN inquiry reached an open verdict, as had an initial accident investigation. A Rhodesian inquiry blamed pilot error, although the postmortem report noted gunshot wounds on some bodies – possibly the result of exploding ammunition, although the armed bodyguards were not affected. The remains of the plane were buried, the full autopsy records are nowhere to be found and the official site photographs of the bodies (if they still exist) are in private hands.

And the passing of years has not erased questions that have no plausible answers.

The pilot, then on a westerly course, reported sighting the airport lights at Ndola and was spotted from the ground by assistant police inspector Adrian Begg, who was on security duty. But the plane then disappeared. Police officer Marius van Wyk reported to Begg the sighting of a flash in the sky to the west. This was relayed to the airport manager but inexplicably, the airport was then closed on the extraordinary assumption (by British high commissioner Lord Alport, among others) that Hammarskjöld’s plane had diverted elsewhere. There was no electronic recording from air traffic control, only retrospective notes that appear incomplete.

The wreck was found the following afternoon just 15km (and two minutes’ flying time) from Ndola airport, confirming Van Wyk’s earlier report, although the search at daylight had set off in other directions and failed to use all 18 aircraft at the disposal of the authorities. Charcoal burners in Twapia, under the airport flight path, had noticed another aircraft in the sky and claimed sighting flames and an explosion.

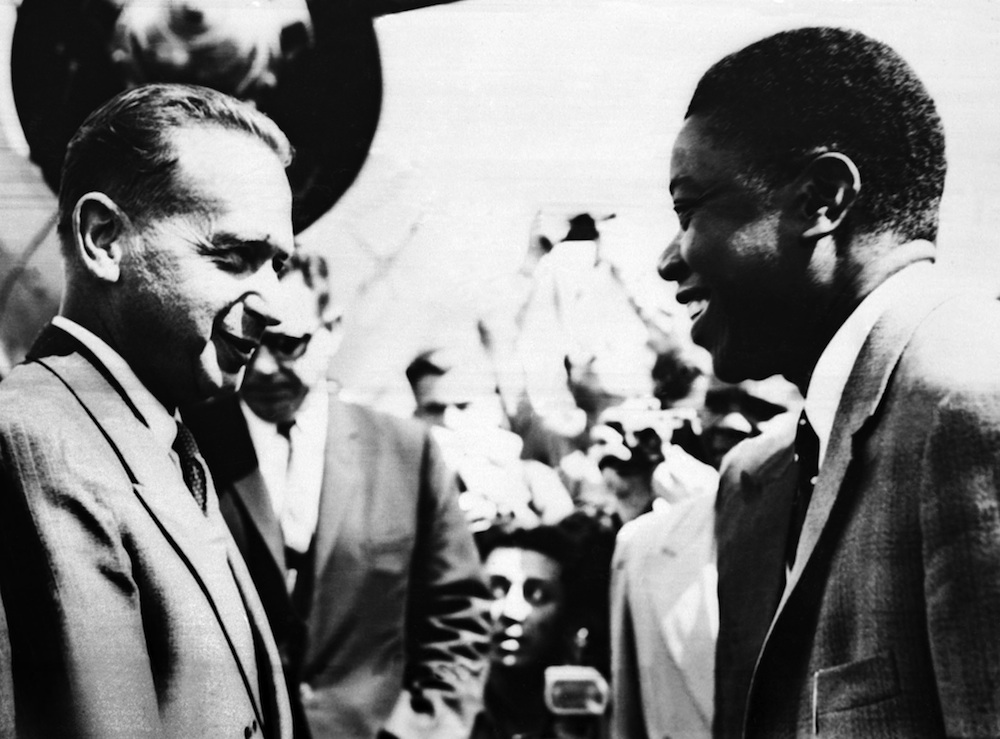

UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld (left) was due to meet Katanga leader Moïse Tshombe when he died in a plane crash. Hammarskjöld’s drive for Congolese sovereignty did not endear him to the West. (Robin Barnes)

Nearly 50 years later, University of London academic Susan Williams, author of the recent book Who Killed Dag Hammarskjöld?, interviewed a former employee of the American National Security Agency based in Nicosia who clearly recalls monitoring wireless traffic that night, possibly in French, from a pilot apparently engaged in an aerial attack.

Then there was the crash site itself, which is where answers, if they are to be found, must lie. Northern News reporter Marta Paynter recorded that Hammarskjöld’s body, resting against an ant hill, was the only one not burned – and may have had a bullet wound to the head airbrushed out of autopsy photographs. His briefcase and cipher machine were recovered. Locals believed the site had been visited before the authorities and members of the press reached it 15 hours after the crash.

This was verified by a motorcyclist from the mining town of Bancroft (today Chililabombwe). Wren Mast-Ingle, who heard the Albertina aircraft come down, investigated and was ordered away from the site by half a dozen men in Jeeps and dressed in paramilitary uniforms. However, he got as close as 20m and remembers seeing “fist-sized holes” in the fuselage, which was not burning at that stage.

Later, according to South African writer Arthur Gavshon, it was subjected to intense heat that reduced it to 20% of its mass and the corpses to the size of children. Who were the paramilitary figures? British colonial police used Landrovers, but Rhodesian Light Infantry troops were accused by the UN’s man in Elisabethville, Conor Cruise O’Brien, of wearing Congolese gendarmerie uniforms. Gavshon believed that Northern Rhodesian territory accessed by back roads was freely used by mercenaries.

There are numerous theories for the crash, from a remotely triggered bomb planted before take-off to a failed hijacking. The secessionist state of Katanga, described by O’Brien as a “sinister farce”, had strong mercenary support including a small air force. Ndola was within easy reach of the highly porous Katanga border.

The Albertina plane could have been shot down by Katanga’s one operational Fouga fighter using a makeshift landing strip, or even bombed from a modified Dove aircraft. The possibility of a French speaker in the cockpit reinforces the idea of a failed attempt to divert the plane, and prior knowledge of such a plan could explain the closure of Ndola airport. O’Brien was convinced that there was aerial intervention of some sort and Albertina’s circuitous flight path, hugging Lake Tanganyika, was designed to stay out of range of hostile aircraft.

A case of conspiracy will be even harder to prove than the shooting down of Albertina. Intriguingly, there is a South African connection, possibly forged, that emerged from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. The apparent evidence of sabotage appeared, strangely enough, in a file on the assassination of Chris Hani. The department of justice is now unable to produce the originals.

The death of the world’s most important diplomat in questionable circumstances was relegated suspiciously quickly to cold-case status and a historical footnote. That changed, however, with the presentation at The Hague on September 9 2013 of the findings of the four jurists (one of them Richard Goldstone) of the Hammarskjöld commission. They found that in spite of the complexity of the case, there is a “golden thread”: persuasive evidence that Hammarskjöld’s plane was subject to hostile action, with further questions raised about what exactly happened on the ground before the wreck was officially located.

UN resolution 1759 of October 26 1962 allowed the possibility of another inquiry should new evidence come to light. The UN general assembly, at its meeting of December 15 2014, considered a Swedish proposal for a “phased resumption” of the inquiry, including access to hitherto classified documents, and this now awaits budgetary approval. Should it go ahead, there could soon be a radical revision of mid-20th century Central African and cold war history.

Christopher Merrett is a freelance journalist