Eminem.

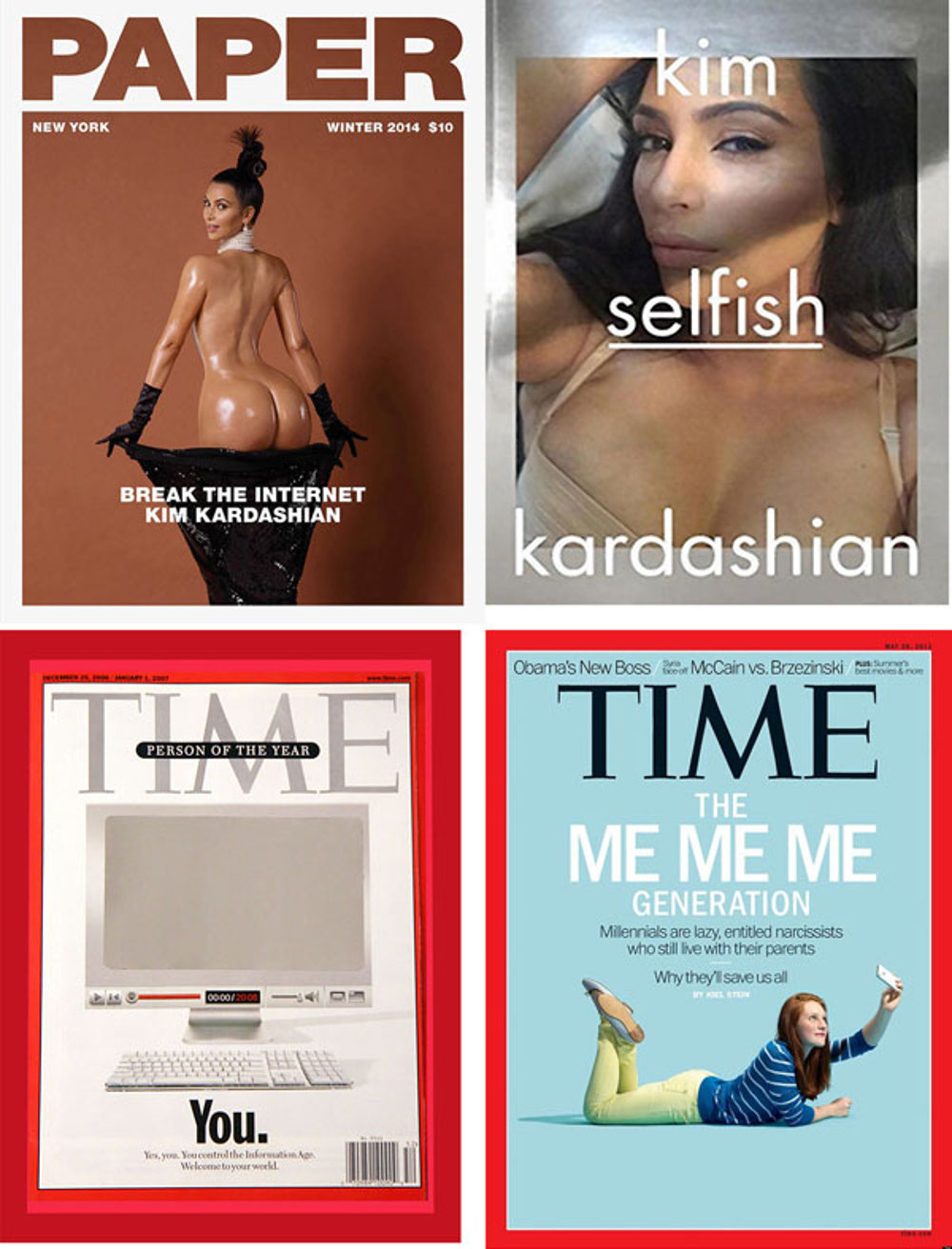

Sultry and pouting, Kim Kardashian lies in bed, her ample cleavage almost spilling out of her low-cut flesh-coloured bustier. She stares seductively at the camera, one side of her face framed by her arm in a trademark selfie pose. Scroll down for more glorifying self-portraits of the reality television star with her ripped abs, voluptuous butt and pneumatic bosoms.

Welcome to the online teaser for Selfish, the aptly titled 352-page hardcover book featuring nothing but self-taken snaps of the undisputed “queen of selfies”, due for release early next year.

As one of the world’s biggest celebrities, who has built a multimillion-dollar fortune out of the business of famous for being famous with a legion of adoring fans (25.6-million on Twitter at the last count) – Kardashian may be at the extreme end of society’s narcissistic, self-loving spectrum, but no one can deny she is a symbol of our society reflected back at us.

It’s all about Me, where we’ve come to believe everything we say, do and think is fascinating and must be shared. And thanks to enabling technology and social networking, we can be heard further, louder and by more people than ever before.

Across the globe, every age, profession and class has become obsessed with exposing and promoting ourselves digitally, in every gory detail. We live out loud 24/7, share the minutiae of our daily lives on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram – look what I ate for breakfast/the cake I baked/my new nail polish! – and upload puerile clips of our snoring cat on YouTube, share endless selfies and shamelessly hang out our private lives for scrutiny.

The point of it all

Whether we have anything interesting to say is hardly the point. In 1968 Andy Warhol wrote in the programme for an exhibition of his work at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, that “in the future, every-one will be world-famous for 15 minutes”. He was referring to the fleeting nature of celebrity, a sentiment reportedly triggered by a 1965 outdoor photoshoot during which bystanders tried to push into the shot with him. Little did the pop artist know how prescient and far-reaching his remark would be.

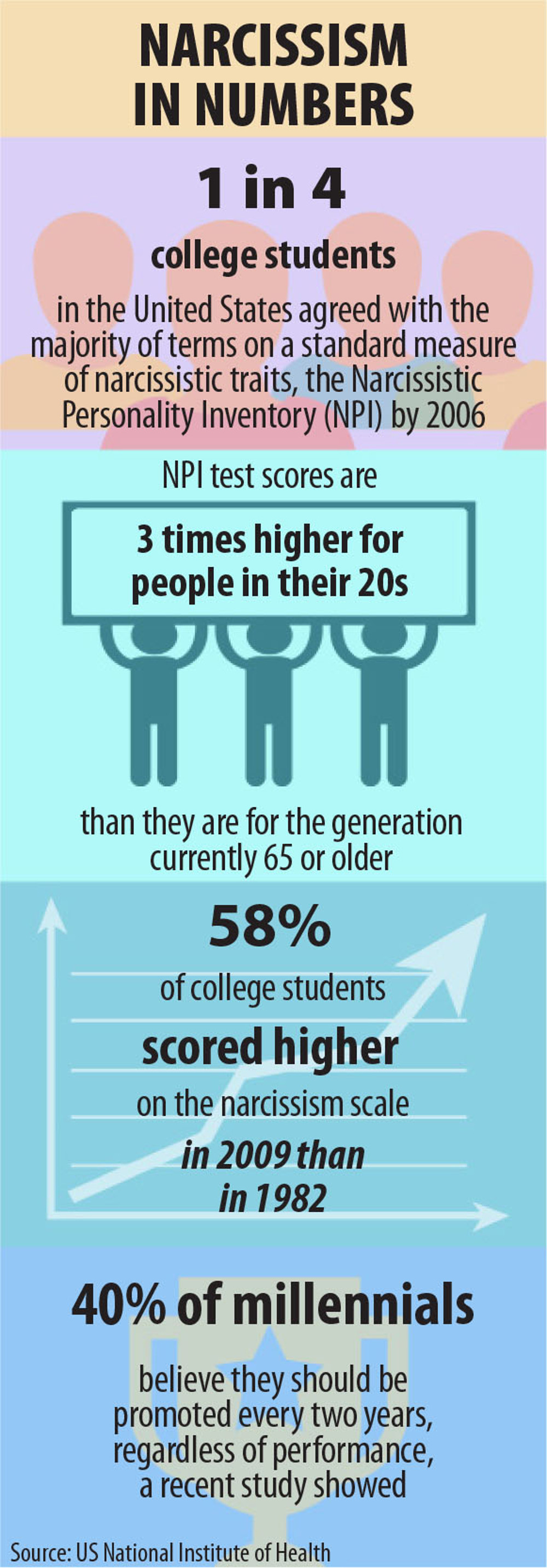

We’ve become steadily more narcissistic over the past few decades, but the social media explosion has blasted us into another orbit. The post-2004 internet with its spike in user-focused sites has created a perfect storm for an I-based culture, one in which instant fame is almost within our reach and how we look and what we present to the world trumps who we really are.

“Social networking, and the internet as a whole, seems to have simply landed in an extremely fertile place at an extremely fertile time in history, when we all have these narcissistic tendencies anyway,” says Jeffrey Kluger, Time magazine editor-at-large and author of a new book on the subject, The Narcissist Next Door.

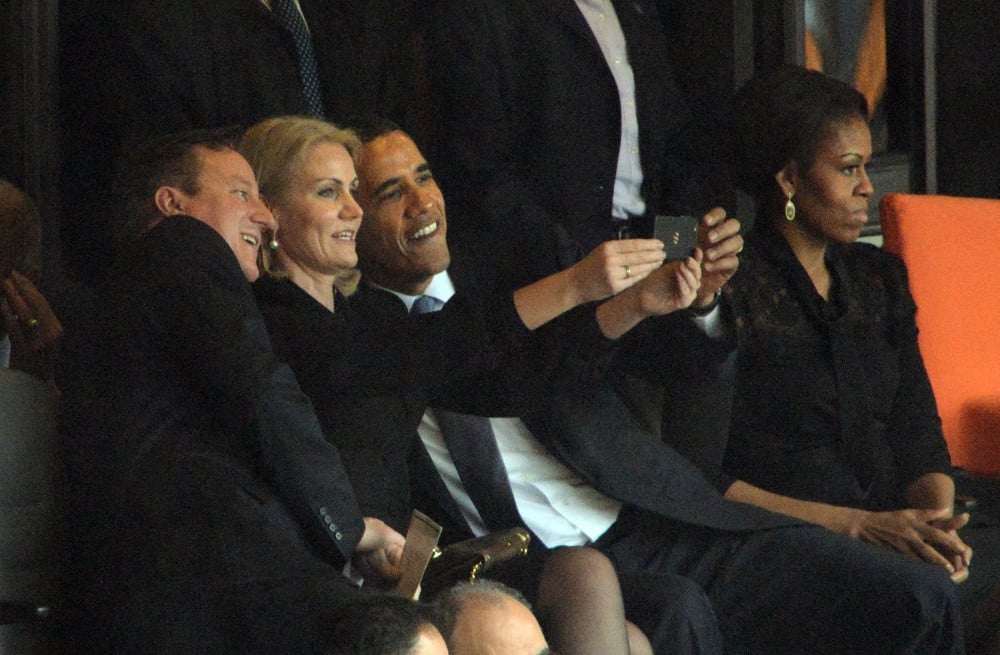

British Prime Minister David Cameron, Denmark Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt and US President Barack Obama at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service. (Roberto Schmidt, AFP)

In December 2006, Time made “you” their person of the year for promoting Web 2.0. The cover came with a mirror, allowing us to look at ourselves and ponder our own role in creating this new world order, in which we set the agenda by sharing, posting, liking, blogging and tagging. Fast forward to 2013 and the magazine’s cover story on “lazy, entitled millennials” (those born between 1980 and 2000), flaying today’s generation of youngsters and, like many pop-culture analysts and academics, branding them “entitled, arrogant, spoiled and preening”. Their poster child: a teenage girl snapping a selfie.

Social media comes in for a lot of flak from these commentators, with many squarely blaming it for fuelling this era of public self-glorification. And they seem to have empirical support. In the past few years, a plethora of research has been pouring in that makes connections between Facebook, Twitter and narcissism. The main problem is, of course, that they help to reinforce the idea that what matters most in this world is how things, and people, look.

Interaction

Laura Buffardi, a postdoctoral researcher at the Universidad de Deusto in Bilbao, Spain, says that “narcissists use Facebook and other social networking sites because they believe others are interested in what they’re doing, and they want others to know what they are doing”.

This does not create the environment for real relationships, says Cape Town psychologist Dr Janne Dannerup. “Social media causes users to overemphasise their public persona – how they come across in society – while paying too little attention to building and nurturing close personal relationships.

“Since people put themselves out there through social media and pay overwhelming attention to their exterior appearance – with the ‘right’ clothes, car, smartphone or home – there is an expectation of acceptance, closeness and intimacy with a great number of people that isn’t borne out by reality,” says Dannerup.

The worrying implication for society is that narcissism reinforces itself in an endless loop, as social media users are likely to be connected to those who are more narcissistic than the average person. “Social media sites therefore also shape the norm of behaviour,” points out Keith Campbell, a professor of psychology at the University of Georgia, United States, and co-author with Jean M Twenge of The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement.

But it’s not just about skewed relationships. There are darker implications.

Aggressive narcissists

Narcissists are aggressive when they have been insulted or threatened, says Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State University and lead author of a report titled Egos Inflating over Time.

“They tend to have problems with impulse control, so that means they’re more likely to, for example, be pathological gamblers [or] commit white-collar crimes.”

The ample research on our narcissistic age and its causes has opened up a deluge of books, blogs, feature and op-ed articles on the topic. Google “narcissism” and it’ll throw up a long list of literature, covering every angle of the topic in exhaustive detail. Try these for size: Disarming the Narcissist: Surviving and Thriving with the Self-Absorbed; Why is it Always About You?: The Seven Deadly Sins of Narcissism; Narcissism: Surviving the Self-Involved – A Little Primer on Narcissism and Self-Care; The Object of My Affection is in My Reflection: Coping with Narcissists; Narcissism: Denial of the True Self and so on, and so on.

Kim Kardashian’s internet-breaking cover for ‘Paper’ magazine and her aptly titled book, ‘You’ was ‘Time’ magazine’s person of the year in 2006 and in 2013 the magazine featured the ‘me, me, me’ generation of millenials.

Every major media outlet, from the lowbrow to the highbrow, has given it the once-over. And although commentators debate degrees of severity on the spectrum and its negative implications, none denies the existence of this psychocultural phenomenon. The worry seems to be that, although the numbers of clinical diagnoses have risen, it’s the presence of narcissistic personality traits among “normal people” that is seen to be potentially more harmful, as it is so much more common.

Which is not to say that narcissism is always a bad thing. Kluger believes that the right amount of narcissism can be “bracing and, indeed, essential to succeeding – at least if you plan to succeed in a big way”. But when confidence becomes overconfidence (and is not grounded in reality) and self-esteem becomes about being better than others and not equal to others, it becomes problematic. Kluger refers to it as a certain “coarsening and heedlessness” to the needs of the people around you in favour of your own.

Think you may be a culprit?

Narcissistic behaviour

Behavioural traits of narcissism include an inflated view of oneself, a sense of entitlement, attention seeking and a willingness to exploit other people. Add to this a preoccupation with fantasies about success, power or beauty, having an exaggerated sense of self-importance or behaving in an arrogant or haughty manner.

When it reaches extreme proportions, it moves into the realm of narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) [see “When self-love becomes bad for your health”].

Misguided parenting techniques are considered one of the drivers of entitlement. There’s a new breed of “special” children, for whom healthy competition, which teaches children those all-important lessons and values of hard work, failure and resilience, is eschewed for ego stroking, confidence boosting and a situation where everyone’s a winner – lest the little prince or princess feels disappointed and inept.

Danny Bowman, Britain’s first ‘selfie addict’.

“It’s a backlash,” says Johannesburg clinical psychologist Dr Louise Olivier. “Because the parents’ parents didn’t shower them with enough attention and material possessions, they’re overcompensating now,” she says. “The new generation is so indulged that they’ve developed this sense of entitlement – believing they deserve things without having to work for them – and the belief that everything must revolve around them.”

A lack of empathy is another key trait of narcissistic behaviour and research bears out the worrying fact that empathy levels have been declining over the past 30 years, with an especially steep drop since the new millennium dawned.

Selfie storm

According to a major 2010 study into empathy among US students, researchers at the University of Michigan’s institute for social research found that today’s students are generally less likely to describe themselves as “soft-hearted” or to have “tender, concerned feelings” for others. They are more likely, meanwhile, to admit that “other people’s misfortunes” usually don’t disturb them. In other words, they might be constantly aware of their friends’ whereabouts, but all that connectedness doesn’t seem to translate into genuine concern for the world and one another.

Of course, we don’t have to look further than our cellphones to see what the researchers are already telling us. The Oxford Dictionary made “selfie” its word of the year in 2013 for good reason. We’re living in a selfie storm, pushing narcissism and our obsession with looks up a notch. Now we’re not just content to document everything in our lives, we also have to include our faces in the photos.

Miley Cyrus has posted the most selfies on Twitter and Instagram.

Case in point: US President Barack Obama huddles up to British Prime Minister David Cameron and Denmark’s prime minister, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service before Thorning-Schmidt, like a naughty schoolgirl, snaps a selfie of the trio. Ellen DeGeneres creates arguably the most memorable moment in Oscar history when her multicelebrity selfie with Bradley Cooper, Brad Pitt and Julia Roberts broke the record for the most retweets. Selfie queen Miley Cyrus holds the dubious honour of having posted the most self-photos on Twitter and Instagram, while Justin Bieber, a trailblazer in the celebrity selfie obsession, invested in Shots last year – a social networking app exclusively for selfies.

Closer to home, Bonang Matheba splashed photos of herself draped over a luxury yacht on Instagram, while model Lee-Ann Liebenberg took to her Instagram account to show off no-expense-spared Frozen-themed party for her four-year-old’s birthday party.

Mental health problems

A staggering 91% of US teens have posted a picture of themselves online, and psychiatrists are starting to link the growing selfies trend with mental health conditions that focus on a person’s obsession with looks.

Take 19-year-old Danny Bowman. Dubbed Britain’s first selfie addict, he first started posting selfies on Facebook at age 15. After receiving online comments about his face, he became obsessed with looking perfect and his selfie addiction spiralled out of control.

Bonang Matheba splashed photos of herself draped over a luxury yacht on Instagram.

Bowman would routinely spend 10 hours a day taking up to 200 snaps of himself on his iPhone. He became so obsessed with taking “the perfect selfie” that he tried to kill himself when his efforts failed. This was after he dropped out of school, remained housebound for six months and lost dramatic amounts of weight in his attempt to capture the perfect self-portrait.

“It quickly started to control my life,” Bowman said in an interview with the United Kingdom’s Telegraph. “It was all I thought about from the moment I woke up in the morning to when I fell asleep at night. I didn’t want to set foot in the outside world because I thought people would be repulsed by the sight of me.”

British psychiatrist Dr David Veal told the International Business Times that “two out of three of all the patients who come to see me with body dysmorphic disorder since the rise of camera phones have a compulsion to repeatedly take selfies”.

Despite incontrovertible evidence that Westernised, middle-class societies have become more narcissistic – significantly stoked by social media – it’s not all doom and gloom.

Reversing trends

In a landmark study published late last year, Twenge found that younger millennials who came of age during the global economic crisis started reporting more concern for others and less interest in material goods. Although concern for others had been decreasing among high school seniors and some symbols of materialism – such as expensive cars – had been increasing for nearly four decades, these trends began to reverse after 2008.

This echoes the findings of a recent survey by the Pew Research Centre, a think-tank based in Washington, DC, in which more than half of the millennials polled said they would take a 15% pay cut to work for a “meaningful organisation”.

Justin Bieber has invested in Shots, a social networking app exclusively for selfies.

No South Africa-specific studies into the prevalence of narcissism have been done. To some degree we are lagging as an adopter of these values, says Leonard Carr, the Johannesburg psychologist who labelled Oscar Pistorius a “classic narcissist” during his murder trial.

In the workplace, for example, Carr has noticed a less calculating and cut-throat corporate culture than any of the extremes he witnessed during his work in US boardrooms. Although we may mimic their culture in many ways, “we are far behind”, he says.

Buffers against narcissism

Campbell believes some cultures have buffers against narcissism.

“South Africa has the philosophy of ubuntu [literally, we are who we are because of each other], while Australia has the tall poppy syndrome [a tendency to cut achievers down to size],” he told the Mail & Guardian in an email interview.

In his book, Campbell refers to countries such as India as having a natural resistance to narcissism, given their collective cultural values that emphasise cohesion, rules and family structures.

Johannesburg’s Olivier takes solace in the inevitable “pendulum swing” against negative behaviour and points, for example, to the teaching of life skills in South African school curriculums, advocating concepts such as kindness and sharing.

But a societal mind shift has to take place. And it can, says Time‘s Kluger.

“But slowly … and it will only gather momentum if narcissism is met with social opprobrium. As long as posting and tweeting and posing and preening continue to be rewarded, we’ll continue to indulge. The more these things fall out of fashion, the more people will curb their behaviour.”

Right now, though, it seems we’re a long way off from curbing our enthusiasm for chronic self-involvement.

Tracy Melass is a Cape Town-based freelance editor and writer.

You probably think this test is about you

It’s easier than ever before to diagnose a narcissist, suggests a new study published in Plos One, an open-access peer-reviewed journal published by the Public Library of Science. All you have to do is ask.

The reason narcissists are so honest is because they don’t think their narcissism is a problem, which is consistent with people who think so highly of themselves.

Narcissism has traditionally been diagnosed with a 40-item questionnaire known as the narcissistic personality inventory (NPI) – you can take the quiz online at Psychcentral.com or on Time magazine’s website. The lowest you can score on the NPI is zero; the highest is 40. The average score in the United States is between 15 and 16, depending on age, gender and other variables.

But a team headed by psychologist Sara Konrath of the University of Michigan suspected that in some cases it might be possible to achieve the same result by asking just one carefully phrased written question: “To what extent do you agree with this statement: ‘I am a narcissist.’ (Note: The word ‘narcissist’ means egotistical, self-focused and vain.)”

They were then asked to rate how true this statement was of them on a scale of one to seven.

To a statistically significant extent, the scores on this single-item scale correlated with the subjects’ scores on the more complex NPI.

When self-love becomes bad for your health

When narcissism gets serious, it could result in a medical condition known as narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). This is a mental disorder in which people have an inflated sense of their own importance and a deep need for admiration.

They feel they’re superior to others and have little regard for other people’s feelings. But behind this mask of ultra-confidence lies a fragile self-esteem, vulnerable to the slightest criticism.

NPD is typically diagnosed and treated by a mental health professional such as a psychologist or psychiatrist. The person will typically be asked a series of questions from a standardised questionnaire or be given a self-test to help to assess the presence of an illness.

In general, a person with a personality disorder doesn’t seek out treatment until the condition in question starts to affect their life significantly.

This most often happens when their coping resources are stretched too thin to deal with stress or other life events.

NPD treatment is centred on psychotherapy. There are no medications specifically used to treat this disorder.

But if you have symptoms of depression, anxiety or other conditions, antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications may be helpful. Source: The Mayo Clinic