‘The doctor told me that she had a heart condition,” Santie Coetzee* said. Her voice was barely audible. She tightened her grip on the crumpled tissues in her hands as she recalled the day her youngest child was born.

The condition, doctors told her, was exacerbated by the circumstances of the birth.

Six months ago the 43-year-old Coetzee gave birth to the baby girl in her home in the Central Karoo town of Beaufort West in the Western Cape. The infant, who was breech (born buttocks or feet first instead of the normal head-first position), was also premature and weighed a mere 1.72kg – nearly half the weight of a fully developed baby at birth.

Risky choices

Melissa Morris*, a nurse at the local clinic, said because Coetzee did not visit the clinic during her pregnancy, she jeopardised her own health as well as her baby’s.

“If she had visited the clinic we would have seen the baby’s position sooner and scheduled her for a Caesarean section instead of her delivering at home,” Morris explained.

“That’s what he [the doctor] said to me,” Coetzee said. “As a result, we have to see the [paediatrician] every month.” But a heart condition is just the beginning of her baby’s health problems. Like her five older siblings, the infant also has fetal alcohol syndrome.

Fetal alcohol syndrome is the most severe form of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and the “most common preventable form of mental disability in the world”, according to the Foundation for Alcohol Related Research (Farr).

Women who, like Coetzee, drink alcohol during pregnancy risk causing irreversible damage to their unborn babies’ brain and other organs. The organisation says there is no known safe amount of alcohol pregnant women can drink without increasing the risk of damaging their unborn babies.

Widespread problem

“I handle a lot of cases of children with fetal alcohol syndrome. I can’t even count how many. It’s terrible; most of the children [born at the clinic] have the condition,” said Morris. “I’ve been doing this job for 18 years and we are seeing more and more children with fetal alcohol syndrome.”

According to a 2013 South African Medical Journal study, the condition is endemic in impoverished communities of the Western and the Northern Cape.

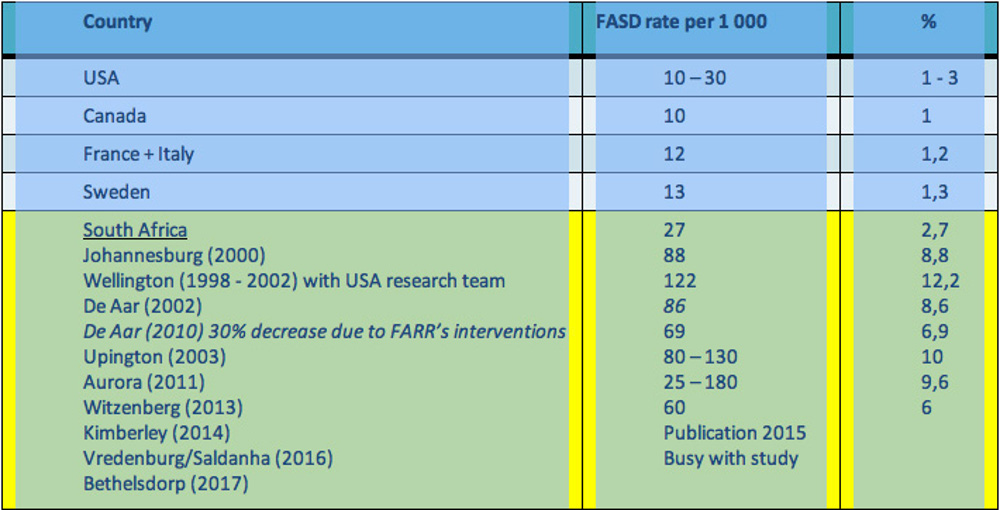

The study found that 20% of women in the Western Cape drink heavily during pregnancy. The prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder has been well researched in the Western Cape. However, studies in the Northern Cape and Gauteng have also shown high prevalence rates [see table]. Farr is exploring prevalence in the Eastern Cape, where it also seems high.

Prevalence rates in the other provinces are unknown, according to Sithembiso Magubane, of the Western Cape health department.

“It is important to note that the research has proven that fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is not limited to wine farms or rural areas. A recent study in Kimberley showed that in some residential areas the prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is as high as 11%.”

Public health problem

The syndrome is “a serious public health problem” and health professionals are not sufficiently trained and supported to identify and manage the condition, according to the department.

“If the family continues to abuse alcohol it often affects their co-operation with healthcare programmes. Children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have learning and behavioural difficulties and the clinics are often the first resource for seeking assistance,” said Magubane.

One of the families in Morris’s caseload is Coetzee and her children. This, Morris said, has been one of the most challenging cases.

Despite having six children, Coetzee has never attended antenatal checkups and is reluctant to bring her children in for appointments because she is “afraid of being scolded by the nurses at the clinic”.

“I am the nurse looking after all her children. I have to check up regularly and if there is a problem I must be firm. So she didn’t want me to know that she was pregnant because we did speak about prevention. So when she found out she was pregnant she didn’t come to the clinic at all. With her last pregnancy I sent her messages regularly to come to the clinic, but she never came,” said Morris.

After learning about her daughter’s condition, Coetzee said she regrets not listening: “If I had gone to the clinic things would have turned out differently.”

No change

But her moment of clarity was short-lived. Little has changed since Bhekisisa first spoke to Coetzee and Morris six months ago. “It is not going well,” Morris said in a recent telephone interview.

Morris had to involve social workers when Coetzee failed to bring her last-born to the clinic for an appointment with a doctor late last year.

“The other day we had to refer the baby to the hospital. Coetzee hasn’t been coming to her appointments at the clinic for a while. Last week I had to call in a social worker to get Coetzee to take the baby to the hospital. The second-youngest child, who is four years old, also has to be hospitalised,” said Morris.

Coetzee’s youngest child, who is now 11 months old, has been admitted to hospital a number of times over the past few months for severe malnutrition.

“We are worried about all those children. The second-youngest will be hospitalised this afternoon – also with severe malnutrition.”

Dire consequences

According to Magubane, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is “associated with low birth weight and babies struggle to gain weight and thrive. For this reason, many of them have to be supported on the health department’s nutritional programme. They have a compromised immune system, leading to an increase in childhood illnesses.”

Part of Morris’s duties involves weighing children, taking measurements and placing them on a feeding scheme if necessary.

“We then refer them to the social security agency so that they can get food parcels. But some of the parcels the children never get because they get sold for alcohol.”

Many parents do receive the child support grants but “they misuse the money”, said Morris.

“They spend the money on alcohol. So we have a terrible situation. We can almost not handle them. We had a terrible time over the festive season with an increased number of children being hospitalised.”

Associated factors

Factors such as poverty and the presence of a drinking partner are risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

“Hopelessness and low self-esteem, associated with poverty, all lead to increased alcohol use,” said Magubane. “Research has found that pregnant women do not normally drink alone, but drink in a social context. Therefore it is important that partners are involved in the prevention of the condition.”

*Names have been changed because interviewees fear victimisation