Uncut diamonds seen through a jeweller's loupe. Zimbabwe may not hire Global Diamond Tenders in future

ANALYSIS

For the diamond-cutting industry in Botswana, the news last week could hardly have been much worse. In January, the press reported that diamond cutters MotiGanz and Leo Schachter had laid off 150 workers. Then last week a bombshell was dropped – the Teemane Manufacturing Company, owned by Diarough, would close, with the loss of about 320 jobs in Serowe.

It is the biggest employer in the village and the consequences will be felt for years to come – about 2 000 people are dependents of those employed in the industry. With a total reported employment in the diamond cutting and polishing industry of 3 750 in 2014, this is a massive retrenchment.

In 2013, Botswana is reported to have exported polished diamonds worth 6.6-billion pula (R7.9-billion).

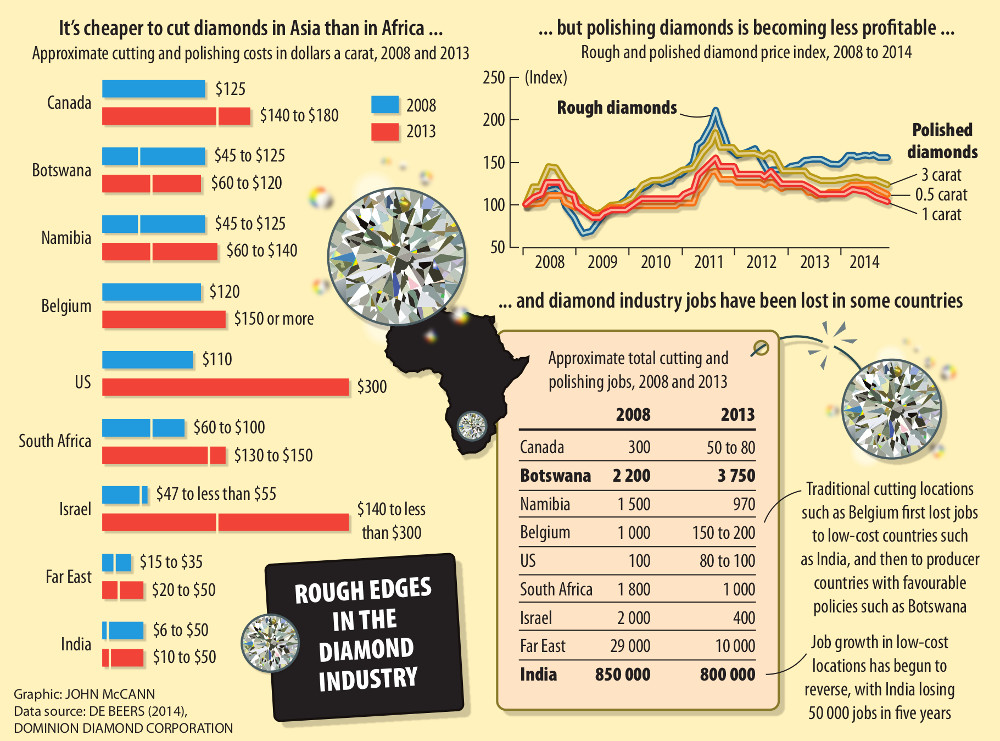

Two reasons are usually given for the closures in Botswana’s diamond sector. The first is structural – Botswana, like Namibia and South Africa, cannot compete with the low-cost and high-productivity places such as Surat and Mumbai in India, where most of the world’s diamonds are cut.

The second is squeezed margins. Wages in Botswana are about the same as they are in India but the differences are in productivity. Indian cutters will produce two to three times as much as those in Botswana. This is not new – it was known before the establishment of the industry in the 1990s.

The table shows the costs of cutting and polishing a rough diamond in various places. Botswana has become more competitive but it cannot compete with India, although it is more competitive than either South Africa or Namibia.

Despite the growth in employment in Botswana over the past few years, the diamond finishing industry is now “going south”.

But what has changed to make it necessary to close so many factories and to lay off thousands of workers on the continent?

As can be seen from the chart, since about July 2012, the margin between the price of rough diamonds and 0.5 carat polished diamonds have been narrowing.

This has given rise to some increasingly bad-tempered exchanges between Philippe Mellier, the chief executive of the De Beers Group and the head of the International Diamond Manufacturers’ Association, Maxim Shkadov, who in January this year claimed that the margins of his members were close to zero. This tension between De Beers and many of its buyers will no doubt be aggravated by the reported jump in De Beers’s 2014 underlying earnings by 74% year on year – to $923-million.

The diamond-cutting industry has also fallen victim worldwide to the limiting of bank credit to the industry, which has made it even more difficult to operate.

As a result, gross margins are falling in the cutting industry, and diamond manufacturers are closing their highest-cost operations in Southern Africa.

There are no surprises in this, except for the fact that the deal the Botswana government made with De Beers in 2004, and revised in 2011, specifically required diamantaires who were Diamond Trading Company (Botswana) (DTCB) sightholders to cut and polish in Botswana.

Under this deal, the sightholders would eventually get $800-million worth of rough diamonds to process in Botswana. But they are not fools, and they knew at the time that Botswana is a high-cost location. So why did they set up operations here?

Industry sources have claimed that, in the past, the sightholders would occasionally get thrown a “special stone” by De Beers to compensate them for being in Botswana.

These stones are multimillion-dollar diamonds and the profit from one is often enough to compensate producers.

De Beers strongly denied this at the time but the practice has certainly come to an end. In 2012, the last year before diamond export figures became confused with re-exports associated with aggregation, Botswana exported diamonds worth about $4-billion.

If $800-million or so goes to DTCB sightholders, what happens to the other $3-billion that Botswana produces?

De Beers has 84 sightholders, according to its website, of which 21 are in manufacturing in Botswana. The rest take their diamonds out in one of the other four “boxes”, that is, Namibia, South Africa and Canada, where some of these De Beers sightholders have beneficiation obligations.

But a large chunk of all the diamonds produced in Southern Africa go into what used to be called the “London box”, which, since the selling operation was moved to Gaborone in 2013, is now called an “international sight”. Sightholders may get up to five boxes of diamonds at the Gaborone sights every 10 weeks. The international box can be sent anywhere for processing and so, in a bear market for polished diamonds, which it is at present, the local manufacturers, many of whom have access to an international box, can simply close their factories in Botswana, lose access to their Botswana box, but still continue production in India or China.

As Chaim Even Zohar, the guru of the diamond industry, said in a recent statement on the 2004 agreement: “There were penalties to be paid if the targets [of beneficiation] were not reached. In the current [2011] contract, I understand, the US$ value of local rough sales are still contractually agreed, but there is no agreed minimum employment level.”

This was done to allow the companies to use highly automated machinery but will have the effect of allowing these sightholders and De Beers to get off without the sorts of penalties in the earlier agreement.

What has happened to the diamond-cutting industry is what economists call regulatory failure. The closure of the factories in Botswana would probably never have occurred if the country’s agreement with De Beers had said that firms that do not beneficiate a portion of their sights in Southern Africa cannot have access to Southern African diamonds – full stop.

But, instead, we have created a complex marketing formula, which made the cost of leaving Botswana in the current bear market very low. The firms that closed their doors will continue to have access to Botswana’s diamonds. Thus, in a sense, the situation in which De Beers was claimed to have “subsidised rough with rough” has now been reversed – Botswana provides rough for the Indian industry at the cost of the country’s evaporating polished diamond industry.

If there had been an arrangement that said only those firms operating plants in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa could have access to De Beers’s African diamonds, the plant in Serowe would probably be open today.

Diarough will continue to operate its factories in India and Thailand, and neither it nor De Beers will suffer the consequences of the job losses.

Was this foreseen at the time the agreement with De Beers was signed in 2011? Almost certainly not – it was what economists call an unintended consequence of the negotiated marketing system.

Similarly, Botswana has imposed beneficiation obligations on De Beers but, at the same time, state-owned companies such as Okavango and private ones such as Lucara and Gem Diamonds are exempted from the same obligations. The buyers from these companies can take their stones to be cut in India. In this way, government policy encourages diamond trading but undermines Botswana’s beneficiation efforts.

It is time for Botswana, Namibia and South Africa to reconsider their agreements with De Beers and see what can be done to assure that diamond beneficiation in Southern Africa takes place in the way it was intended.

These are the views of Professor Roman Grynberg and not necessarily those of any institution with which he is affiliated.