When Kerry Hammerton was offered a chocolate chip muffin at a yoga function, her peers were astonished by her response. “I don’t eat sugar,” she told the waiter. “I’m a sugar addict.”

One of her yoga partners remarked: “Surely one would be alright? You’re not even fat.”

But Hammerton retorted: “If I was a cocaine addict, would you offer me cocaine and say it’s okay to just have a little bit? It’s exactly the same with sugar. If I have it, it will trigger my addiction.”

The yoga room flushed with surprise. “They thought I was crazy,” she recalls.

Hammerton had been struggling with fluctuating weight for years. In April 2013 she began following a low-carb-high-fat lifestyle that required her to stop eating sugar and also drastically reduce her intake of foods containing other carbohydrates. “Every time I eat sugar, it makes me crave more of it. It drives my hunger,” Hammerton says. “Sugar is addictive, like drugs are addictive.”

Cutting sugar is the “long-term solution”

Hammerton, who has lost 12kg since she began the new diet, is part of a growing movement of people trying to understand overeating, and the consequences of obesity, such as diabetes and related heart problems, in terms of food addiction.

One of the lobby’s biggest proponents is sports scientist Tim Noakes. Last week Noakes co-hosted an international summit in Cape Town, the Old Mutual Health Convention, on low-carb-high-fat diets.

On the website of Cape Town’s Harmony Addictions Clinic, which treats obesity as a food addiction by getting patients to follow Noakes’s low-carb-high-fat Banting diet, he proclaims: “The only long-term cure for obesity is to remove all addictive food choices [foods that contain sugar and other carbohydrates] from one’s diet. There is no other long-term solution.”

According to Hammerton, her food cravings disappeared when she stopped eating sugar and carbohydrates. “My metabolism stabilised as a result of this diet,” she argues.

But the science of sugar and carbohydrate addiction is not nearly as simple.

Mental order: Kerry Hammerton says she’s a recovering sugar addict.

Mental order: Kerry Hammerton says she’s a recovering sugar addict.

Scientists are divided

The field of sugar and carbohydrate addiction is divided between those who believe sugar and carbohydrates are as addictive as, or in some cases even more addictive than drugs or alcohol, and those who say true addictions are limited to psychoactive substances that produce symptoms such as physical intolerance and withdrawal.

All carbohydrates are ultimately sugar; sugar is a type of carbohydrate with simple chemical structures. During digestion, complex carbohydrates, such as those contained in food such as potatoes, rice and bread, are broken down into the simple chemical structure called glucose that the body uses as energy.

Some public health experts, such as Paul van der Velpen, who heads the Netherlands’s health department in Amsterdam, maintains that sugar is so harmful to our bodies that sugary products, particularly fizzy drinks, should be labelled with warnings such as those on cigarette packets. Such notices, he argues on the Dutch government’s website, should caution that sugar is a “dangerous addictive drug” associated with obesity and diabetes.

Last year, David Kessler, a former commissioner of the United States Food and Drug Administration, told the Mail & Guardian: “Fifty years ago the tobacco industry, confronted with the evidence that smoking causes cancer, decided to deny the science and deceive the American public. Now we know that highly palatable foods – [those with] sugar, fat, salt – reinforce and can activate the reward centre of the brain. We quickly became trapped in a vicious cycle of dopamine-fuelled urges when we want food and opioid releases when we eat.”

The “dopamine-fuelled urges” that Kessler refers to are connected to “feelings of reward”. Dopamine is a chemical, known as a neurotransmitter, in the brain that affects emotions, movements and sensations of pleasure and pain.

Studies have shown that dopamine is the key player in the reward system – which gives us that feeling of pleasure – of the brain. When we eat something that tastes good, our dopamine levels rise, making us feel good and, some scientists argue, wanting more of it.

Rise in obesity

A Lancet study last year found that overweight and obesity rates among adults have increased by 27.5% over the past three decades worldwide. The study reported that South Africa was the fattest nation in sub-Saharan Africa.

Researchers into sugar addiction have warned that the alarming rise of obesity has mirrored the use of high-fructose corn syrup as well a sharp increase in general sugar intake. High-fructose corn syrup is a liquid sweetener introduced in the late 1970s to enhance the taste of cereals, processed foods and soft drinks; it is found in most of those products in the US and consists of extremely high percentages of fructose, a type of simple sugar that is roughly 1.2 times as sweet as table sugar, according to the American Dietetic Association. In South Africa, however, sucrose derived from cane sugar is used more commonly as sweetener than high-fructose corn syrup.

A 2011 study, published in the journal Front Psychiatry, estimates that about 10-20% of people would present with addiction-like symptoms toward hyperpalatable [with high amounts of sugar] foods. According to a 2014 review of sugar addiction studies in the Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, this proportion is similar to the proportion of “cocaine or heroin users who go on to develop addiction”.

Not recognised as an addiction

But sugar and carbohydrate addiction is not recognised as an addiction in the “rule book” that most psychiatrists use to diagnose mental disorders: although the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) includes binge eating disorder as a psychiatric illness, it does not acknowledge it as an addiction. Binge eating disorder also does not apply to everyday overeating, but rather to a specific condition in which unusually large amounts of food are consumed in relatively short periods at least once a week over a period of three months.

The authors of the DSM, the American Psychiatric Association, only include conditions when they consider the available evidence for such illnesses to be conclusive.

Noakes argues that sugar and other carbohydrates make you hungry, so you overeat. “They do not satiate you and drive your appetite … Sugar, probably more than other carbs, drives that hunger and has fuelled, if not caused, the world’s obesity epidemic.”

But many of his peers have been highly critical of him for this.

No single nutrient to blame

In August 2014 Cape Town anaesthetist Luc Evenepoel, who published the diet book Dr Luc’s Promise – Lose the Weight and keep it Off (2012), warned in a letter published in the Star: “To blame one single group of molecules [carbohydrates] for two such mind-bogglingly complex problems [obesity and diabetes] is like saying that global warming is solely caused by the bowel gas of livestock.”

Stellenbosch University dietician Celeste Naudé agrees: “To demonise any single nutrient in isolation is not helpful. Yes, the load of added sugar in our food system is a big part of the problem, as are added fat and sodium [salt].

“But we should focus more on the quality of the foods and drinks we consume and less on blaming single nutrients – sugar-sweetened beverages are not the same as lentils, although both contain sugar and carbohydrates. The health effects of sugar added to foods and drinks during manufacturing are not the same as the sugar and carbohydrates occurring in fresh, whole foods such as milk and fruit.”

Several studies on rats have confirmed that sugar stimulates the same pleasure centres in the brain as psychoactive drugs or alcohol. One such study, published in the journal Neuroscience & Behavioural Reviews in 2008, found that, after a month of an intermittent sugar feeding schedule, the rodents showed “a series of behaviours similar to the effects of drug abuse”, such as bingeing, withdrawal and craving.

But critics have cautioned that the results of studies such as this one aren’t necessarily applicable to humans, as they analyse the behaviour of rats in controlled environments rather than that of humans in everyday living environments, in which a series of additional factors, such as personality, values, tastes and preferences, will influence people’s intake of sugar.

Sugar is a “hazard”

Some researchers, such as the authors of a study published in a 2013 study in Biological Psychiatry, argue that the ready availability and affordability of foods with high amounts of added sugar have turned sugar into a “serious modern hazard to public health”.

In a meta-analysis study, which reviewed 68 studies on sugar intake and its relationship to weight, researchers found that the more sugary foods participants consumed, the fatter they got, and the less, the thinner they became.

The study, which was published in the British Medical Journal in 2014, concluded that, “when considering the rapid weight gain that occurs after an increased intake of sugars, it seems reasonable to conclude that advice relating to sugar intake is a relevant component of a strategy to reduce the high risk of obesity in countries”.

But this study also stated that “isoenergetic replacement of sugars with other carbohydrates [that is, equal kilocalories in the diet from other carbohydrates] did not result in any change in body weight”.

A balanced diet may be the solution

According to Naudé, this finding demonstrates that total kilocalories fundamentally drives weight gain.

“The long-term solution to weight loss is not necessarily to cut carbs entirely from your diet, but rather to pay attention to your total kilocalorie intake and the foods you choose to eat,” says Naudé. “Different diets work for different people. The most important thing is to find what helps you keep your energy intake in check and to make quality food choices for good nutrition. Steering clear of aggressively marketed, ultraprocessed, highly palatable, energy-dense foods, loaded with added fat, sugar and sodium (such as junk food: fast foods, chips, pastries, chocolates and fizzy drinks), is half the battle won.”

Research that Naudé and her colleagues at the Centre for Evidence-based Health Care at Stellenbosch University conducted last year, in which the results of 19 clinical trials were pooled, found that low-carb-high-fat diets did not result in more weight loss than traditional balanced diets in the long term when kilocalories in the diets were equal.

A 2012 study in the Nutrition Journal, which followed the self-reported food and nutrient intake and measured body weight of 14 000 Swedish men and women over a period of 25 years, had similar results: it found that a low-carb-high-fat diet, which contains significantly less sugar than balanced diets, was not associated with less body fat.

Sugar tax

In South Africa, a growing number of health experts and consumer bodies have been calling for a sugar tax of 20% on products that contain high amounts of added sugar, such as soft drinks, as a way to curb South Africa’s increasing obesity levels. As a result, a sugar tax is being considered by the health department.

The University of the Witwatersrand has reported that a 20% tax on sugar-sweetened beverages could lead to more than 220 000 fewer cases of adult obesity in the country. South Africans drink large amounts of sugar-sweetened beverages: In 2010, intake was almost three times greater than the global average, according to Naudé. Reducing the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages is seen as one strategy that could help reduce kilocalorie intake and obesity.

Does that mean sugar is addictive, and if so, to the same extent as drugs and alcohol?

Is sugar addiction real?

Not necessarily, say the authors of the Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care review: while there is evidence in non-humans – mainly rats – that foods high in sugar can induce reward and craving responses that are at least comparable to those of addictive drugs, this has not been proven conclusively in humans.

“In most cases … the experienced psychoactive effects of sweet foods is mild and does not seem to match those of drugs,” the authors conclude. “In other words: sweet foods are clearly not as behaviourally and psychologically toxic as drugs of abuse can be at high doses.

“For instance, unlike drugs, consumption of hyperpalatable foods, even [when] extremely high in sugar, does not produce any abnormal mental state or change in behavioural disposition.

“This explains why no police officer will arrest a driver because he or she had eaten several doughnuts before driving the car or why no judge will consider drinking half a gallon of sugar-sweetened soda before committing a crime as a mitigating circumstance.”

Stuck on the sweet, sweet road to obesity and self-loathing

On a Wednesday night in April 2013, Tania Bosman (23) arrived at her brother’s house in Brackenfell, near Cape Town, with all his favourite snacks – Simba and Doritos chips, Zoo biscuits and Salticrax.

“I wanted to spoil him because he had broken his foot … the day before,” she recalls. Bosman arranged the nibbles on a few plates on the kitchen counter and positioned herself next to them. She started to eat. And eat. And eat … she just couldn’t stop.

Soon, Bosman, who weighed 145kg at the time, realised she was eating far more than her brother and his friends. She felt embarrassed and stopped.

It wasn’t the first time. At work Bosman would hide snacks in her drawer. “I would only eat in front of people if it was healthy foods because I didn’t want them to know I was eating chocolates. Obviously you could see that I had an eating problem – I was enormous – but I tried to hide it as much as possible.”

But on that April evening at her brother’s house, one of his friends, who had just been released from a drug rehabilitation centre, started to talk about his drug addiction. “As I was listening, I thought, maybe I have a similar problem with eating. So many of the emotions he experienced with drugs, I experienced with food: cravings, binges and withdrawal symptoms,” she recalls.

When she got home, Bosman googled “food addiction”. She stumbled on to the Harmony Addictions Clinic in Hout Bay’s website.

There she found the “Harmony Eating and Lifestyle Programme (Help)”. “Do you find carbohydrates and sweet fatty foods difficult to manage in moderation, often leading to overeating and binge eating?” a question on the programme’s website asked. “Do you experience guilt or shame due to your eating behaviour?” And finally: “Do you feel better after eating sweet foods or feel withdrawal when trying to cut these out of your diet?” If so, according to the website, you might be addicted to carbohydrates and sugar.

Tania Bosman has lost 37kg on the low-carb-high-fat diet.

Tania Bosman has lost 37kg on the low-carb-high-fat diet.

The next afternoon, Bosman enrolled herself in an eight-week carbohydrate and sugar addiction treatment programme as an outpatient at the clinic. “While I discovered that, emotionally, I eat to suppress my feelings, I also learned that the carbs – and sugar is a carb as well – made me crazy. It made me moody and depressed but, most importantly, constantly hungry.

“It became very easy to accept I was a sugar and carb addict, because it made sense.”

Help dieticians put Bosman on sport scientist Tim Noakes’s low-carb-high-fat diet, known as Banting. It contains unusually low amounts of carbohydrates and sugar. She lost 37kg over the past 22 months – the longest that she’s maintained weight loss on a diet.

“It curbed my hunger,” Bosman says. “I used to eat three to four slices of bread [which is high in carbohydrates] when I woke up for breakfast. “By 10am I was starving and I wanted something else. It was always bread, crisps, chocolates or pies – that kind of stuff – that I would then start to binge on. “But now I have a high-fat breakfast of egg and bacon, and I can go for five, six, sometimes even seven hours without eating again, because I’m legitimately not hungry. This is what works for me.”

Just two spoonfuls of sugar …

Sugar should make up less than 10% of our daily energy intake, according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) draft guidelines. That works out to about 50g or 12 teaspoons of sugar for a person of normal weight.

The WHO further recommends that a reduction to below 5% (six teaspoons) would have additional benefits for dental health.

A 2012 study published in the British Medical Journal reported that South Africans consume an average of 84g, of sugar a day – far more than what is good for us.

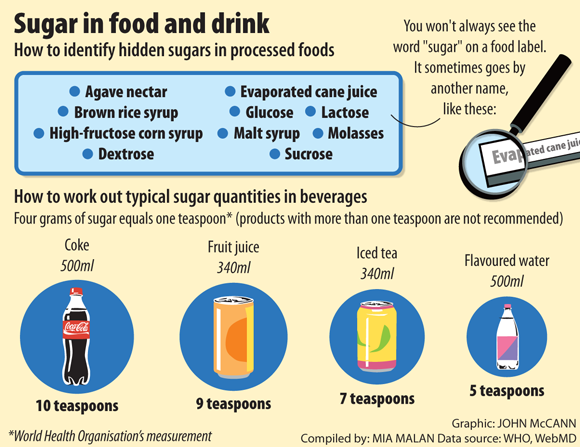

Much of the sugars consumed today are “hidden” in processed foods that are not usually seen as sweets. According to the WHO, one tablespoon of tomato sauce contains about four grams, or one teaspoon, of sugar.

A 500ml bottle of sugar-sweetened soda, such as a Coke, has 40g, or 10 teaspoons, of sugar – almost the entire recommended daily sugar allowance. Up to half of grade eight to 10 pupils in South Africa in 2008 were reported to be consuming fast foods, cakes and biscuits, cool drinks and sweets at least four days a week, according to Stellenbosch University dietician Celeste Naudé.

This is the second part in a two-part series on sugar and carbohydrate addiction and low-carb-high-fat diets