Archbishop Desmond Tutu and other members of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission at the first TRC hearing in East London in 1996. But the process of healing has not yet ended.

Ruth is afraid, and with more reason than most.

In a prison somewhere are the men who killed her husband, her son and several members of her extended family during the brutal years of South Africa’s transition. Or so she would like to believe. She is not entirely clear about the identity of the killers, and knows nothing about what punishment may have been meted out to them. She does know that people were arrested, and that the killings stopped at roughly the same time. To date neither the people nor the violence have returned.

“If they come back, what must we do? Last time we locked the doors … they broke them. If they want to kill, how do you stop them?”

Ruth’s one comfort is that, unlike in the mid-1990s, her village in the Midlands of KwaZulu-Natal now has cellphone service. Perhaps this time, if the men with the guns and the pangas come, she’ll be able to phone the police. Perhaps this time it will be different.

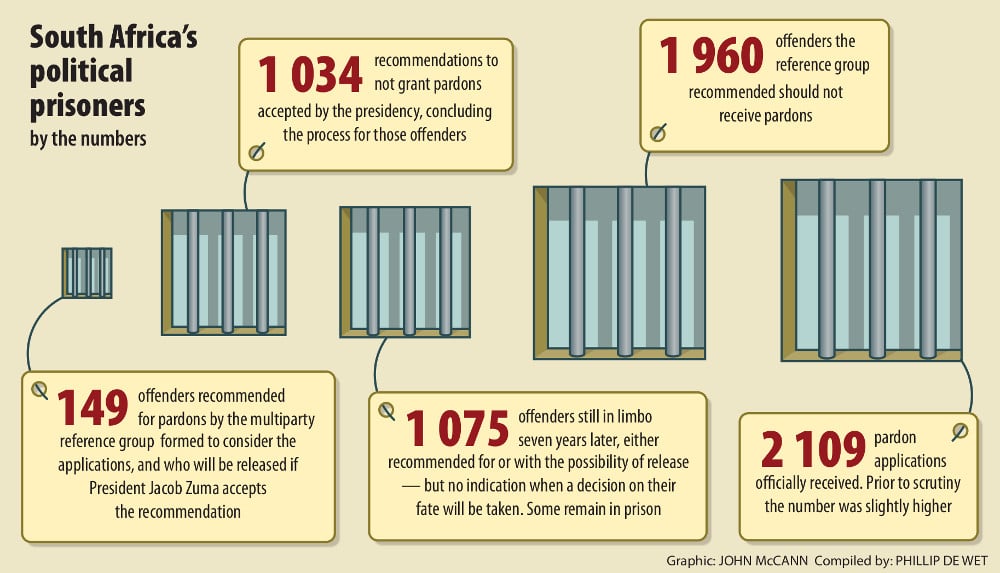

The men Ruth fear may, or may not, be among 926 people who once again stand some chance of a presidential pardon for crimes committed in the name of politics up to the middle of 1999. If they are pardoned those men may, or may not, be released from prison without fully disclosing their crimes. They then may, or may not, return to the communities they once terrorised, with possibly violent consequences. Even if they are not the perpetrators.

“I’d say it’s more the ones coming out who would be in danger,” says Steve Collins, who was a community conflict mediator for the Institute for a Democratic Alternative for South Africa at the time. “If you don’t have a peacemaking process you can have family members [of victims] saying ‘there is no justice here’ and taking things into their own hands.”

These are the extreme ends of a spectrum of concerns that also include released offenders turning to robbery and hijacking, or finding themselves homeless and without any means to build their lives anew.

Such is the nature of the renewed process seeking, again, to wrap up the “unfinished business” of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). It could see the freeing of the last of South Africa’s political prisoners, or those defined as such by the fact that political parties took some responsibility for their actions. It could, finally, draw a line under the bloody transition to democracy between 1994 and 1999. If poorly managed – as it has been so far – it could also lead to more fear, and more violence.

But most likely, it will lead, again, to civil society organisations bitterly opposing politicised absolution for those behind racist killings, farm murders, taxi violence and assorted heinous crimes, while the families of victims and perpetrators alike are left in suspense.

Pardons delayed

In a cruel twist, even the announcement that pardons for political crimes were back on the table – albeit without timeline or deadline – was itself delayed.

“All applicants will be informed as soon as I have taken a decision on this matter,” President Jacob Zuma told Parliament in a written reply to a question on February 10 this year. That reply was due to have been delivered verbally on August 21 2014, the presidency said, but that parliamentary session was interrupted by the Economic Freedom Fighters’ demands that Zuma should “pay back the money”.

The commitment was worded almost identically to those made in 2013, 2012, 2011 and, in fact, on average once a year, every year, since the end of 2007.

It was in November 2007 that then-president Thabo Mbeki first announced a decision intended to close the book on a long-running political problem. Using his constitutional power to pardon convicted criminals, Mbeki said he would consider applications for such a pardon by anyone guilty of a politically motivated crime up to the end of Nelson Mandela’s presidency.

The straightforward nature of the announcement belied the complex machinations behind it. For much of his first term Mbeki had come under intense pressure from the likes of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC)to release some of their members imprisoned after the orgy of violence during the post-1994 transition. For a president in his second term and with an eye on his legacy, there were many reasons to run a lightweight version of the TRC with a focus on events in the fraught five years after the first democratic elections in 1994.

But although the IFP in particular led the charge, there were also calls for clemency from the opposite end of the political spectrum, from former apartheid apparatchiks and members of white far-right organisations. This being some three years before the death of Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) leader Eugène Terre’Blanche, there were practical security as well as philosophical reconciliation reasons to consider a wide range of perpetrators for pardons.

The solution to the resulting political problem was a political one. From the outset Mbeki made it clear that the final decision on any pardon would be his, and his alone, as is the nature of presidential pardons. But he would consider the recommendations of an ad hoc committee, a “reference group” with representatives from all political parties then in Parliament.

It turns out that politics can complicate matters.

“This is perhaps the clearest indication of the ‘horse-trading’ that took place in the [reference group],” a group of civil society organisations under the name of the South African Coalition for Transitional Justice would later write in an analysis of the work of the reference group, and that body’s apparent willingness to “accept any claimed political objective – even when no proper political objective could factually and objectively exist”.

The pardon process required political parties to take responsibility for the crime committed with a sworn statement to say the act had been, if not necessarily on the instruction of the party, then at least in “promotion or achievement of” its interests.

But the criminal need not have been a member or agent of the party; identification as a “supporter” would be sufficient.

This, the transitional justice group believed, made for a quid pro quo environment in which nobody stood in opposition to the possible release of contract killers, racist attackers and even everyday robbers who claimed they were in the business of redistributing wealth.

But that is supposition drawn from the work of the reference group – still secret years later – because the body kept no minutes that have ever been disclosed, and those involved (several have since retired from politics) have yet to speak about its work.

The political veil of secrecy extended to cover both victims and perpetrators. The reference group would not publish a full list of those who had applied for pardons, and to this day the identities of all but 149 of the offenders affected remain unknown.

These 149, or just over 7% of those who formally claimed they were missed in the TRC process and deserve to be treated as political criminals, know at least who they are, but not when they will be told whether they will receive pardons. Nor is it clear whether they have fully disclosed their actions in the name of politics, or whether there are many more people like Ruth who do not know the identities of their attackers.

“Our people spent about two weeks walking up down the hills of the Midlands,” says Marjorie Jobson, who heads the Khulumani Support Group for victims of apartheid, of a rushed 2010 process around victim input for a final decision on the 149 named offenders. “The overwhelming response was ‘the people who came into our huts and killed so many members of our family wore balaclavas. We don’t know who they were. We were never called in court.’?”

It gets even more complicated further down the list. As of this February, another 926 people still stand some chance of a presidential pardon, despite not being recommended for pardons by the reference group. Neither the public nor their victims know who these people are because the list of names has never been released. In at least some instances, it seems, not even the individual offenders know whether they form part of this group.

Of this 926, some are still serving life sentences. Or so believe the likes of the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (Apla) and the IFP, which have members and supporters behind bars who they believe should be on the undisclosed list.

Even if a disclosure and reconciliation process were forced upon the offenders – a step many believe is not only morally required, but the only way to prevent future violence – it is far from certain that these 926 offenders can be put in touch with surviving victims or their families.

The Midlands, which saw a succession of political massacres and revenge attacks, was a success story, relatively speaking, as was tracking down the families of victims of an AWB bomb attack in Worcester on Christmas Eve 1996. Other perpetrators have been in touch with their victims, such as apartheid-era law and order minister Adriaan Vlok, who dramatically washed the feet of clergyman Frank Chikane, who Vlok attempted to murder.

In many other cases the details seem lost to history, with even court judgments (some of them limited in detail thanks to plea bargains) no longer available. Who did what to whom and why is murky, sometimes impenetrably so. One consequence – and from the point of view of civil society groups perhaps the most important consequence – is that to date it has been impossible for those to whom violence had been done to be heard. And on that basis these organisations again stand ready to go to court to prevent the pardons from being issued, as they have successfully done in the past.

“Counsel for the applicant argued that the requirement of victim participation was met through the process set in place by the president which involved all the political parties represented in Parliament,” Justice Johan Froneman wrote in an addendum to a unanimous Constitutional Court judgment on the pardon process in 2010. “Put differently, the argument was that representative democracy was sufficient in the circumstances. It is not.”

The Constitutional Court was brought into the fray towards the end of 2009 by Ryan Albutt, an AWB supporter convicted for a racial attack in Kuruman in 1995. The state found itself arguing alongside Albutt that victim participation was not required for the pardon process, and that a high court order interdicting the granting of the pardons should be set aside.

The Concourt was not biting and, instead, declared in no uncertain terms that the “special dispensation” was, in effect, a mini TRC, and thus was bound by similar requirements.

“It is apparent … that the special dispensation process had the same objectives as the TRC, namely, nation-building and national reconciliation. While the TRC process sought to achieve this through amnesty, the special dispensation seeks to achieve these objectives through pardons,” then chief justice Judge Sandile Ngcobo wrote in dismissing Albutt’s appeal.

“Excluding victims from participation keeps victims and their dependants ignorant about what precisely happened to their loved ones; it leaves their yearning for the truth unassuaged; and perpetuates their legitimate sense of resentment and grief. These results are not conducive to nation-building and national reconciliation. The principles and the spirit that inspired and underpinned the TRC amnesty process must inform the special dispensation process whose twin objectives are nation-building and national reconciliation.”

Thanks to that decision the short list of 149 names recommended by the parliamentary committee for pardons was later published, and other details provided to the Transitional Justice Coalition. The trickle of documents provided revealed that the reference group considered people guilty of taxi violence and stock theft, farm attacks and possession of automatic firearms.

“There were cases anyone might be sympathetic to, but there were also cases like someone who claimed to have committed a robbery in the late 1990s to raise money for the PAC,” says Hugo van der Merwe of the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, which played a key role in the Transitional Justice Coalition alongside Khulumani.

After the last long delay in the process, and with a firm Concourt decision in hand, that coalition had assumed the special dispensation process had gone away. Then Zuma told Parliament it was resurrected, and the opposition to the process was also revived. They have already sought (though failed to secure) a meeting with Justice Minister Michael Masutha, the member groups of the transitional justice group told the Mail & Guardian. First they intend to raise their concerns, again, about the sidelining of victims and ordinary criminals opportunistically but implausibly claiming political motives. Should that fail, they are ready to go to court.

Between the delays and the uncertainty, nobody is able to prepare properly for the conclusion of the pardon process, and few have a sense that justice is being served, not even those who represent perpetrators who could be released.

“If people just come out, we won’t be prepared if they have nowhere to go,” says Xola Tyamzashe of the Apla Military Veterans’ Association. “You can’t pardon and then have people on the street. That is not justice.”

A timeline of delays

October 29 1998: The TRC hands its final report to Nelson Mandela.

June 16 1999: The cut-off date for political crimes to be considered for pardon. Thabo Mbeki is inaugurated as president.

November 21 2007: Mbeki announces a “special dispensation process” to consider pardons for political prisoners. He is expected to conclude the process before the end of this term; the term is cut short.

January 18 2008: The Pardon Reference Group is constituted.

February 2008: Nongovernment organisations start a campaign to insist victims be heard in the pardon process.

May 31 2008: The submission deadline for pardon applications under the special dispensation.

August 2008: The reference group tells NGOs there is no need for victims to be heard.

September 20 2008: Mbeki announces his resignation.

March 2009: The presidency refuses to hear victims as part of the pardon process.

April 29 2009: Pretoria high court grants an interdict preventing then-president Kgalema Motlanthe from granting pardons under the special dispensation process until the matter of victim participation is settled.

November 2009: Motlanthe tells the Constitutional Court he intends to deal with the applications.

February 23 2010: The ConCourt dismisses an appeal against a high court ruling holding that victims must be consulted.

March 24 2010: President Jacob Zuma tells Parliament he will consider the reference group’s recommendations.

October 2010: The justice department publishes the list of 149 offenders considered for pardons. This launches a three-month process for interested parties to make written submissions supporting or opposing pardons.

November 2010: NGOs request documents relating to the proposed pardons.

January 2012: NGOs receive copies of the applications by and reports on some of the prisoners recommended for pardons.

February 2012: Some prisoners who applied for pardons receive letters saying representations from victims were being sought.

November 12 2013: Zuma tells Parliament the pardon process was delayed by the need to call for public comments. “All applicants will be informed as soon as I take a decision in this matter.”

January 30 2015: Justice minister Michael Masutha announces the revival of the 2007 special dispensation process.

February 10 2015: Responding to the IFP, Zuma tells Parliament applicants will be told about the applications’ outcome once he has decided.

March 2015: NGOs hope to meet the justice department to explain their opposition to resuscitating 2007’s process.