Hlengiwe Vilakati

Gender bias in the South African art sector favours women, but the “hypervisibility” of a handful of black artists and curators obscures the fact that true transformation is more elusive.

Speaking out against institutionalised whiteness in the South African art system came at a huge cost to Sharlene Khan. She received hate mail, her employer received defamatory letters urging her to fire Khan, gallerist Monna Mokoena was told not to exhibit her work, she was humiliated in scholarship interviews, newspapers did not print her exhibition listings and, with two master’s degrees to her name, she was unable to find a lecturing position for four years. Her crime? The “Doing it for daddy” article in Art South Africa magazine in 2006.

“White domination of the visual arts industry is overwhelming; the dominance of white females especially glaring,” she wrote, going on to decry the fact that, 12 years into our democracy, the patriarchal apartheid system had been replaced with a warped system that prioritised redressing gender inequality. Win for feminism perhaps, but in a country with more than 90% of its population being people of colour, this was less than even half a win for transformation.

“It is easier to talk about transformation than to actually invite people in to talk for themselves,” says Khan over Skype from London, where she has just completed her PhD at Goldsmiths, University of London. She admits that she’s ambivalent about talking to me and dredging it all up again, with the possibility that I would misquote her. After all, she did publish an extensively researched sequel article five years later in 2011, in Artthrob.

Yet, it’s nine years since the original article shut down her local career, forcing her to find employment as a personal assistant for four years, and it seems more relevant than ever – as it became clear to me in researching this article.

A Vanity Fair article about female art dealers in the United States was what inspired the Mail?&?Guardian’s arts editor, Zodwa Kumalo-Valentine, to ask me to look into writing something similar here. It seems Facebook’s spybots had been eavesdropping and on the same day an Artnet article polling 20 women in the art world about bias appeared on my newsfeed. A Financial Times article about sexism in the investment banking industry gave the idea for a survey.

In working on a list of women to speak to, it became immediately clear that we had to expand the ambit from dealers and gallerists to curators as well because, not only were they all blandly pale and somewhat wrinkly, it’s not clear anymore whether the dealer or the curator chooses what artists to show, and curators are sales women too.

In retrospect, this process was somewhat flawed. The survey did not offer any meaningful statistics – besides an overwhelming 79% of respondents who thought the sector was race- and gender-biased, although these questions should probably have been asked separately. Moreover, we’re in South Africa and importing these Westernised story structures cannot encapsulate the unique history and dynamic of our fine-art sector.

As interviews began, particularly with Portia Malatje, who, after just over a year as head curator at Brundyn+, left at the end of February, it also became clear that the real story was just outside “the system” – like Khan and independent curators such as Gabi Ngcobo, who has recently been announced as one of the four curators of the São Paulo Biennial.

Gabi Ngcobo (Photo by Masimba Sasa)

‘They all dressed the same – black leather jacket and stovepipe blue jeans – and smoked Gauloise with no filter,” Emma Bedford recalls her all-male lecturers in the 1970s. Fine-art specialist at Strauss & Co auctioneers, Bedford is renowned for being the founding director of the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, following 25 years at the Iziko South African Museum. “They would stand in a circle and women wouldn’t count at all – you were only there to get married. Enough to turn you into a hardcore feminist.”

Yet, as both Bedford and Carol Brown recall, studying art was the done thing for women, in that era of “BA-mansoek”. Whereas men got on with the real business, art did not have much stature. Brown, the Durban-based curator who founded Red Eye while director of the eThekwini Art Gallery, started out as a secretary studying through Unisa. Many others rose through the academic ranks and remain heads of departments and institutions to this day – another aspect overlooked in our initial scoping of the article.

Linda Givon, the doyenne of contemporary art in South Africa and founder of the Goodman Gallery in 1966, in particular recalls being ridiculed by drunk businessmen who would come into the gallery after lunch “to torture the women”, making them haul every artwork out of storage and demanding ridiculous discounts.

“I was earning less than my male counterparts in the same job and I was not eligible for a housing subsidy,” continues Bedford. “But our director, who was a man, set about challenging those things. You don’t have to be a woman to be a feminist. I’ve seen these things change over time.”

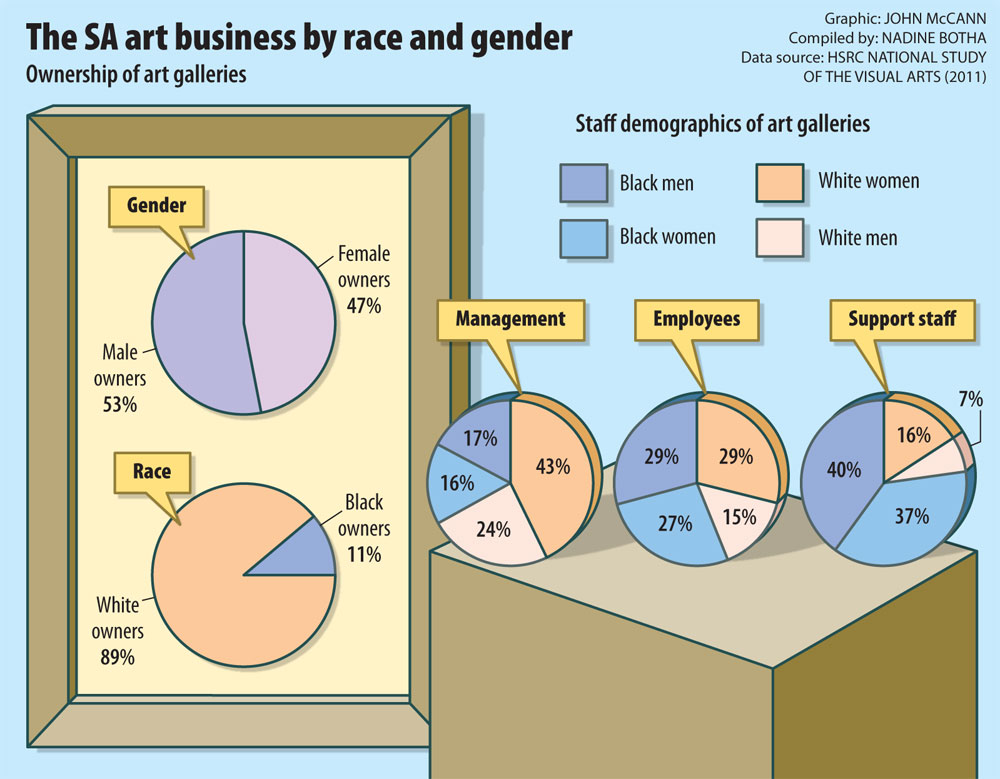

According to statistics released by the Visual Arts Network of South Africa in 2011, the breakdown of women and male business owners is 47% to 53%, relatively gender equal until you look at employees. In senior and middle management a dramatic 43% are white women and 16% black women – the smallest segment – making a total of 59% women.

In terms of racial transformation, the 60% employees of colour sounds positive. But the overwhelming majority – 77% – of these are in technical, ancillary and volunteer positions. On management level, there are only 34% of people of colour. In terms of overall employment, white men are the most marginalised at 15%.

Thus it would seem that South African women have succeeded at gaining parity within the patriarchal art system, despite the universal biological odds of having children and continued imbalances around home chores. These conventional gender challenges are all that most of the curators have experienced.

“It’s very tough to be a career woman and have children,” says Liza Essers, who bought the Goodman Gallery from Givon in 2003. “Especially in the art world where there is a huge requirement to travel internationally in terms of the number of art fairs we do a year, 50% of our clients are based out of the country, a number of our artists are overseas, and our artists also have major exhibitions all over the world.”

Elena Brundyn, owner of Brundyn+, says she has not once been home while her children were writing exams, and has never felt comfortable travelling alone. Bedford recalls her hair falling out while she was working at Iziko, studying for her honours degree and breastfeeding her child, all at the same time.

Lucy MacGarry

Lucy MacGarry, newly appointed curator of the FNB Jo’burg Art Fair, describes an amusing incident in which she was manning a stand for her L’MAD fashion business at Handmade Contemporary, looking after her one-year-old and being interviewed by a journalist. Who said multitasking is a myth?

Yet, as Bedford so succinctly points out: “White women have it easier; we can work because there are women who work for us.” And herein lies the problem with just looking at feminism from a gender perspective. Instead, a much more intersectional feminist approach that considers other privileges such as race and class is needed, especially in South Africa.

“There are historical challenges to being a black female, which filter into the art space. You have to fight harder to be seen, just to be seen. The question of visibility is also complex,” says Ngcobo, calling the media’s tendency to make black female curators hypervisible a catch-22.

Malatje refused to be interviewed if this was going to be one of those articles, explaining that the disproportionate media attention “starts to feel like the scene is very balanced”.

Nontobeko Ntombela, formerly a curator at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), describes hypervisibility as a form of ridicule: “Here’s a few black women curators so let’s put them out there and promote them as hard as we possibly can, without giving people the opportunity to really produce quality work, again as another gatekeeping strategy because how long do those people last? They’re there for a moment, they serve a purpose and then they are rejected.”

After two years as curator of contemporary collections at JAG, Ntombela was “angry” with the establishment and systematic gatekeeping when she left in 2012. She went on to found the curatorial studies course at Wits University and sits on the advisory committee for the department of arts and culture, among a very long list of other accolades.

“The idea of the establishment becomes even more complex: Who are you talking about in terms of the establishment? It’s neither white nor black. It’s a mix of everybody, but what the establishment understands and frames as giving value to art is the larger question,” Ntombela says. “I’d rather produce shows that I’ve invested research, time and space into, which academia allows for. It was frustrating being part of that hypervisibility and need to curate as many shows as possible, rather than develop a signature.”

Almost everyone agrees: racial transformation has been too slow.

In terms of ownership, 89% is still white-owned, although nearly every interviewee said the only black gallery owner is Mokoena of Gallery Momo in Parktown North, Johannesburg. In terms of staff, said gallery owners Brundyn and Essers, people of colour are difficult to find.

For Ntombela,“it starts in the classroom: what is being taught, how is it being taught, becomes another embedded, very important key thing that also needs to be included in the transformation question”. She goes on to explain that black women studying art but going into arts administration has become a natural progression because of the way certain students are highlighted, giving a sense of defeatism to the rest.

Ernestine White

The gap between the classroom and the hypervisibility is the crux for Ernestine White, curator of contemporary art at Iziko for almost a year. “If artists don’t make it into a Goodman Gallery or a Stevenson Gallery, they struggle and are forced to find other ways of making ends meet. Some stick with it, some don’t. The industry needs to learn how to be more friendly to those artists,” she says, calling for more bursaries and residencies that allow artists to grow without commercial pressure.

Providing incubation space for artists aged 25 to 35 is what Hlengiwe Vilakati, an advertising industry refugee-turned-gallery owner, hopes to achieve with Jo Anke Gallery.

Established in 2013, the Orange Grove gallery is one of several independents that have popped up in Johannesburg over the past few years, ranging from project spaces such as the Centre for Historical Re-enactments used by Ngcobo to the flash-mob-attracting likes of the Kalashnikovv gallery in Braamfontein run by MJ Turpin.

“In the last two years I’ve seen a resurgence of people saying, ‘fuck it, let’s do it on our own and see where it takes us’,” says Maria Fidel Regueros, a Zimbabwean who started working in South Africa in 2001 with the Joubert Park art project. She now owns Room in Braamfontein, which tries to be a project and gallery space at the same time.

Possibly, it is exactly these “lighter, quicker, cheaper” start-up galleries that will realise transformation, by redefining the structure, balancing content with commerce, and drawing new audiences. Even Givon says that artists no longer trust commercial galleries. She wouldn’t.

Complete independence from galleries, publications and universities is the route Kahn has cemented for herself over the past few years, in preparation for returning to the country in March. As a final thought on Skype, she concludes: “It’s not okay in a country with 90% of people of colour to still have art departments that are entirely white with one black workshop co-ordinator. But no matter who you are, black or white, we all need to work on decolonising the system.”