The state wants a rapid roll-out but is sitting on substantial unused spectrum.

COMMENT

Universal access and service is designed to ensure that every South African, no matter how remote their dwelling may be, is able to connect to the national information and communications technology (ICT) framework and to the developmental and social resources available through it.

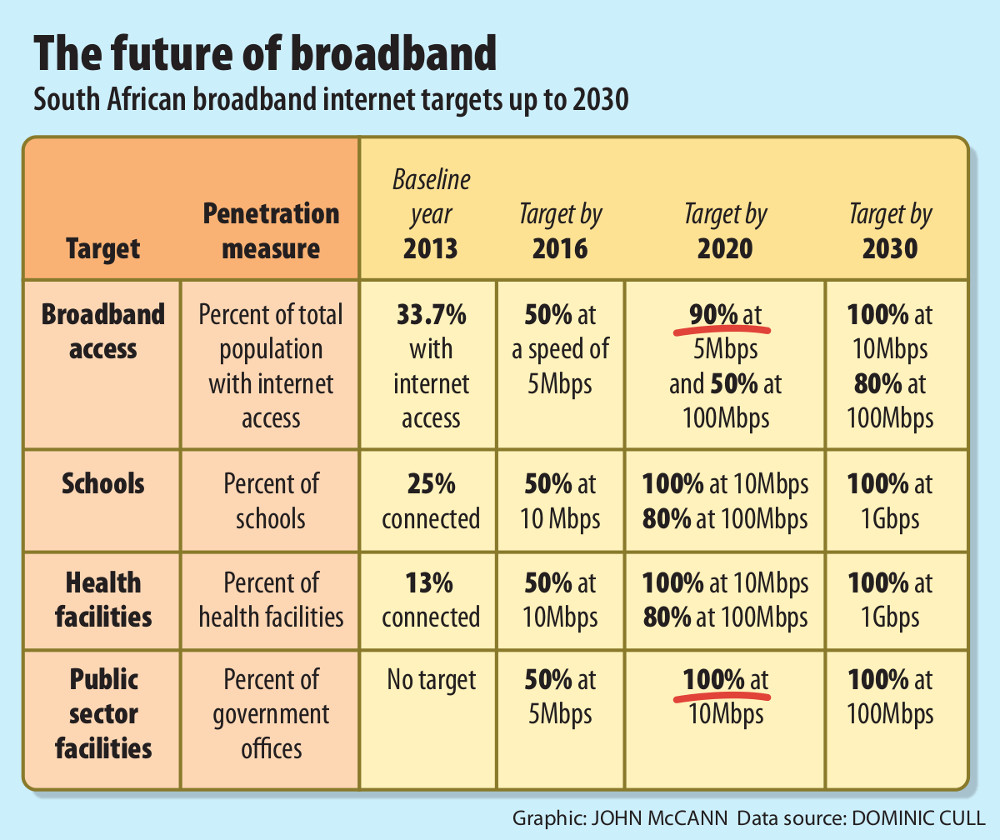

Universal service and access targets are set out in the South Africa Connect Broadband Policy, published in December 2013.

Access to communications has a profound effect on individual lives. The South African Connect Policy also acknowledges that increases in broadband penetration correlate with increases in gross domestic product, new jobs, educational opportunities, enhanced public service delivery and rural development.

The 1995 white paper on telecommunications, the 1996 Telecommunications Act and the 2005 Electronic Communications Act all sought to promote universal service and access. The Universal Service and Access Agency of South Africa (Usaasa) was established to push things along and the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (Icasa) imposed and administered universal service and access obligations to be observed by some licensees. All licensees were required to contribute a percentage of their revenue from licensed services to the Universal Service and Access Fund, administered by the agency and to be used to reach universal access and service goals.

Government policy recognised that the commercial players could not be relied on to provide universal access and service because their primary motivation is profit, and remote areas are not generally regarded as being commercially viable (or, at least, as commercially attractive). Telkom, for example, regularly bemoans the cost of cross-subsidising loss-making rural services, which it provides.

Progress has been made. The outstanding transition in providing communications for all has seen the shift from universal access and service targets focused on voice services to targets focused on broadband services. Government policy and a specialised institutional framework notwithstanding, this success is attributable almost solely to the unexpected level of uptake of cellphone communications by users of all living standards measure groups and the rapid developments in the technology used to provide us with voice (and now data) services.

At the same time, the government’s managed liberalisation policy suppressed competition in favour of Telkom extending its copper network to the broader population. This was not a success, either for the nation or for Telkom.

Area licences

Policy also sought to combine industry transformation, universal service and access objectives through the ill-fated underserviced area licensee intervention. Licences to deploy networks and provide services in underserviced municipalities were awarded to local entities and empowerment groupings, which were left high and dry without the promised support from Icasa, Usaasa and the department of communications. This was not a success for universal access, transformation or the licensees, most of which imploded, resulting in liquidation, sequestration and recrimination.

Icasa’s enforcement of the universal service and access obligations has been abysmal. A scathing report, Universal Service and Access Obligations Compliance Review of Licensees for Icasa, compiled by BMI-TechKnowledge and Mkhabela Huntley Adekeye in March 2010, states that Icasa has failed to monitor and report on the compliance of existing licence holders, with the result that there has been “very minimal compliance” with the obligations.

A process to review these was concluded earlier this year. But, for the most part, it restates obligations that Icasa is still not in a position to monitor and enforce.

Usaasa, though showing signs of recovery, has lurched from one crisis to another, and a special unit investigation is continuing. It is unclear how the funds contributed by licensees were disbursed.

The list of implementation gaps is overwhelming: schools connectivity has been failed by many unco-ordinated initiatives and false starts, as well as the failed e-rate policy initiative, which Icasa appears to have given up on implementing in a sustainable manner. Using post offices as community communications hubs has been articulated in various forms for decades, but little progress has been made.

Reductions in wholesale call termination rates aside, little has been done by the government and its agencies to reduce the cost to communicate, especially for rural South Africans.

Long-term initiative

The initiative to deploy broadband networks in eight underserved areas, announced by the president in his State of the Nation address, is to be welcomed, notwithstanding a lack of clarity over funding. But this will be long term, with uncertain outcomes and limited effect.

Implementation’s biggest failure has been and remains the government’s and Icasa’s failure to issue licences for radio frequency spectrum to the ICT industry. Leaving aside the digital dividend spectrum held hostage by the again-delayed digital migration process, there is substantial spectrum that could and should have been released to the industry to enable existing providers to improve their range and quality of service and enable competition and transformation.

The opportunity cost of the failure to employ spectrum assets productively to the economy – measurable in foregone growth increases – and to the quality of lives, is staggering and inexplicable.

If we consider the 2020 universal access and service targets set out above – 90% of the population having access to a 5Mbps (megabits per second) broadband service – it should be obvious we must rely heavily on cellphone networks and other wireless providers to achieve this.

Driven by commercial interests and consumerism, fixed fibre networks are being deployed at a rapid rate in metropolitan areas – in spite of the government and Icasa rather than thanks to them – but, if we are to achieve our short- to medium-term targets, this will have to be done through a combination of wireless access services complemented by fixed fibre backhaul services.

Radio frequency spectrum

This is not impossible, but it will be if the necessary radio frequency spectrum is not made available to the industry as soon as possible.

But the signs are that this urgency is not appreciated. The president’s decision to split the department of communications into two last year continues to confuse, confound and frustrate industry stakeholders, and new policy on spectrum – both unnecessary and already long delayed – is now expected only in March next year.

If we want to do more than pay lip service to economic growth, job creation and poverty alleviation through universal service and access, the government must recognise the potential of broadband to meet developmental challenges. It will need to overcome its distrust of an independent communications regulator and recognise that a strong Icasa is a prerequisite for any progress, and to ensure that the policymaker must facilitate rather than hinder progress.

The market has not failed. It is the government that has failed to grasp and act on the opportunity presented by communications and broadband to meet its goals.

Dominic Cull specialises in telecommunications law.