Art of survival: Despite funding problems

It’s been 12 years since the death of artist Nhlanhla Xaba inside the printmaking studio he cofounded in Newtown, Johannesburg. Not many detailed reports can be found online about how he died in a fire on March?9 2003. But an A5 pamphlet for a current posthumous exhibition paints a picture of him falling asleep on a couch in the Artist Proof Studio before “a suspected electric short from a kettle” caused the blaze, which ripped through the studio and killed him.

READ:

Art institutions and their ticket to survival

Black artists must hitch their wagon to BEE

More than a decade later, at the Nhlanhla’s Open Chair exhibition, the walls of the reconstructed Artist Proof Studio are lined with evocative, scratchy prints that capture the angst of a country in turmoil.

From the time he started working on his art in the early 1980s until his untimely death, what Xaba was exposed to – from the state of emergency in 1986 to HIV after 1994 – comes through vividly in his prints.

The exhibition invitation credits two people for awakening the political consciousness that can be traced in his art: the late actor, poet and writer Matsemela Manaka and artist and educator Sokhaya Charles Nkosi.

In 1986 Xaba enrolled at the Funda Community College in Diepkloof, Soweto, where he studied children’s art education and encountered Nkosi and Manaka, who were both working at the arts training centre.

“At Funda he met two of the most important people in his life: Charles Nkosi, who took artistic leadership at the institution, and Matsemela Manaka, who awakened in Xaba his deep-seated political awareness at the time of the state of emergency in South Africa,” according to an Art on Paper Gallery write-up on Xaba.

Funda’s legacy

At the time, a handful of art centres provided artists like Xaba with creative and political refuge – offering training across artistic disciplines at a low fee. One such institution was the Rorke’s Drift art centre in KwaZulu-Natal, which is credited with producing celebrated artists such as Sam Nhlengethwa and Azaria Mbatha. When it closed in the early 1980s, “Funda then became the answer” for black students with diminished artistic resources at their disposal.

This is what Nkosi, Funda’s fine arts department head, says as he sits at his desk in a modest office occupied by piles of papers, filing cabinets and framed artworks – most notably a piece by Funda alumnus Mbongeni Buthelezi, which hangs behind Nkosi.

“Funda was also a response to the aftermath of the 1976 student uprising in Soweto,” says Nkosi. “There was a need then to look at inculcating the importance of education or alternative education. Because kids were not going to school, a lot of them were languishing in jail and some were crossing the border to join liberation movements.”

Nkosi, a fine artist who trained at Rorke’s Drift, talks me through Funda’s history, which he has lived through since arriving at the nongovernmental organisation almost 30 years ago. “When I started here in 1986, after getting retrenched from the SABC, I found that the Funda legacy had already begun.

“One of the father figures was the late Professor Es’kia Mphahlele,” he says of the activist and writer who established links between Funda and the University of the Witwatersrand. He also mentions like artist Sydney Selepe and musician Arthur Mafokate, both of whom attended Funda. When Funda started “it was mainly workshop-based [and] we had the likes of art luminaries like Bill Ainsley coming to conduct workshops,” Nkosi says.

In the early 1980s the centre was first headed up by art educator and activist Steven Sack. Thanks to private sector funding, it was able to offer students training in theatre, visual art and music. Funda’s links to Wits and Unisa enabled aspiring artists to receive recognised qualifications.

No electricity, funding’s run dry

But since Funda’s heyday, much has changed. Private donations have run dry and the section 21 company receives limited government funding.

“Most of the funding came from the private sector because of [issues with] the government in the 1980s. But we still have funding problems. We get some funding for bursaries from the National Arts Council, which is a funding wing of the department of arts and culture,” Nkosi says. “But you can imagine how many kids would have benefited if we got [more] funding.”

On top of this, no electricity runs through the school. Funda has had no power since 2009.

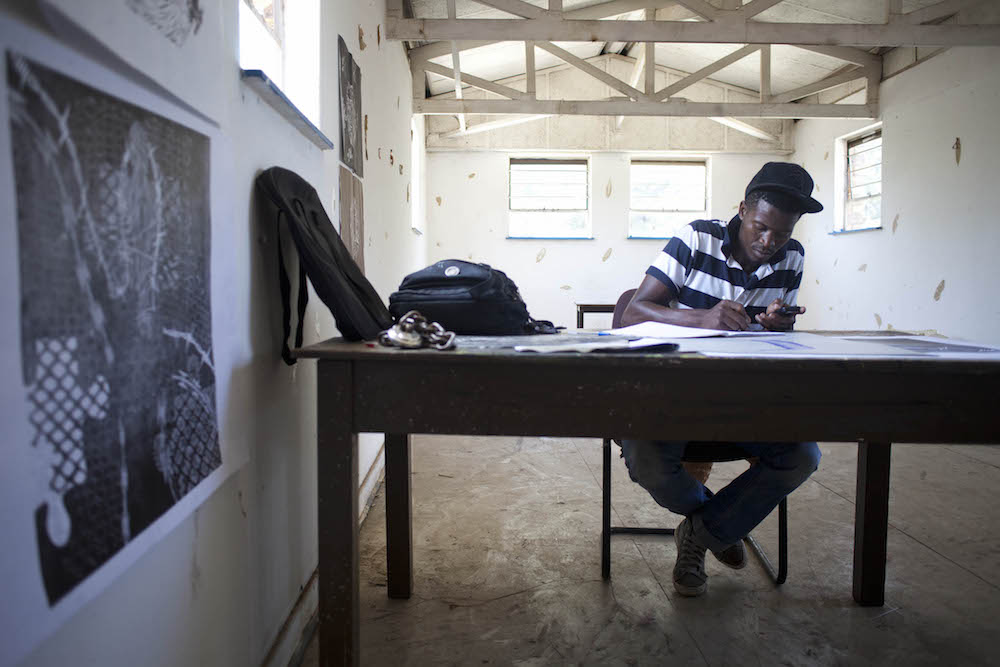

It no longer offers artistic disciplines other than visual art, and has only 12 full-time students and four teachers (including Nkosi). Most of the centre’s musical instruments have been stolen.

Adding to its woes, there have been what Nkosi describes as “people coming from outside and disturbing operations”. He is referring to the 2008 invasion of Funda’s premises by a group that calls itself the Senior Citizens Focus Co-operative.

“The Senior Citizens Focus Co-operative, acting on a directive from the mayor’s office [or rather the property wing of the municipality, the Johannesburg Property Company], seized partial control of the centre’s buildings,” Tshwane University of Technology lecturer Pfunzo Sidogi wrote in his 2011 master’s thesis on Funda. After a court case, Funda regained control of the property and partial order was restored, but the centre’s chairperson admits this incident has caused Funda to lose some of its credibility.

Motsumi Makhene – who has been at Funda for more than 30 years and was instrumental in founding the now defunct music department – says that, “administratively, everything is on track” at Funda. But, like Nkosi, he is concerned about the centre’s funding.

Future of Funda

Despite the centre being in dire financial straits, Makhene, who is also the principal of the Central Johannesburg College, speaks highly of the graduates Funda has managed to yield. “[The students] that we produce on an annual basis stand in good stead nationally and internationally. In terms of the quality and depth of expression that they have, we have alumni that are specialists in the plastic medium of art.”

The plastic or sustainable art to which Makhene refers (and for which Buthelezi is famous) is a major part of the arts education offered at the centre. On a tour around the school, Nkosi shows off an exhibition of artworks made by former Funda students from recycled goods – using materials they can afford and adopting an environmentally conscious approach.

After walking through a class filled with young artists busy with a practical lesson, Nkosi sighs quietly: “Yah, we do need intervention. But for me, I believe in one thing. When the going’s bad, you cannot imagine yourself running away from the place where you are expected to come up with remedial interventions.”

With questions hanging over the future of Funda, one wonders whether it will suffer the same fate as other fledgling and established art centres.

Concluding his thesis, Sidogi raised a point about the standard of arts education in townships almost 40 years since the Soweto uprising: “Why are things not improving, especially when considering that the arts industry in general has been on an upward trajectory over the past 15 years of democracy? Why has this trend not engulfed the township and rural parts of South Africa?”

Nhlanhla’s Open Chair runs until April 15 at Artist Proof Studio, 3?President Street, Newtown, Jo’burg

Correction: An earlier edition of this article mentions that Xaba passed away 15 years ago, instead of 12.