The last memory Maritsa Balanco (40) has of the man she loved is four men carrying his body out of the Dihlabeng Regional Hospital in Bethlehem in the Free State amid the “stench of rotten, wet bodily fluids”.

When Frik Balanco (65) died at 7am on January 29, his wife was “terrified” that his body, like others, would be left for hours lying on his bed in the intensive care unit (ICU) of Dihlabeng.

Her fears were not unfounded. During Frik’s stay in the intensive care unit, Maritsa says she often arrived at her husband’s bedside to find the bodies of patients who had died earlier in the day lying on the beds next to him, covered by blankets.

“One woman died at 1pm. When I visited my husband that evening the body was still lying there. At 9pm, when I left, they finally brought a trolley to fetch her body – eight hours after she had died.”

Maritsa told the Mail & Guardian, from her mother’s home in Standerton, to which she moved after her husband’s death, that she had “begged the nurses to immediately remove her husband’s body”, but when she returned to the hospital at 10am to collect his “death letter”, his body was still lying there. “I was in tears and didn’t know what to do. All I could think of was to call [undertakers] Avbob and pay them to come and collect him.”

When Avbob personnel arrived, there were not enough people to carry Frik’s body from the fourth floor, on which the ICU unit was, to the hearse. None of the hospital’s three lifts were working and the only way to get him to the ground floor was to take the stairs.

“There were two Avbob people, but we needed double that. We had to beg two porters to help us, but they only did so after a massive fight. My husband’s daughter [from a previous marriage] walked down the stairs with the men who carried his body. Blood and other body fluids were flowing from Frik’s body and they spilled all over the stairs on each floor. I remember people walking through it.”

Maritsa Balanco, Frik’s wife, took this photograph with her cellphone and agreed that it be published.

Old age

Maritsa was “very suspicious” when doctors informed her that her husband’s “old age” had been a major contributor to his death.

Until that morning, when Frik – a clerk at a company that manufactures trailers – was admitted to Dihlabeng, she says he had never been seriously ill.

He was about to retire. “He was a fit and healthy man. His mother is in her 80s. That’s old. Not 65.”

It was by chance that Frik ended up in the Dihlabeng hospital.

Last year Frik and Maritsa, from Ballito near Durban, were passing through Bethlehem on their way to spend some time with Maritsa’s mother in Standerton. But in the early hours of Saturday December 20, Frik suddenly experienced an “intense shooting pain” that he said felt like “gas stuck in his chest and stomach”. The Balancos could not afford medical aid and, in a panic, Maritsa asked the GPS for the closest state hospital in the area. They were directed to Dihlabeng.

She pulled the car into the parking lot outside the four-storey building and ran into the hospital in search of a doctor and a wheelchair.

“Frik could not walk at all and was too heavy for me to carry. But I quickly realised that I’d have to go and find the wheelchair myself and figure out a way of lifting him into it from the car. There was simply no one to help.”

After an hour of waiting with her husband in the casualty unit, without being attended to, Maritsa went to look for a doctor. She says Frik was eventually diagnosed with stomach ulcers and admitted to a general ward that morning. He was not seen by a doctor or a nurse until later that night, when nurses ordered security guards to escort her out of the hospital.

“When I asked a nurse why they hadn’t attended to him, she threw his hospital file to the side and told me I was in the way; they can’t work on him while I’m there,” Maritsa recalls.

Weeping, she ran to the casualty unit and asked a doctor to assist her husband, who put him on a drip.

“My husband was in so much pain. He couldn’t sit up straight; he could also not lie. Someone had to hold him up straight in his bed, but I wasn’t allowed to do it after visiting hours. And there was no one else to help.”

What Maritsa didn’t know at the time was that she had taken her husband to a hospital in a severe financial crisis, and that had only about half the medical officers required to run a 24-hour service, according to doctors at Dihlabeng.

It was also a hospital that regularly ran out of medication, including the medicine that would probably have saved her husband’s life.

S.O.S

In January, desperate specialist doctors at Dihlabeng sent a letter to Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi.

In it they complained that only eight medical officers were employed at the hospital in February, down from 10 in December. This week, a group of Dihlabeng’s doctors told the M&G that the hospital needs at least 18 full-time general practitioners to provide service to patients on a 24-hour basis.

“Over the Christmas period, when my husband was in Dihlabeng hospital, there were most likely fewer than 10 doctors there,” says Maritsa. “I guess they were all on leave because there was rarely a doctor on duty that I could speak to. And I remember the ones who were there were constantly out of breath because, often, all the lifts were broken. They had to constantly run up and down the stairs. There was just no way they could get to everyone.”

Frik was eventually admitted to one of Dihlabeng’s five ICU beds and put on a ventilator. Doctors then told Maritsa he had acquired a “hospital- acquired bacterial infection” and had developed a type of pneumonia that was resistant to ordinary antibiotics.

“The nurses told me the type of antibiotics that my husband needed was too expensive for the hospital to buy,” she recalls. “The antibiotics that they did give him simply didn’t work.

“Frik’s protein levels were also dangerously low and, as he wasn’t able to take food in orally, he needed intravenous feeding. But the hospital didn’t have any of the intravenous feeding in stock. Instead, they told me that ‘it’s okay to be without food for two or three days’.”

Stock outs

The M&G this week spoke to several Dihlabeng doctors on condition that their names were not revealed. They confirmed that at the time of Frik’s admission, the hospital had run out of the type of antibiotics needed to treat his pneumonia and that Dihlabeng also regularly runs out of “total parenteral nutrition”, the substance required to feed patients intravenously through a drip.

When medical personnel decided to “rinse” Frik’s lungs, so that “pus” could be removed, they faced another challenge: the hospital had no Betadine antiseptic solution in stock, the essential medication required for this procedure.

Maritsa drove to Bethlehem’s private hospital and bought the Betadine solution. She says she gave nurses the Betadine solution at eight in the morning, but when she got to Dihlabeng that evening, the procedure had still not been performed on her husband. “First, the lifts weren’t working, so they couldn’t get my husband from the fourth floor to the first floor, where the theatre is. Then there wasn’t someone available to do the procedure, or the theatre itself wasn’t available.”

Maritsa says, according to her husband’s post-mortem report, he died of pneumonia, among other conditions. There is no mention of stomach ulcers.

She remains confused and traumatised. “The hospital killed him. They didn’t have the treatment he needed or the staff to see to him. If they had, he would have been alive today.”

After Frik’s death, Maritsa says she was denied access to his hospital file. She has since applied for access through a lawyer. “I’m just waiting for that file then I’m taking the hospital to court. There’s a case of medical negligence here.”

Back at Dihlabeng, doctors told the M&G that most of them were planning to leave their positions at the hospital “as soon as possible”.

“We can’t tell patients the real reason why we can’t help them. We can’t tell them there’s a lack of staff and medication and no will from the provincial health department to fix it. We are obliged to be loyal to our employer. We just tell patients ‘we unfortunately can’t do anything more for you’. It’s bad to say, but we don’t go into detail. It’s better that way.”

Maritsa Balanco’s husband, Frik, died at the Dihlabeng Regional Hospital in Bethlehem.

Maritsa Balanco’s husband, Frik, died at the Dihlabeng Regional Hospital in Bethlehem.

Desperately seeking intervention

Doctors at Dihlabeng have now turned to Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi in desperation to save the hospital’s services from “collapsing”.

They say the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) could revoke its status as a training hospital and they need to be protected from losing their licences because of the “illegal decisions” they are forced to take because of chronic understaffing.

Dihlabeng has virtually no permanent leadership. According to several doctors, the hospital’s chief executive officer has been in an acting capacity for four years, the nursing manager for a year and the head of administration, who also works as Dihlabeng’s human resources manager, for 18 months.

Its clinical manager resigned in February “due to a lack of support from head office [in Bloemfontein]”. Her duties were transferred to a medical officer already working at the hospital. All the acting managers perform their extra responsibilities in addition to doing their normal shifts and without additional compensation.

On January 19, five Dihlabeng specialist doctors – the heads of orthopaedics, internal medicine, anaesthetics, general surgery and ophthalmology – sent a letter to Motsoaledi declaring that they could no longer “provide an adequate or safe [24-hour] health service”.

Dihlabeng is a secondary or level two hospital, with 140 beds. It serves as a specialist referral facility for five district hospitals in the Thabo Mofutsanyana municipality, one of the health department’s pilot districts for its national health insurance (NHI) scheme.

According to the Health Systems Trust’s district health barometer, only 6.1% of Thabo Mofutsanyana residents have medical scheme coverage. All others depend on public healthcare services.

Staff shortage

In their letter to Motsoaledi, the doctors list 21 general practitioners who were employed by Dihlabeng in January 2012. By February this year, only eight remained.

As of this week, four medical officers with overtime contracts are left, four times fewer than the 18 permanently employed medical officers the doctors say are needed to run a 24-hour service.

“When a doctor resigns, he or she simply doesn’t get replaced,” one doctor said. “Last year, nine medical officers applied for a position at Dihlabeng, but none of their applications was approved within two months and all found work elsewhere, mostly in other provinces.”

The Dihlabeng doctors say they are worried that Motsoaledi “doesn’t have a clue” about what is actually happening in the Free State. One said: “Health MEC Benny Malakoane is telling him lies; he’s telling him how well the system works.”

In January nine nurses resigned from Dihlabeng, and three more have quit in the past two weeks.

“It’s a chain reaction to the horrific circumstances we’re working under,” another doctor said. “It’s no longer possible to cope. That’s why we have decided to speak about this, even though we risk losing our jobs for doing so.”

According to the doctors, five community service medical officer posts were “removed” from Dihlabeng and the hospital is currently “borrowing” six community service doctors from other hospitals.

But they maintain this is still not adequate to provide proper healthcare.

Medicolegal implications

“It means that medical interns [who have completed their studies but are not yet registered doctors] give anaesthesia unsupervised or are left alone to run casualty wards without any supervision,” one doctor said.

In their letter, the specialists raise their concerns about the “vast medicolegal” implications of the “crisis” at Dihlabeng: “We are risking our careers, as well as the careers of all our doctors,” they warn.

One doctor, who plans to resign as soon as possible, said: “It’s illegal for an intern to be left unsupervised. If I’m the medical officer in charge and I assign an intern to do anaesthesia because there is no one else to do so, and something goes wrong, the HPCSA will say: ‘Sorry, you’ve taken a risk that you’re not supposed to have taken’. My licence could be revoked.

“Furthermore, if the HPCSA pays our hospital a surprise visit and finds interns working unsupervised, Dihlabeng risks losing its accreditation as a training hospital.”

The radiographers’ overtime has been capped because of provincial budget constraints and Dihlabeng cannot provide an x-ray service after 8pm, the doctors claim.

“The doctors on call are making decisions on a clinical basis that requires radiological investigation. Central lines [specialised drips inserted deep into the neck vein] and intubations [a tube placed in a patient’s airway in order to ventilate] cannot be confirmed to be correctly placed. We believe that doctors will not be covered if they’re investigated by the HPCSA,” the doctors told Motsoaledi in their letter.

Budget constrains

Earlier this month, five severely injured patients were admitted to Dihlabeng late at night. One GP said: “Doctors literally guessed which parts of their bodies had fractures and treated them according to their guesses, as there was no one to perform x-rays. If something goes wrong, those patients will be able to sue us. This is a terrible situation on many levels.”

Moreover, because of budget constraints the doctors say they can only perform emergency surgery at the hospital and elective surgery – not for life-threatening ailments – has therefore been put on hold.

One said: “I recently had to put a patient in her fifties on disability pension because she can no longer see. All she needs is a simple cataract operation. But we can’t give it to her. Instead, we had to sign her disability application form. She will get about R1 500 a month, about the same amount as the cost of a cataract operation. But a cataract operation will be a once-off cost; the disability pension will be ongoing. These are the calls we are forced to make.”

According to the doctors, they have tried to set up meetings with MEC Malakoane five times in the past two years and have also written to him, but have never received a response.

In January, the doctors say, they tried to approach the provincial health department’s chief operating officer, Balekile Mzangwa, for “some guidance as to the way forward”.

“But he could not be reached because he had joined Premier [Ace] Magashule on a trip to Cuba … We have found out the Cuba trip included an entourage of 72 people at a cost of about R21-million. The head of department, David Motau, was in Germany for some reason and could also not be reached. Malakoane himself was not available because he was appearing in court on corruption charges.”

Malakoane is charged with corruption, fraud and money laundering dating back to his tenure as municipal manager of the Matjhabeng municipality in Welkom between 2007 and 2010. He and seven others, including the Free State’s arts, culture and recreation MEC, Nkowanje Leeto, who was the municipality’s executive mayor at the time, are accused of receiving kickbacks worth about R13-million for “irregularly awarded” contracts.

In a press release, the Free State government confirmed the delegation’s Cuba visit but refused to reveal the cost of the 15-day trip. According to the statement, criticism of the visit is “politically motivated” as the Democratic Alliance has initiated an inquiry into it. Health delegates were included in the trip as it was the provincial government’s duty to “motivate” and “encourage” 197 Free State students studying medicine in Cuba to ensure their return “to the Free State province upon completion of their studies to ensure that we continue to derive benefit from this investment”.

But a Dihlabeng doctor asked: “How can you run a department like that? According to the DA’s statement, the cost of the trip worked out to about R300 000 per person. That’s more than R20 000 per person per day. How is it possible to have the money for such a trip for several health department people but not for doctors’ or nurses’ salaries, or for patients’ medication?”

Rotten apple

Doctors say “everything was fine at Dihlabeng” until Malakoane became MEC in March 2013. “That’s when the corruption and mismanagement started, the medication started to run out and our staff got smaller and smaller,” one said. “We didn’t complain five years ago.”

In 2011 the Free State government awarded Dihlabeng for being the best regional hospital in the province. But Malakoane’s spokesperson, Mondli Mvambi, accused Dihlabeng’s doctors of having a hidden agenda.

“This is clearly a political statement that we do not think can be made by doctors independently without any political influence from some other interests elsewhere. It is not the work of doctors to judge the performance of the MEC. The head of the department is the one who works directly with facilities. It is inconceivable and outrageous that such an allegation can be made.”

Mvambi also referred to Free State doctors’ criticism of Malakoane in a letter published in the media in February as “a deliberate campaign to undermine his leadership by people who regard themselves as untouchable”.

In a response to the Mail & Guardian‘s questions about the Dihlabeng doctors’ letter, Motsoaledi’s spokesperson, Joe Maila, said: “I can confirm that the office of the ministry has received the letter. The letter outlines a number of allegations which we believe are serious. The national health department will work closely with the province to find solutions faced by … Dihlabeng. It is in our interest to get the public health sector to work.”

But, two months later, the doctors say Motsoaledi has not responded to any of their concerns and they are beginning to lose faith in him.

Party politics

One Dihlabeng doctor said: “The political reality seems to be that Ace Magashule and Benny Malakoane are higher up in the ANC ranks than Motsoaledi. Why Motsoaledi is in his position if he doesn’t have any political influence over the quality of health in provinces, I don’t know.

“I believe the health minister is worried about Dihlabeng, but it seems like there’s nothing he’s able to do about it. We and the people here are on our own.”

This week waste removal stopped at Dihlabeng because the removal company has not been paid. According to doctors, this has brought about an infestation of rats at the hospital’s waste dump.

The rodents have also begun to venture into the hospital itself.

Ants and termites are also infesting some of the primary healthcare clinics in the area because the hospital’s pest control contract has been terminated.

On Thursday morning, a Dihlabeng doctor called the M&G to report that representatives from the national health department and the Office of Health Standards Compliance had been “hanging around” at Dihlabeng after the newspaper’s inquiries were put to the department this week.

But for Maritsa Balanco it wouldn’t bring back her husband.

“Politics,” she says, “does not matter to me. I don’t understand much of it at all. But what I do understand, is that it killed my husband.”

If you have had a bad experience at a hospital, please share it with us on [email protected]

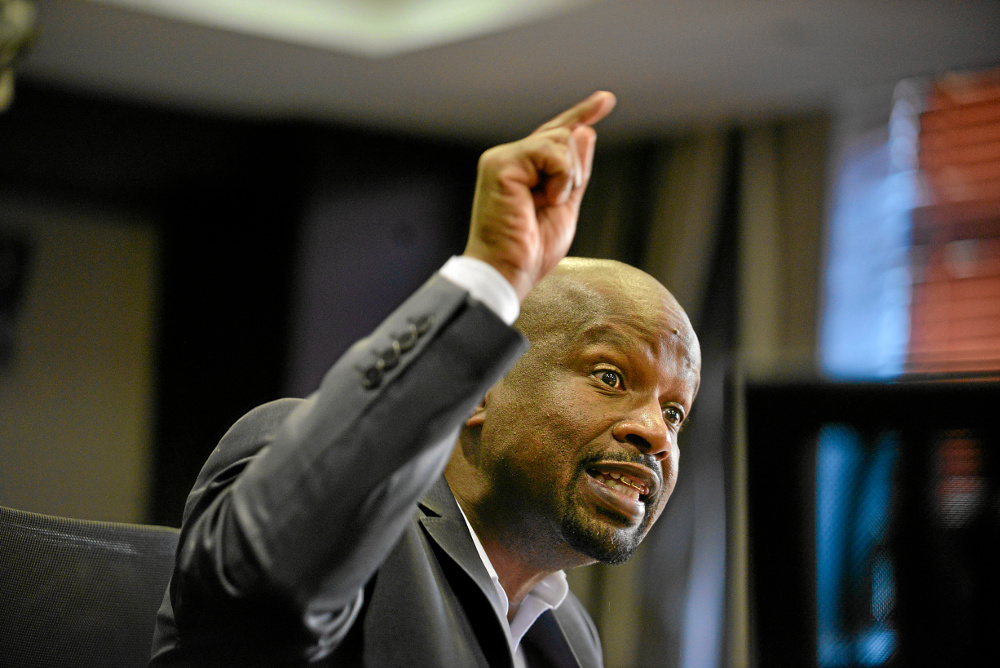

Target of anger: The doctors blame Free State health MEC Benny Malakoane for the crisis.

Target of anger: The doctors blame Free State health MEC Benny Malakoane for the crisis.

‘Free State killing NHI dream’

Last week Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi warned during the Medico Legal Summit in Centurion that medical negligence claims at public hospitals have reached a crisis point where government institutions have been left bankrupt.

“We are aware that some hospital chief executives are not doing anything to safeguard the welfare of patients but instead deliberately jeopardise the welfare of patients and immediately report the legal members … to start litigation,” he said.

But, according to doctors at Dihlabeng, there is another “side to this coin” in the Free State.

One doctor said: “I agree with Motsoaledi that there’s a problem with negligence claims. But at a hospital like ours, and many other Free State hospitals, so many things go wrong that if lawyers started to hang out in the hospital, almost every patient will have something to sue for. There are just too many gaps.”

In a letter that Free State doctors released to the media in February, they claim the provincial health department owes R600-million in malpractice suits, which “Premier [Ace] Magashule blames on doctors”.

But Mvambi denied this and said this is incorrect. He said the department only faces claims of R673 373 for the 2013/2014 financial year.

By last year, the Free State health department racked up R700-million in debt, dating back to the department’s financial crisis in 2008-2009. In July Motsoaledi intervened and sent a national health department team to help realign up to R40-million of the Free State’s budget to ensure payments to drug companies and to fix and maintain boilers and other equipment at hospitals.

Shortly afterwards, the health department was placed under the administration of the provincial treasury. But Malakoane said the transfer of financial authority was “self-imposed”.

Dihlabeng’s doctors allege the hospital’s services are about to breakdown due to “Malakoane’s mismanagement”.

“The Free State health department is killing the health minister’s dream of a National Health Insurance scheme minute by minute. That’s how strong I’m feeling about this,” a doctor said.

Mvambi, responded: ” They [the MEC’s financial turn-around strategy’s targets] have been met to the surprise, denial and disbelief of many prophets of doom that continue to describe our system as dysfunctional and collapsing.”

Who suffers when Dihlabeng runs out of equipment

Doctors at Dihlabeng Regional Hospital told the Mail & Guardian that the hospital regularly runs out of the following consumables. We asked them about the implications:

• Colostomy bags (a bag patients need to collect their stools following colostomy, which makes an opening for the bowels through the abdomen)

“For a patient it’s humiliating, because it means their stools are running out on their abdomens without a bag.

“Can you imagine faeces running out of a hole in your abdomen? Some of our patients use Checkers bags, because we often can’t provide them with colostomy bags. Without a bag, they can’t leave home.”

• Tru-cut biopsy needles (used to do prostate cancer biopsies on men)

“When we don’t have tru-cut needles, we can’t remove tissue to determine if a man has prostate cancer.

“This week, we have about 10 needles left. That’s supply for about one to two weeks. We often ask patients to buy their own needles from elsewhere and bring it to us so that we can perform the procedure. But few have money to do so.”

According to the National Cancer Registry, prostate cancer is the most common cancer in black South African men and the second-most common cancer in white men.

• ECG, CTG papers, prescription charts

“When we don’t have ECG paper, we can’t diagnose heart problems. We, for instance, won’t know if someone has had a heart attack. Without CTG papers, we can’t monitor a fetus, so we wouldn’t know if a baby is experiencing distress in a woman’s uterus. At the moment, we can’t print prescription charts for patients to collect their prescriptions with, because we don’t have ink for our printers. We can’t write it on any piece of paper, because a prescription chart is a legal document.”

• Spectacles and lenses

“We have a waiting list of 300 patients for spectacles. Our optician has tested their eyes. We know what strength lenses they need, but we can’t give them glasses, because we don’t have frames and lenses.”