Wrestling with values: Photographer Zanele Muholi with works from her acclaimed series Faces and Phases.

South African contemporary artists are becoming increasingly popular abroad and are fast gaining a reputation as “global rock stars”.

Some South African galleries say they have noted growing international interest in the work of local artists. Auction houses also say that because of the demand, art has become a viable occupation for artists across Africa.

Although works by Irma Stern and Gerard Sekoto are still considered key investments, younger contemporary artists are also gaining traction.

“Artists like Zanele Muholi are now global rock stars,” said Joost Bosland, one of the directors of the Stevenson Gallery.”Her travel schedule is more demanding than any other artist we have.”

Bosland said he is loath to use the term “up-and-coming” as it takes away from the fact that artists often have to work hard for years before their careers flourish.

Muholi is known for her activist and artistic work that centres on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) community. “Zanele has been working so hard and she has been unrelenting. Now her career is blossoming,” said Bosland.

Muholi, from Durban, has been shortlisted for the 2015 Deutsche Börse photography prize for her publication Faces and Phases. Bosland said international interest has been growing in individual South African artists rather than in South African art as a whole.

Prices skyrocketed

Goodman Gallery spokesperson Matthew Krouse said that he too has seen a heightened demand for local contemporary artists, and that there has been international interest in some of the new talent the gallery has worked with. “Some of the key artists have done exceptionally well, where prices for their artwork have skyrocketed,” he said, citing works by the Essop brothers – Hasan and Husain – who have even sold work to Elton John.

Speaking from Paris, Muholi said the international interest in her work means that the voices of the black LGBTI community are finally “being heard”.

At the moment, Muholi is participating in a group exhibition called Residual: Traces of the Black Body as part of the Format International Photography Festival at the University of Derby in the United Kingdom. She stressed that her work and her success is less about “Zanele” and more about her “extended queer family” who have enabled her to tell the South African story through different eyes.

She said her photographs of the LGBTI community are about capturing images that she didn’t see as a child. She hopes to pave the way for other artists. “We are writing our history in a new way, specifically regarding our queer history,” said Muholi.

The managing director of auction house Strauss and Co, Stephan Welz, said there are several local artists whose careers are “blossoming” and that respected galleries play a “huge role” in bringing emerging artists to the fore.

“There is a new moneyed class who can afford to buy art,” he said, adding that most artworks are sold to individuals rather than to corporates or institutions. “I think the trend will continue and we will see a few more contemporary artists blossoming. At the moment, the South African market is largely centred around some 30 artists.”

Fine art auction house Bonhams said the South African art market is in the midst of a “revolution” thanks to increasing interest from international audiences. But although new contemporary artists are making an impact on the global stage, the “old-school Irma Sterns” are still a firm favourite.

“This revolution or renaissance [in African and South African art] is bringing hope to communities in many of the 54 countries that make up the patchwork quilt of Africa,” said Giles Peppiatt, director of African art at Bonhams, which has a department dedicated to sales of South African art.

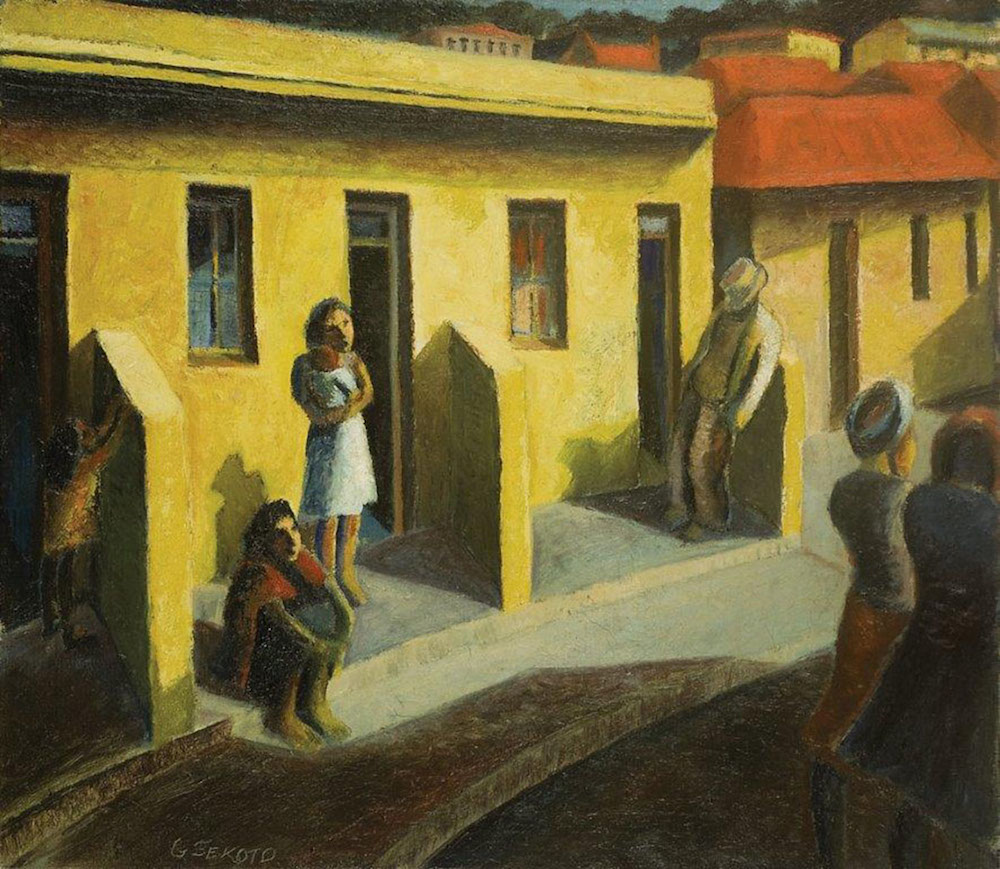

Gerard Sekoto’s Yellow Houses, District Six

He said the “tussle” for African and South African art on the global stage is making art a “viable occupation for artists across Africa”.

World records

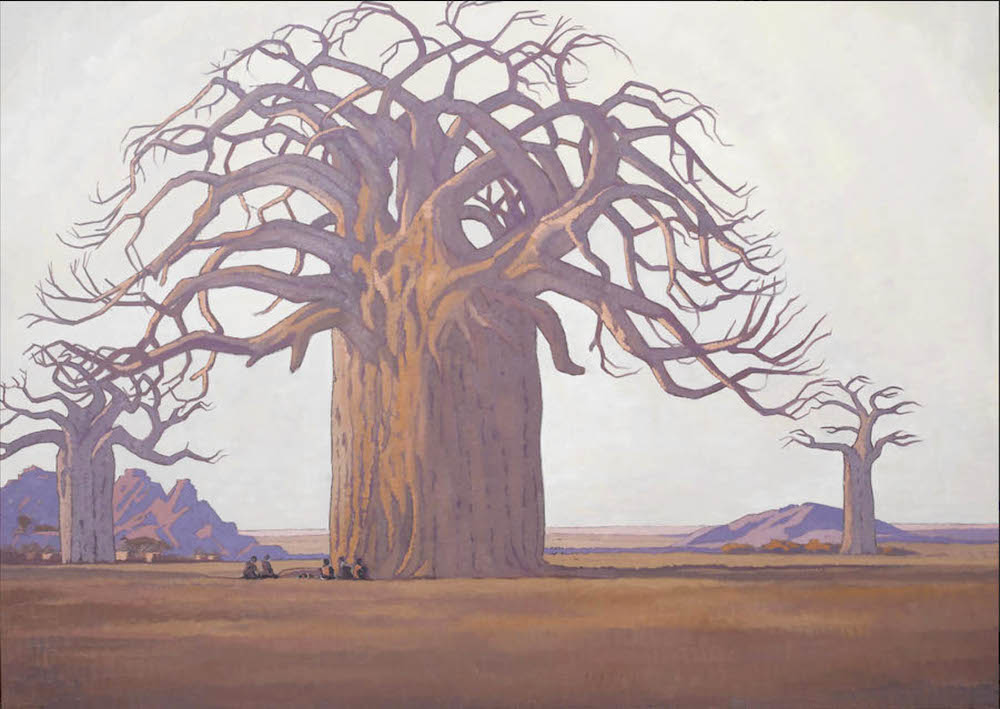

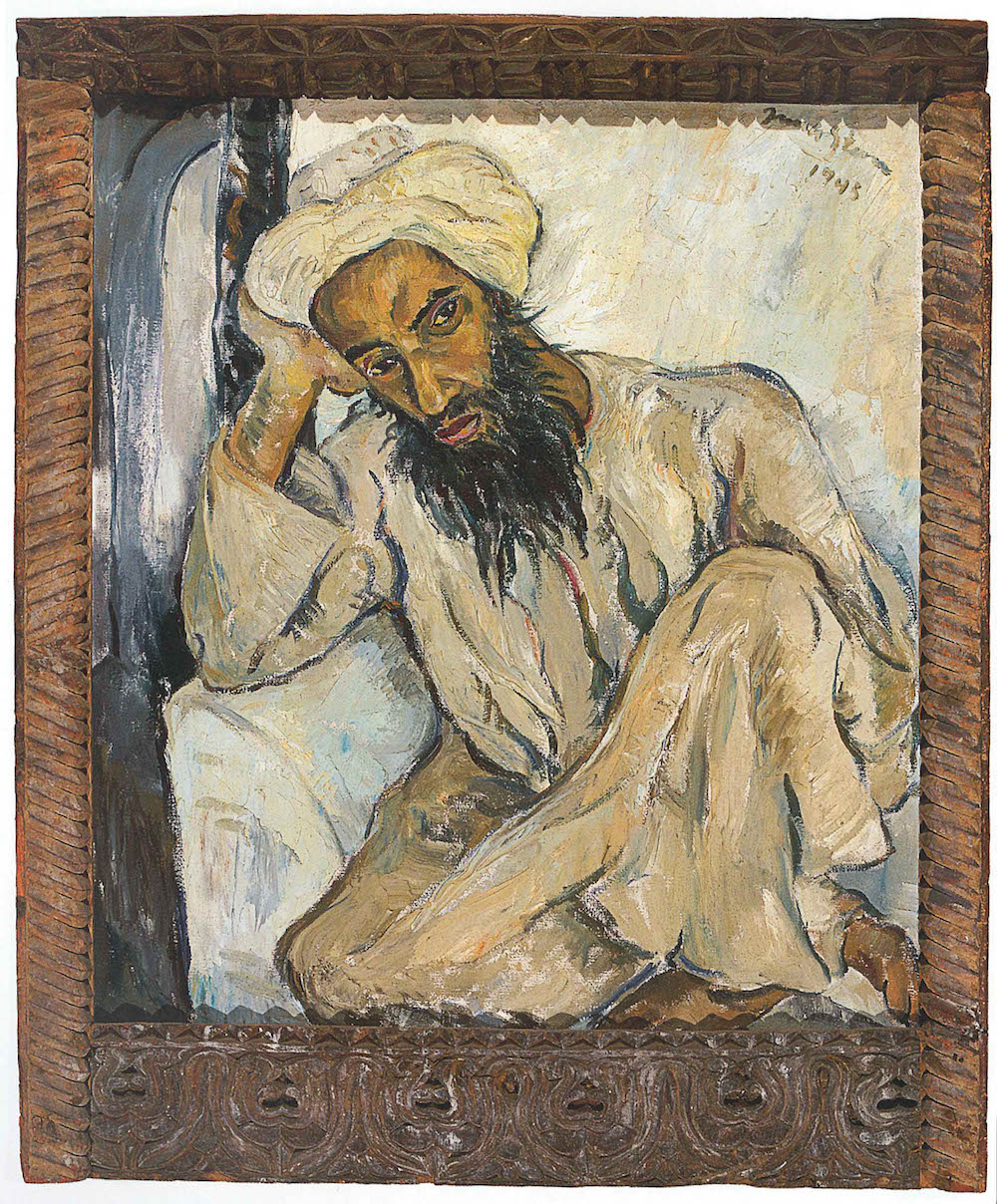

Bonhams has set world records for the sale of artworks by South African artists, most notably the sale of Stern’s Arab Priest to a Qatari museum for R34-million. It also sold Gerard Sekoto’s Yellow Houses, District Six for about R10-million and Pierneef’s The Baobab Tree for about R14-million.

Peppiatt said when Bonhams first ventured into the South African market in 2007 by chance, it originally priced a Sekoto painting at £20 000. Instead, it sold for more than £120 000.

“You might say it was a lightbulb moment. The thought came to us that just maybe the time had come to create a stand-alone sale for South African art, the first of its kind outside South Africa.” The decision, he said, paid off immediately and has piqued such interest that Bonhams now hosts three South African art auctions in London every year.

“As we promoted this art, the art market responded strongly and soon the auctions were grossing £10-million,” he said.

JH Pierneef’s Baobab Tree

“How is it that works by Irma Stern, which sold for figures around £100 000 maximum 10 years ago, now go for millions? How is it that [Vladimir] Tretchikoff, who was seen as an embarrassment and a mark of kitsch taste, is now selling for hundreds of thousands and Gerard Sekoto, who fled the country to die in poverty in Paris, has works that make hundreds of thousands too?”

The answer, he said, is that modern and contemporary African art is “one of the hottest properties on the art block.

“Africa is the new China when it comes to art. When the Tate, the Smithsonian and other similar institutions start putting on exhibitions of contemporary African art, then one knows that something strange and wonderful has occurred and that real change is in the air,” said Peppiatt.

The auction house has also decided to take on modern and contemporary art from the rest of Africa. An “Africa Now” sale is held every year in London or New York.

Increasing interest

Christopher Peter is the director of the University of Cape Town’s Irma Stern Museum, which is located in the house where Stern once lived in Rondebosch. He has worked at the museum for more than 35 years and says he has observed an increasing interest in Stern’s work from foreign visitors.

“Irma has always been everyone’s favourite: the Picasso of Africa. I have seen increasing interest over the last couple of years, with an extended interest that goes beyond South Africa.”

He said the museum – where some of the rooms have been left precisely as Stern arranged them – has helped to nurture the global interest. “Tourists definitely want to know more. Irma had a controversial start. She was upfront avant-garde but came into her stride in the 1930s before becoming the high priestess of South African art.”

Irma Stern’s Arab Priest (detail)

The work of Sekoto – a black South African artist and jazz musician who died in exile in Paris – has also gained an avid following. One of the trustees at the Gerard Sekoto Foundation, Barbara Lindop, said there is a new appreciation for works by black artists.

She said, in 1987, Sekoto’s work would have sold for R6 000. Now one of his paintings fetches up to R7-million.

“Apartheid held back the value and appreciation of black art, but it wasn’t until the end of apartheid that black art was really appreciated and looked at. Now it’s huge. The whole world is talking about it,” said Lindop.

Thenjiwe Nkosi recently became a full-time artist. (Madelene Cronjé)

Food-chain dynamics colour the difficult career of a full-time artist

So just how viable is it to be an artist in South Africa?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi has been an artist for 10 years, but has only recently been able to work full time. She said although the art industry in South Africa is small, she’s had international interest in her work.

Nkosi said black women are often not given the scope they deserve. “I think women of colour tend to be marginalised. I’d like to see more black and brown women represented in the industry.”

Senzeni Marasela, who has been an artist for 15 years, said many local artists lack business skills. “Artists tend to be at the bottom of the food chain, but we are the ones who make it work.”

She said the “boom” in international interest in local art is largely owed to the increased number of visitors to South Africa. Events such as the London Art Fair have also helped South African and African artists to gain exposure, Marasela added.

Historical document

“I think a lot of international galleries will eventually open up galleries here too. All artists reflect what is going on around them. Artworks remain a historical document – a marker of a particular time.”

But the nature of art on the continent is also changing, said Marasela. “It has become far broader than it used to be. Performance art is growing; film is growing. These things that used to be alien to the fine arts are now gaining traction.”

Hermann Niebuhr has been a full-time painter since 1997. He singled out Cape Town as the “go-to destination” in the local art scene. “Cape Town seems to have become a little country on its own in the art market; before, it used to be the second cousin of Jo’burg.”

He said although people are quick to label works out of Africa as “African art”, this does not mean that African artists don’t also find inspiration beyond Africa’s borders.

“African art is maturing. It’s become less about commentary and activism and has become part of the global conversation. That kind of DNA [commentary and activism] is built into South African artists.” Niebuhr added that not enough is being done to nurture young artists; although it is a viable career, it is “difficult”.

“Artists need to eat, they need to pay the rent, they need to pay taxes. Often you have to produce work for galleries that cater to their clientele – largely the white middle class. “The emerging black middle class still seems nervous about purchasing art. It’s the ecosystem artists find themselves in – how do you make work you can live off without being pigeonholed?”

Niebuhr would like to see the creation of “hubs”, using empty buildings as a place for young artists to “knock about”. “Subsidising an artist’s space by giving them somewhere to work could help,” said Niebuhr. “It’s been an interesting journey, but I know what it’s like to be poor.” – A’Eysha Kassiem