NEWS ANALYSIS

Earlier this month, when President Jacob Zuma said that teenage mothers should be separated from their children and sent “far away” to Robben Island where they would be “forced to go to school”, even he forecast a backlash. “I am sure people are going to protest as I am talking now,” he said.

Sure enough, the Democratic Alliance and nongovernmental organisation Sonke Gender Justice called on Zuma to retract his statement. But, beyond them, there was no strong voice of damning dissent, raising the question: Where was the mainstream feminist reaction to this view?

As usual the ANC Women’s League failed to pipe up. “Predictable”, some might say, but when the organisation claiming to represent “the progressive women’s movement” says nothing, where does this leave South Africans in their bid to confront sexism?

When Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron told MP Angela Eagle to “calm down, dear” in 2011, the clamour for him to apologise was fierce. Politicians, mainstream media and activist organisations berated Cameron for being “sexist, patronising, insulting and un-prime ministerial”. Seizing on Cameron’s slip, feminist organisations lobbied Parliament and universities staged “reclaim the night” protests – cleverly appropriating the phrase “calm down, dear” as a slogan to challenge sexism in society.

When blatantly sexist comments from political leaders go unchallenged in popular discourse, it provides a context for sexism to play out – unremarked – in the everyday spheres of business and the home. On the one hand, South Africa is a world leader when it comes to gender equality, boasting close to 50% female representation in Parliament.

Yet inside the home and around the dinner table it is a different story. Recently, I attended a dinner party in Johannesburg where men sat while women served. When I suggested a man also get up and help, I was told to “ease up” on “always trying to be a woman’s libber”. The attack drove home one of the most revealing statements to have emerged from a parliamentarian since 1994: “Democracy stops at my front door.”

Marginal support: The Black Sash, a nonviolent white women’s resistance organisation, prioritised race issues. (Gallo Images/Rapport archives)

What has happened to the feminist voice in South Africa? It’s not as if issues have gone away. Femicide happens daily and our rape statistics are among the highest in the world.

For Mary Burton, former president of the Black Sash anti-apartheid women’s movement, this is the question on many feminists’ lips but no one is articulating it. Burton laments: “I get calls from ex-Black Sash members suggesting we don our sashes and take to the streets again, but it doesn’t seem right. There needs to be a new movement.”

According to Shahana Rasool, a lecturer in social work and domestic violence at the University of Johannesburg: “Feminism has never been something the average South African woman aspires to.” Indeed, even at the height of the Black Sash a marginal percentage of women were affiliated with the group, which was itself ambivalent towards the label and put fighting race issues first. “It has never been fashionable,” Rasool said, “because many people don’t understand what feminism is and reject the label out of fear they will be branded man-haters”.

Rasool sees a solution in education: “We need to destigmatise the word through strategies to make feminism more palatable. This means educating people well before university level on the achievements of feminism, such as the vote and abortion rights, which are taken for granted.”

It perhaps hasn’t helped that there’s been a tendency to use feminism to cover all liberal bases. To groups like Sonke Gender Justice, feminism incorporates “issues affecting women, black people, people with disabilities and queer people”. Their consultant, Sisonke Msimang, said “it is crucial to use the term ‘feminism’ to address all the forms of oppression that we see in South Africa today”.

This broadening of the canvas has had benefits, bringing the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender fight into the feminist camp. Activists such as photographer Zanele Muholi have breathed new life into South African feminism, extending the cause to cross-gender and sexuality rights. But, for the feminist label to carry every injustice, the cause runs the risk of losing focus. This is especially dangerous in South Africa where issues around race and class have tended to take a front seat on the political and social agenda.

Gender activist and academic Lisa Vetten agrees with Rasool that “feminism never grew deep, broad roots in South Africa”. For Vetten, things have gone backwards in the past 15 years with feminism being labelled “un-African”. She identifies Zuma’s rape trial in 2006 as a significant turning point because “it opened up and legitimated social conservatism”.

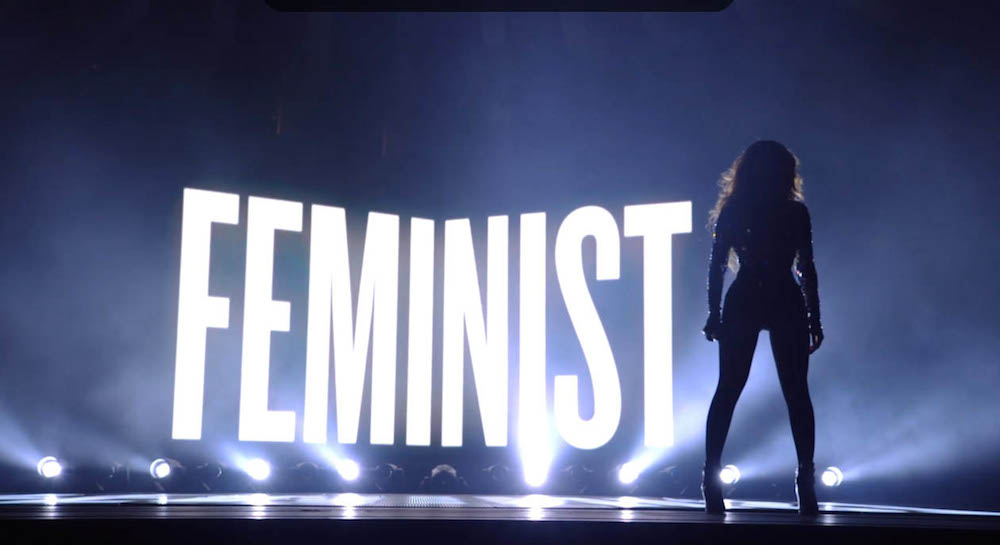

Surprisingly, Vetten warns against the initiative to mainstream feminism, because she sees it as “dumbing it down” and “divesting it of more challenging content”. Mainstreaming feminism can be diluting, as seen in the shallow “girl power” branding strategies adopted by pop artists such as the Spice Girls and Beyoncé.

In 2013, Beyoncé described herself as a ‘modern-day feminist’. She takes on the label unapologetically but muddles its message by promoting stereotypical images of body and sexuality. (MTV)

Yet there are also clear advantages to mainstreaming feminism. When Caitlin Moran, a columnist for the Times in Britain and author of How to Be a Woman (2012), said “We need to reclaim the word feminism”, she simplified the question “Am I a feminist?” by suggesting a straightforward way to work it out: “Put your hand in your pants. a) Do you have a vagina? and b) Do you want to be in charge of it? If you said ‘yes’ to both, then congratulations! You’re a feminist.” Using wit, Moran makes the decision easy and logical.

In South Africa’s mainstream media, bold or humorous feminist voices are few and far between. They can be found in the blogosphere where there is an attempt, on sites such as Talking Heads, to revolutionise the way African women talk about sex. But blogging is not enough.

Perhaps a first step to extending the fight is simply and directly to “call out” sexism. This is the view of Sakina Mohamed, acting executive director of Powa (People Opposing Women Abuse), who said: “If we do that people will see that sexism is not okay. They will fear a clamour of women at their door.”

Driving to work recently, I was listening to John Robbie on 702 when I heard him ridicule an article that suggested that holding the door open for a woman is an expression of “benevolent sexism” that masquerades as respect, but in reality treats woman as the weaker sex. Robbie invited listeners to call in to “call out the BS” in this claim, which he saw as an attempt to pit men as the enemy who can do no right. He seemed, perhaps unwittingly, to create a platform for chauvinist “banter”.

With rising frustration, I rolled down my window and yelled “feminist!” into the morning traffic. It seemed pointless – a shout into the void – though, I confess, it made me feel a little better.

I sat there thinking of all the times I’ve let sexism slide. “Okay,” I thought, “note to self: must do better. Time to invoke the power of Powa. The buck stops here.”

Feminist groups outside South Africa

The Pragmatists:

Everyday Sexism Project

What they do: Founded in 2012, this website gives a platform to document daily experiences of sexism “so niggling and normalised that you don’t even feel able to protest”.

Where: Britain, with contributors from 15 countries, including South Africa.

Known for: Providing a support network for calling out offensive “banter” and breaking the silence on sexism.

UK Feminista

What they do: Founded in 2010, this organisation provides training and resources for gender activists and groups to arrange campaigns and events.

Where: Britain

Known for: Leading protests against women’s portrayal as “sex objects” and campaigning for supermarkets to “lose the lads’ mags”.

The Radicals:

Sextremist: An activist of radical feminist group Femen at a protest in Kiev. (Valentyn Ogirenko/Reuters)

FEMEN

What they do: Founded in 2008, this protest group developed “sextremist” strategies to achieve “complete victory over patriarchy”. The movement sees the reclaiming of women’s bodies as tantamount to female liberation.

Where: Ukraine, headquarters Paris

Known for: Topless protests against sex tourism.

Pussy Riot

What they do: Founded in 2011, this punk-rock protest group stages guerrilla performances in controversial public spaces to voice opposition to the conservative values of President Vladimir Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Where: Russia

Known for: The arrest of three group members in 2012 for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” after staging a protest in a church, which resulted in two years’ imprisonment for two members.

Feminist groups in South Africa

Powa (People Opposing Women Abuse)

What they do: Formed in 1979 and based in Johannesburg, this women’s rights organisation provides shelter to survivors of abuse and works to advance women’s rights.

Known for: The first organisation to establish a shelter for abused women (in 1981). Today, it is considered an expert organisation on issues of domestic violence.

One in Nine Campaign

What they do: Formed in 2006, this collective bases its name on a 2005 Medical Research Council study that indicated that just one in nine rape survivors report to the police. They support survivors in the process of reporting crimes and seeking justice through the legal system.

Known for: It was formed in support of the woman who brought a rape charge against President Jacob Zuma in 2006.

Global movement

HeForShe campaign

What they do: Formed in 2014, this solidarity campaign was established by UN Women to combat feminism’s man-hating reputation by involving men in the fight for gender equality and inviting them to take a HeForShe pledge to the cause.

Known for: The campaign mobilised 100 000 men in three days. It has attracted celebrity support, including President Barack Obama and actor Emma Watson, who is the ambassador for the campaign. It aims to involve one million men by July 2015.