The poo'ed Rhodes statue.

Am I the only one who feels ambivalent over the demand that the Cecil John Rhodes statue be taken down at the University of Cape Town?

Ever since UCT student Chumani Maxwele flung excrement at the statue, it has sparked a raging debate to remove the statue, with those on the side of removal campaigning together under the collective “Rhodes Must Fall”. Those against the removal use problematic “historical” justifications and moral relativism that I’m not too comfortable with either.

I have read many of the passionate, strongly worded opinion pieces from those demanding the statue come down and I agree with them, to a point. It’s clear that this is about the larger issue of transformation at our tertiary institutions, evinced by how the protests have spread to other universities.

Many progressive academics and activists are excited about how these protests have come from the ground up and signal a conscious awakening in many students. It is exciting to see this sort of activism. I also agree with the need to transform our universities – especially UCT.

But I struggle to see how taking the statue down will represent anything but the smallest of symbols in that larger fight. Will it signal any really institutional change?

And of course, this question is mocked by those demanding its removal, but it’s a real concern: when do we stop? Every historical figure can be contested. We could argue to take down South African statues of Mahatma Gandhi, who wasn’t exactly the best friend to this country’s black majority. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, in 10 or 20 years, in a more radical time, those voices calling Nelson Mandela a sell-out swell into a majority and demand the removal of the many public symbols and statues in honour of our first democratic president.

Instead of merely keeping or removing the statue, there is a far more nuanced and powerful way to deal with this statue, as we have with other symbols of our past. We re-work it. Keeping this amazing spirit of public activism, we get input from the ground up of how to alter, how we remember this history and adequately reflect how it is now perceived. This is what public art can do. (And let’s face it, Cape Town desperately needs some genuine public art after its recent series of commercialised blunders). Several commentators have already made this point but it just doesn’t seem to be gaining enough traction and I don’t understand why.

Business Day columnist Chris Thurman made some excellent points in his article over a week ago.

“Instead of approaching the statue as a static monument with a fixed meaning that must either be endorsed or condemned, why not commission an artist or group of artists to propose a creative response? The statue of Rhodes could be modified, or incorporated into a larger work, making it part of a continuing dialogue rather than a monumental monologue,” writes Thurman.

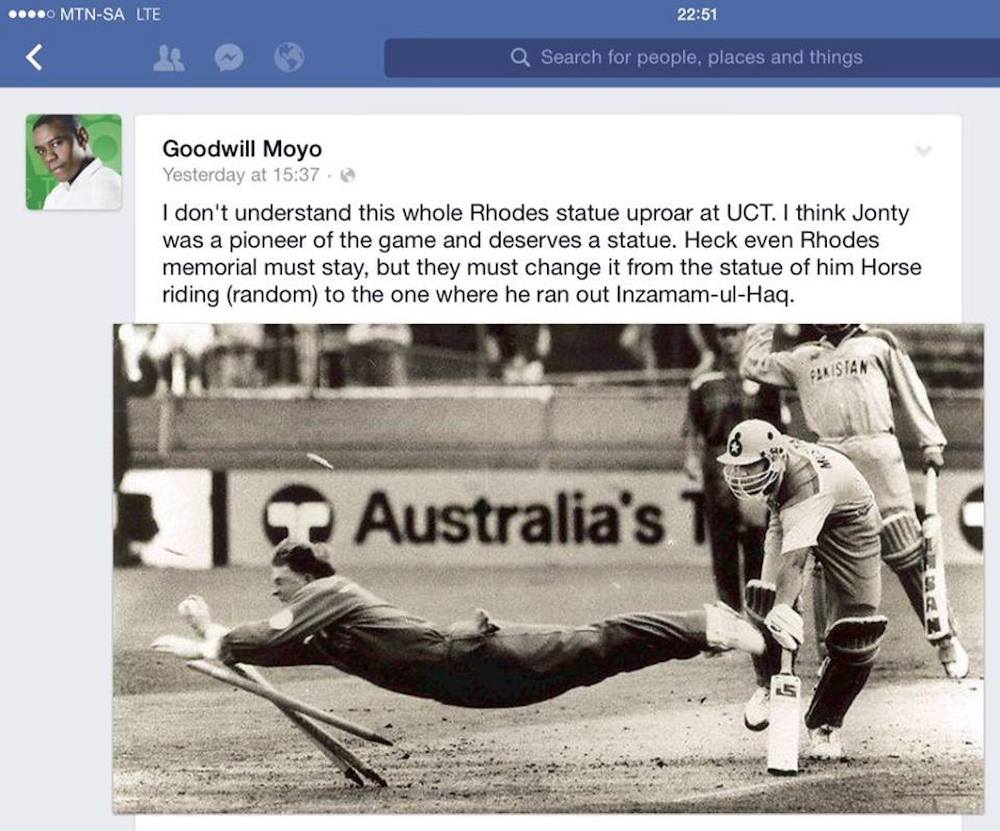

Thurman’s subsequent cheeky tip for modifying Rhodes Memorial on Devil’s Peak, Cape Town, another site honouring Rhodes, reminded me of a hilarious tongue-in-cheek response to the debate by one person on Facebook. The post went viral and illustrated how we can lighten the heavy burden of history and make it our own.

Albie Sachs took up the baton, with an excellent piece offering a historical view of how this sort of thing has been done in the past.

Sachs describes two “historically offensive” murals in South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, London, that showed Jan van Riebeeck hoisting the Dutch East Indies flag and another a bucolic wine farm.

“The majority of South Africans were either rendered invisible or, at best, portrayed as smiling natives. Slavery, dispossession and disenfranchisement were simply not there,” wrote Sachs. Together with some culturally sensitive high commissioners and artist Willem Boshoff, the work was redeemed and reworked.

The murals were covered with transparent glass panels “that recorded the names of the indigenous people and slaves whose voices had been silenced in the past. The result is striking. The viewer is compelled to look at and interpret the murals with present-day eyes and sensibility. A visually arresting and historically powerful new work of art emerged, based on seeking transformation rather than obliteration.”

It’s an obvious point and the same was done with Constitution Hill in Hillbrow, which was built on the remains of the old fort prison, and the placement of Freedom Park alongside the Voortrekker monument. Anton Harber, writing about the latter, points out that “Rather than throw out the history, it has been made part of a bigger story. When one is there one cannot but compare the forbidding, domineering, fascist architecture of one monument with the gentle, welcoming design of the other, and the exclusionary way in which one story is told alongside the inclusive nature of the other.”

So why, despite all these excellent arguments, has the debate become so polarised? As activist and artist Germaine de Larch asks in her blog: “What is this reductionist need to destroy, remove, erase? It undermines the power of reappropriation, redefinition and, frankly, creativity that is the right and responsibility of any and every human being living in a complexly historied space – which is ALL spaces.”

Because tearing down the statue, I can’t help but feel, is a dumbed-down answer to a complex problem.