“They accidentally shoot more niggas out here than any place in the world,” the comedian Richard Pryor said in the 1970s about police brutality in the United States. “Every time you pick up the paper: ‘Nigga accidentally shot in the ass.’ How do you accidentally shoot a nigga six times in the chest?”

With comments like these, Pryor – arguably one of the most radical comedians of our time – roused many with his critique on the plague of racism and racial profiling.

And 40 years after Pryor spoke those words, Los Angeles native Kendrick Lamar broached the same topic. But unlike Pryor, Lamar received a vitriolic response from the black community.

“How dare you open ur face to a white publication and tell them that we don’t respect ourselves … Speak for your fucking self.” Rapper Azealia Banks tweeted after rapper Lamar’s January interview with Billboard magazine went viral.

Rap artist Kid Cudi’s sentiments went like this: “Dear black artists, dont talk down on the black community like you are Gods gift to niggaz everywhere.”

When asked about the spate of killings of African-Americans at the hands of the US police, Lamar told the publication: “What happened to [Michael Brown] should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don’t have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us? It starts from within. Don’t start with just a rally, don’t start from looting – it starts from within.”

Following an almost full year of international protests in 2014 and this year against a system that led to the deaths of African-Americans such as Trayvon Martin, Brown and Eric Garner, to turn and point a finger at black people without digging up the causes of violence and the politics governing the black body seemed to be a let down.

This was especially true for Lamar, whose previous songs – such as Sing about Me, I’m Dying of Thirst from his 2013 album Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City – touch on issues such as drug abuse and gang violence that pervade the projects, as his lyrics articulate: Dope on the corner, look at the coroner/ Daughter is dead, mother is mournin’ her/ Strayed bullets, AK bullets/ Resuscitation was waiting patiently but they couldn’t bring her back.

The culpability of black people

A month after the Billboard interview, he released The Blacker the Berry – the second single from his album To Pimp a Butterfly, which came out in February. On the song, Lamar’s lyrics at first metaphorically trace violence against black people, from the Atlantic slave trade to the high prison incarceration rates that affect them. But later in the song, as he does in the interview, he places the burden back on the shoulders of black people.

So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street? / When gang banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me? his lyrics ask.

Lamar knows that his opinion on the culpability of black people in their oppression is conflictual.

In fact, throughout the song he reminds us that he is “the biggest hypocrite of 2015”. And it is this swirl of lyrics containing self-conflict, self-doubt, self-hate and self-love that sets off Lamar’s third studio album from its predecessors.

With his signature verité-style rap in To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar employs rhymes the way the late Pryor used his jokes to tell about the complexities of being a black man in a society where their options are limited.

I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it /Institutionalised, I keep runnin’ back for a visit, Lamar raps on Institutionalized – a song so honest and open that it evokes the laments from cash-strapped, broken-hearted blues singers: If I was the president/ I’d pay my mama’s rent/ Free my homies and them/ Bulletproof my Chevy doors/ Lay in the White House and get high, Lord/ Who ever thought?/ Master take the chains off me!

Institutionalized, which features singers Anna Wise, Bilal and rapper Snoop Dogg, plays out on a winding backdrop of synthed-out, psychedelic beats – a sound that is ubiquitous on the album.

A place of no hope

Evoking G-funk (or gangster-funk) with beats that hark back to the early 1990s, when West Coast rappers such as Eazy E or Too $hort waxed lyrical about chilling out or gang banging, Institutionalized comes from a place of no hope.

It’s a place, or rather a country, where a 2013 study titled Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System by the Sentencing Project, a group based in Washington, DC, reveals that “one of every three black American males born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime”.

Throughout To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar doesn’t shy away from the effects of institutional racism that manifest in such statistics. In a digitally manipulated interview with the murdered rapper Tupac Shakur, which forms part of an outro on the album, the activist and musician, who was gunned down in 1996, says of being black in the US: It’s like they take the heart and soul out of a man/ out of a black man in this country/ And you don’t wanna fight no more.

Meanwhile, quoting Sofia – a resilient character who faces domestic abuse and severe racism in Alice Walker’s classic 1982 novel, The Color Purple – Lamar’s lyrics in the song Alright claim: All my life I had to fight.

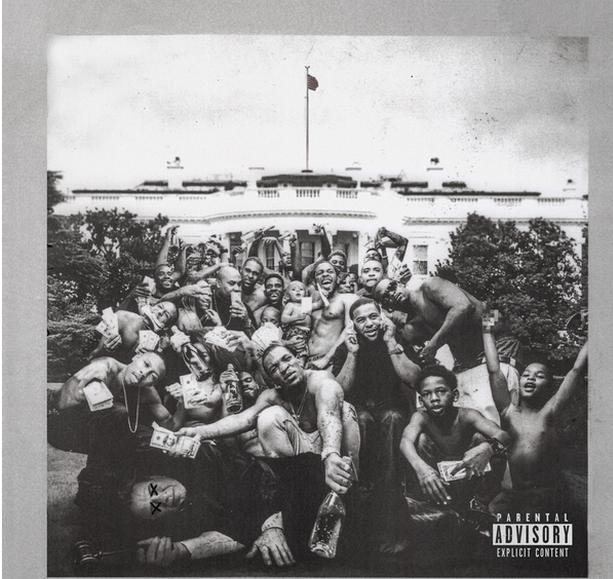

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly album cover

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly album cover

But in Lamar’s raw and conflictual style, Alright’s lyrics show us the light, even if it’s low: We been hurt, been down before/ Nigga, when our pride was low/ Lookin’ at the world like, ‘Where do we go?’/ Nigga, and we hate po-po/ Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure/ Nigga, I’m at the preacher’s door/ My knees gettin’ weak and my gun might blow/ But we gon’ be alright.

And as the saxophone shouts on the song’s horizon, the words “we gon’ be alright” are reassuring and get repeated by the song’s producer Pharrell Williams.

There’s no holding back

Lamar echoes this voice of hope in the album’s closing song, Mortal Man, in which he tells Shakur: In my opinion/ only hope that we kinda have left is music and vibrations/lotta people don’t understand how important it is. Sometimes I be like/ get behind a mic and I don’t know what type of energy I’mma push out/ or where it comes from.

So on his latest album, with the power of his gritty raps that transform him into multiple characters, Lamar talks politics, alcoholism, gang activity and love, without holding back.

And he does this with the music industry’s best. From producers such as Flying Lotus, Sounwave and Pharrell to musicians such as Thundercat and George Clinton from the funk band Parliament-Funkadelic, each of these musicians winds down Lamar’s lyrical path that eventually spins into a cocoon of free jazz, (G-)funk and psychedelia.

And similar to Pryor’s stand-up performances that delved into his life growing up in a brothel or having multiple sclerosis, which eventually killed him 10 years ago, listening to To Pimp a Butterfly is not easy and will leave you sad, mad or even in love.

Either way, the album will be spoken about for a long time, much like the legacy of funny man Pryor.