China's President Xi Jinping with President Jacob Zuma ahead of the fifth Brics summit.

With China’s flagship event showcasing how its influence has grown in Africa set for the continent this year, the focus will inevitably be on the amount of new aid and loans Beijing dangles at the continent.

The last summit of the triennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac) saw President Hu Jintao put on the table $20-billion in loans to African countries, doubling its previous offer.

As bilateral trade volumes have grown, Beijing will be expected to offer billions more at this year’s forum in South Africa, despite its domestic economy having cooled in recent months.

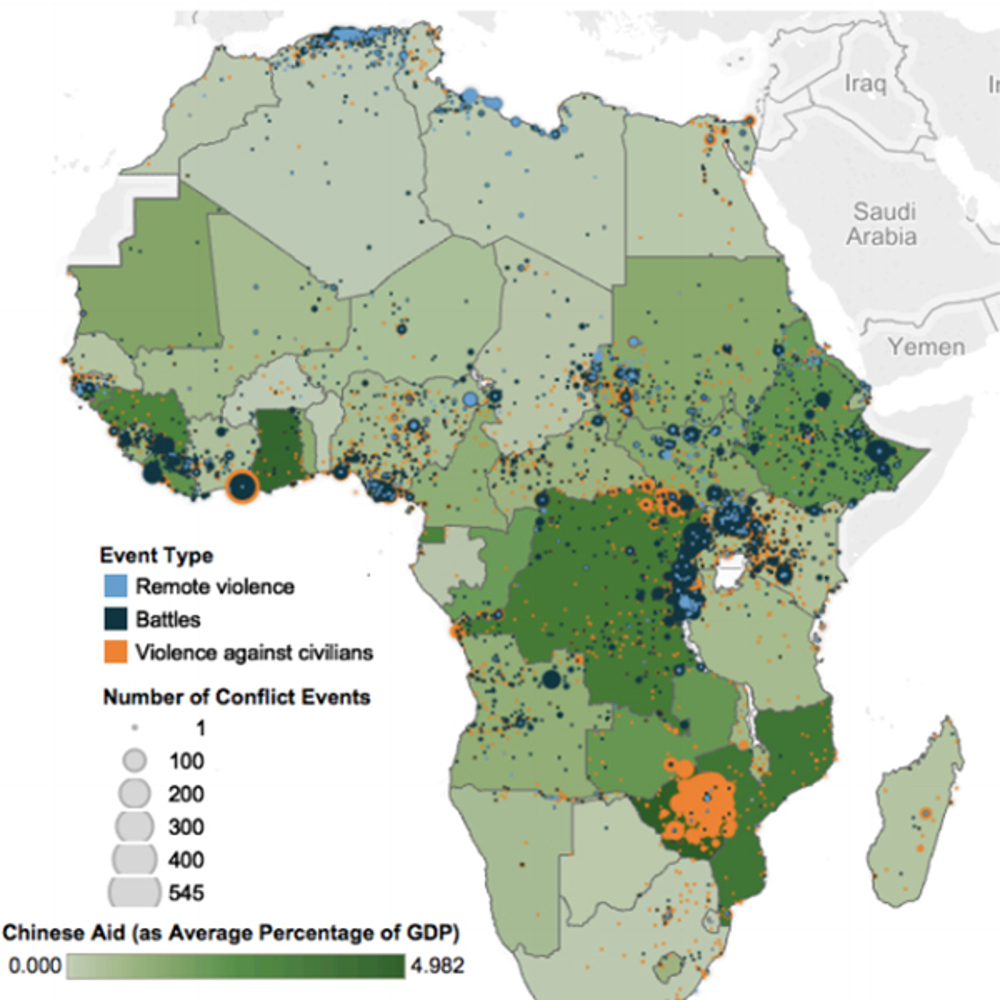

However, Africa can also expect to witness notably more incidences of state-sponsored domestic violence, both against civilians and competitors such as rebel groups, as Chinese aid increases, a new study shows.

Authors Roudabeh Kishi and Clionadh Raleigh, of the University of Sussex’s Department of Geography, say this effect is largely because aid from China is fungible, with its use determined by recipient countries.

Their working paper, titled “Chinese Aid and Africa’s Pariah States”, finds that political violence by the state increases with receipt of Chinese aid.

The same is not observed with aid from ‘traditional’ or Western donors, which comes tagged with conditions.

When money breeds bad ways

Because Chinese aid is disbursed under a “non-interference policy” that does not seek to influence the domestic policies of recipient states, leaders have a lot of leeway over where it is used.

“Due to the lack of obvious conditionality, African leaders can use Chinese aid in the ways they see fit and suited to their political, economic and social needs. In practice, Chinese aid directly supports the regimes of states,” the authors write.

The same effect would be observed with any other country offering unconditional aid, the researchers told Mail and Guardian Africa.

“Similarly, if the Chinese model was to mimic traditional aid flows in which aid packages were to become conditional (and could not be readily used for whatever outcome the state chooses), then we would assume that these aid flows would result in a similar outcome as other conditional aid flows.”

Critics of Beijing’s aid say that its packages provide funding for pariah states, while undoing the longer-term benefits from the conditions tied to the aid given by the West. China has also been accused of only seeking Africa’s natural resources, most notably by US president Barack Obama, and cultivating ties with states accused of poor human rights so as to rope in supporters for Beijing’s own iron-fist internal model.

Surprising finding

But the study, perhaps a bit surprisingly, finds that this is not the position. While Africa’s resources are important for feeding its growth, the world’s second biggest economy also seeks new markets for its goods, and to build international coalitions with non-Western states including those in Africa, for pursuits such as support for its “One China” policy.

As such, its aid is directed towards whichever countries satisfy those needs, with a recipient’s institutional quality or type having no bearing on its choices.

“Hence, acknowledged pariah status is not a pre-requisite for large Chinese aid packages,” says the study, noting that aid from Beijing flows to countries as diverse as South Africa, Ghana, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Sudan.

The only countries that have not benefited from China’s aid have been pro-Taipei Burkina Faso and Swaziland, and The Gambia until it recently cut ties with Taiwan.

Essentially, China is an “equal-opportunity” lender.

“Though China isn’t specifically giving aid to ‘pariah states’, it is making states into pariahs through providing resources to state leaders who are unafraid to use repression as a means to quell competition,” the researchers noted.

The fungibility of China’s aid is cited for the “significantly” higher rates of violence by states, both against competitors and against civilians.

This is evident when compared with aid from traditional donors, and even when the researchers mitigated for different rates of resource exports and the strength of the rule of law, and any other aspect of the state which may help explain existing violence rates.

“If the state has complete control over its budget, it will use its position to bolster its capacity to repress any potential opposition in order to secure its position,” the study noted.

Western aid is not absolved of blame — it also fuels conflicts by making the “prize” of rebellion more attractive to insurgents, who would very much like the power to redistribute it and support patronage networks.

The jury also remains out over the efficacy of “tied” aid — while its supporters claimed it had in the post-Cold War period made African countries better governed, scholars note there was little evidence of this.

Graph source: ACLED

The study notes that China has successfully exploited the angst around Western donor preconditions by leveraging on its policy of non-interference, shared colonial history and by dangling its recent turbo-charged growth at African leaders.

China shifts

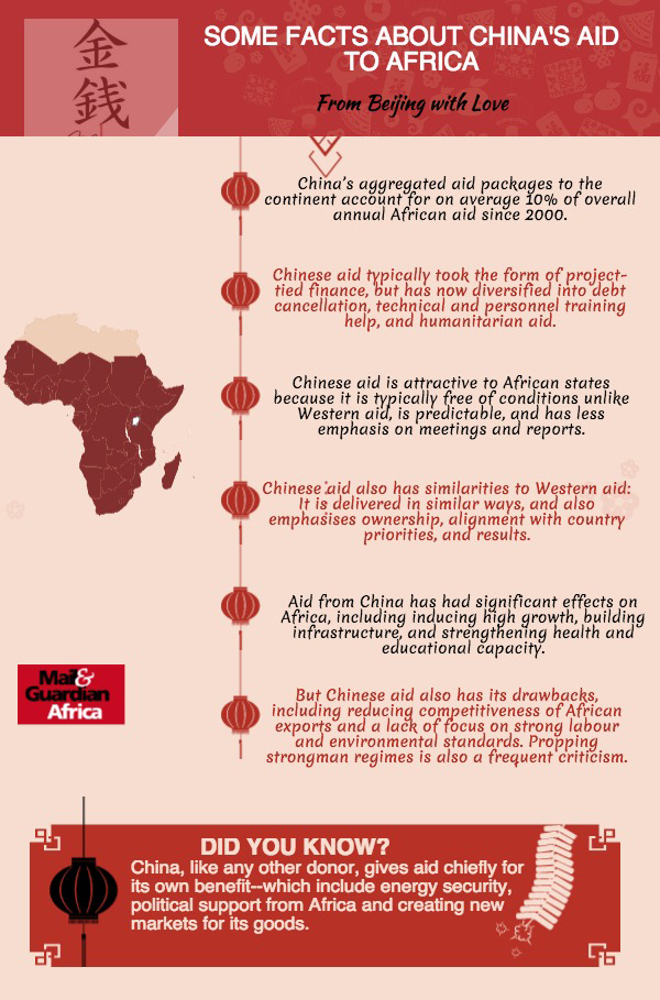

And as uptake of its “few-questions” aid took off, Beijing diversified from project-tied aid into debt cancellation, technical and personnel training help, and humanitarian aid, even if its aid flows remain significantly less than those of other international donors.

Chinese aid is however not as no-strings-attached as advertised, the paper highlighted. Its model poses the danger of countries remaining dependent on resources, while increased competition has also made African goods uncompetitive among other criticisms such as on labour and environmental standards.

To make their case, the researchers tested whether levels of armed violence rose with increases in Chinese aid, and whether it was specifically perpetrated by the state.

They also compared the incidence of violence under Western aid flows, and controlled for variables such as resource dependence, GDP strength, democracy or lack of, the rule of law, populations and existing conflict.

Some of their findings included that China does not specifically target countries with more natural resources, and that autocratic regimes do not generally receive a higher proportion of aid.

Because Chinese aid is meant to benefit China, they also found that countries with a weaker rule of law get more aid as they have an environment that allows Chinese business to flourish.

Additionally, increased Chinese aid relative to a state’s GDP led to more incidences of state-supported conflict, while rebel groups or other conflict actors were not seen to be taking up arms any more due to the availability of Chinese aid.

“In short, Chinese aid increases the ability go the state to repress domestic competition, opposition and civilians. Compared to traditional aid, the effect is limited to state forces and goals,” said the study.

This is true even if internal country dynamics are different, it noted, citing countries such as Ethiopia, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

“Often the strategies and tactics for ensuring regime stability and regime longevity might be outside the preferred conduct of Western aid donors, hence unconditional/Chinese aid is attractive. Other scholars have noted the use of Chinese aid for ‘prestige’ projects or funnelling money to allies and supporters for the same reasons,” the authors told M&G Africa.

But despite this, or perhaps because of it, Chinese aid has been particularly useful to African leaders seeking to remain in power.

And due to its win-win relationship, the Sino-African relationship will likely endure, suggesting traditional donors may have to think of better ways to make their aid model attractive once again. – Lee Mwiti

This article first appeared on the Mail & Guardian‘s sister site, mgafrica.com

Visit mgafrica.com for more insight on the African continent.