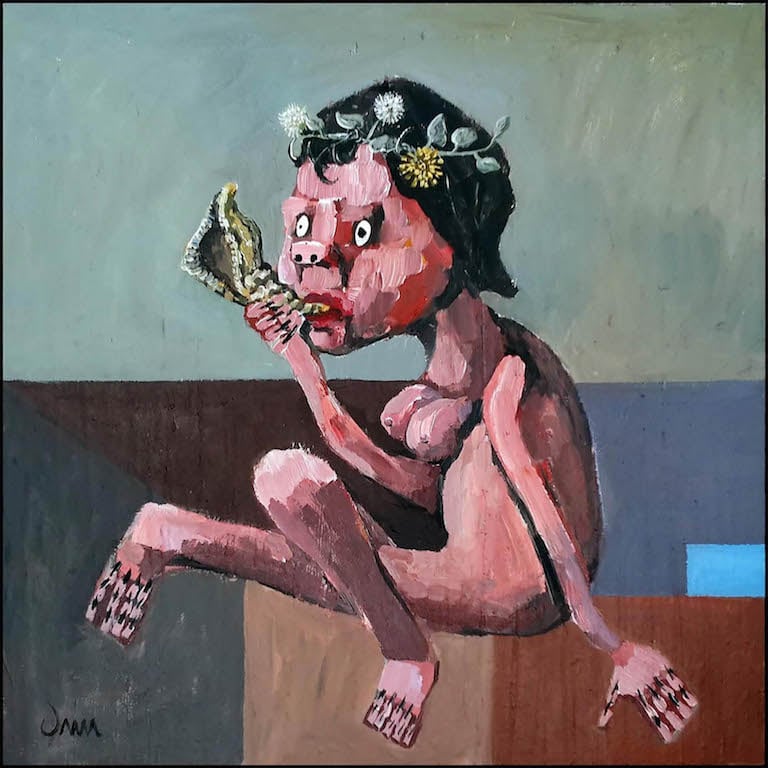

‘Untamed sense of control’: The vocal range and skill of Inge Beckmann is one the factors that has made Beast’s album 'Bardo' a huge success.

It takes exactly 36 seconds for Beast’s second studio album, Bardo, to announce itself as one of the most exciting South African releases in years. After some intricate riffing and urgent, declamatory vocals from front woman Inge Beckmann, the music suddenly falls away – the first beat of the next bar passes in silence – before the gates of hell blow open and the gut-clenching force of two fuzzed-out bass guitars is unleashed full throttle.

Two bass guitars?

Yes.

And Inge Beckmann?

Uh huh.

It’s an unusual set-up, and one that might not work if its vision wasn’t so consummate. Beast is an interstitial animal – a glorious metal, grunge and biker rock gumbo – and one that trades in contrasts and contradictions. Indeed, the next time we’re treated to the ridiculously heavy chorus of opening track Healer, Beckmann’s vocals soar above the fathomless bass attack, demanding “Are you witch, or are you a healer?” It’s a brilliant, wild and satisfying moment – a beautifully recorded testament to what, some say, is this country’s finest live rock act.

Beast was formed as an experiment of Taxi Violence’s Rian Zietsman and Louis Nel. The two bought themselves bass guitars and began a side project in the basement of the house they were sharing – driven, as Zietsman puts it, by the incredulity that “no one had tried [the two-bass set-up] before”. The duo’s suboctave sound found its natural complement in Beckmann’s piercing vocal style and she was also instrumental in providing a “recipe” for Beast’s early songwriting exploits. Werner von Waltsleben, a sensitive and powerful drummer who has been with the band for two years, completes Bardo’s musical line-up.

The album is a sumptuously produced and faithful rendering of the band’s immense stage power – an achievement underscored by the fact that Zietsman mixed the tracks himself. He revelled in this “double responsibility that I owed to both the band and the record” – and Bardo certainly continues the trend of improving production standards in South African rock albums. Von Waltsleben’s drumming is crisp and rich throughout, the bass is concussive on every track and Beckmann’s vocals have the searing clarity of midday sun.

Lyrically, much of Bardo – the title refers to a state in Tibetan Buddhism between death and rebirth – concerns itself with the neither-nor. In Vesica Piscis – the name of a shape consisting of intersecting circles – the speaker claims to be “the sum of two parts”, an unholy thing whose “knees [bend] the other way” during prayer.

In this track, as if to prove the point, Zietsman also plays a full-on blues rock guitar solo voiced on the bass.

Elsewhere, whether waxing depressive (Out Here), or – as on Wrong Side – defiant (“I’m on the wrong side of the road/ But the right side of life”), this fixation on paradox pushes the songs decisively into the dark, primordial musical territory already established by the rhythm section.

Beckmann is conscious of this trend in her writing, describing the process as “taking two things that don’t make sense and sewing them together”. Neither is she innocent of the effect that this interpretive burden has on the listener: “I like that people have to read their own meaning into the words,” she says.

At their very best, though – Healer, Black Hole, Alliance – Beast achieves what only the most ambitious rock bands even dare to try: a totality of vision and execution, a marriage of form and content. On these tracks, all the angst, confusion, anger – the Sturm und Drang of the album – find their perfect musical expression.

Black Hole is the most ambitious, and probably also the best track on Bardo, and sees Beckmann indulging in what she jokingly refers to as “method singing”. A ferocious, contrapuntal bass exchange reminiscent of Rage Against the Machine opens the track, before it abruptly spins out into an ethereal meditation on our place in the cosmos – Beckmann in full “androgynous choirboy” mode here, “Beholden to the sun … drawn into the light”.

Then an unhinged build-up flirts with dissonance before whirling teeth first into a desperate, delay-drenched chorus of “Got to get out, got to get out, got to get out of your black hole” – the basses thundering and the drums swinging in triplets like Buddy Rich on bad drugs. It’s another moment of tremendous musical accomplishment and the kind of thing any fan of songwriting should relish.

Of course, though – and it’s a point that does not detract from the manful contributions of Nel, Zietsman and Von Waltsleben – the mother of the dark child and the high priestess of the order, is Beckmann. What Bardo has delivered – to my ears, more so than anything she recorded with Lark – is a supreme showcase for one of the most special voices this country has ever produced.

Straight-backed and imperious in front of the microphone, Beckmann is an incendiary live performer – her voice given free reign to burn through the crowd in the higher-mid frequencies. Yet – and it is the band’s most sublime contradiction – she marries this feral vocal presence with what Bob Dylan (talking about Roscoe Holcomb) once called “an untamed sense of control”, precisely marshalling her voice through an astounding array of tones. On Bardo, Beckmann weeps and roars and keens and davens and growls and moans the way ahead – expertly giving voice to the themes and psychic preoccupations of the songs.

Bardo might not be a flawless album – Are We Alive? smacks of filler to me, Down does not do full justice as a closer, and I’m not convinced by the backing harmonies on Chant – but it is certainly a huge success and a staggeringly bold artistic statement from Beast.

Everyone’s read enough about how for many years, South African rock bands have taken their cue from American and (to a lesser extent) British and Australian models – and that acts that have gained success over here are, simply, more or less successful facsimiles of foreign bands who’ve got CDs you can buy in Musica.

Bardo equates to a brazen casting-off of that inferiority complex, a wrecking ball to break new ground for other local rock acts to follow. There is no one out there who is doing what Beast does – and certainly not quite so well (believe me, British drum and bass duo Royal Blood become redundant the second you’ve heard Beast).

With online platforms such as iTunes providing international exposure previously unavailable to most local artists, Beast hope that Bardo might lead to “other projects”, potentially tying in with the film and television industries.

Admirably, they have set their stall out to be “working artists, and not just a touring band”.

Bardo’s industrial, pneumatic sound and morbid subject matter might not be everyone’s default but there is enough palpable quality on display here to earn the album crossover appeal. Beast has been gestating and sure, Bardo is a dark birth – under a constellation of bad signs – but it’s one the South African music scene should nevertheless welcome with pride and gratitude.