Cellphone operators are increasingly offering not only cross-border transaction services but are also interconnecting their services.

Moving money across African borders with the click of a cellphone button just keeps getting easier. The mobile money revolution – essentially the use of cellphones to access financial services – is already transforming the face of financial inclusion on the continent.

But growing cross-border options and the interconnection of mobile operators is hastening this change, which has implications for traditional financial services such as banks and money transfer operations, according to experts.

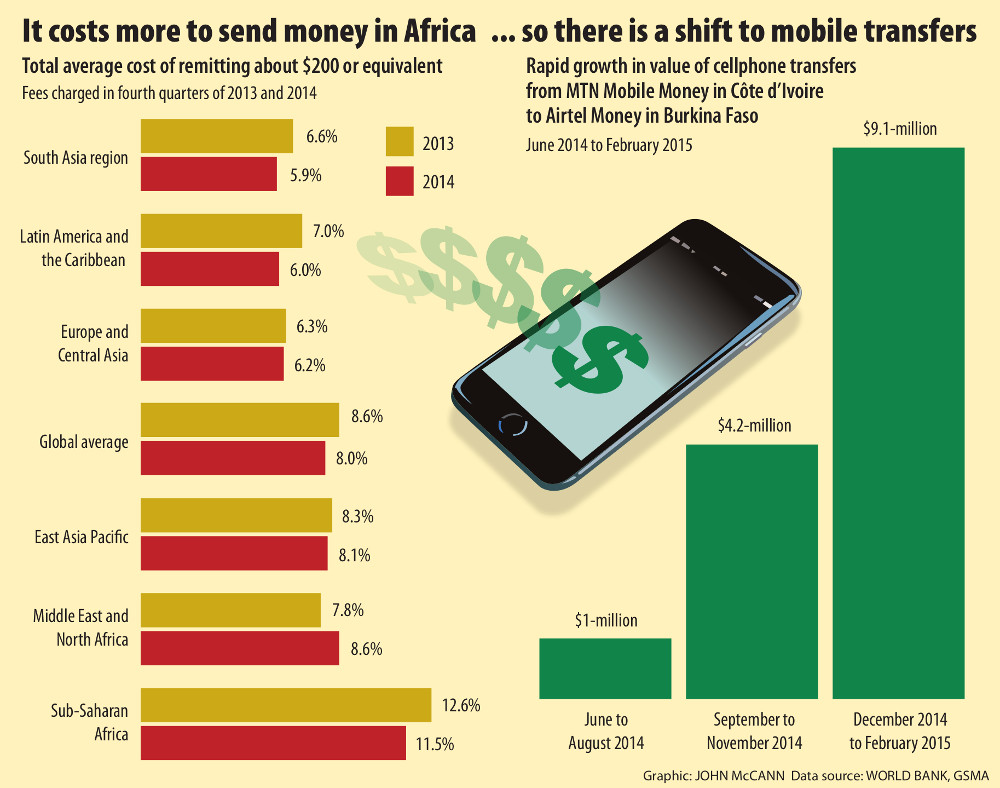

For a start, it is driving down the costs of international remittances in sub-Saharan Africa, where they outstrip the global average – although remittances from South Africa to neighbouring countries are the most expensive in the region, according to the World Bank.

With well-established money flows flying from cellphone to cellphone, most famously through services such as M-Pesa in Kenya, cellphone operators are increasingly offering not only cross-border transaction services but are also interconnecting their services.

Interoperability (the ability of customers of different mobile services to transact with others) has already been a success for MTN in West Africa. And, early this month, it was announced that, in East Africa, the epicentre of the mobile money revolution, MTN Mobile Money will be connecting with M-Pesa, the mobile money transfer service launched by Safaricom, in which Vodafone has a 40% stake.

Although this is not the first cross-border interconnection in the region, it links the two largest operators in countries with about 90-million mobile customers, according to the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (GSMA), an organisation of mobile phone operators.

Money corridor

The agreement will link M-Pesa customers in Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique and Kenya, and MTN Mobile Money users in Uganda, Rwanda and Zambia.

The first corridor between M-Pesa in Kenya and MTN in Rwanda is expected to be up and running by the end of May, MTN’s group head of mobile financial services, Serigne Dioum, said this week.

Other corridors would follow soon after, pending the finalisation of technical integration and approval from the countries’ central banks, he said.

Partnerships such as these will prove stiff competition for traditional money-transfer services such as Western Union, given the accessibility of cellphones and the relative affordability of the products on offer.

“Our ambition is to move money transfers from traditional channels to MTN Mobile Money channels,” Dioum said.

In a bid to achieve this, he said, it had priced its transfer offerings aggressively at 5% of the transaction, compared with the 10% to 15% offered by other service providers.

Although this would not happen overnight, given the extensive cellphone penetration and the good traction of mobile options, MTN expected that it would be able to capture at least half the market very quickly, Dioum said.

Global remittances

According to the World Bank, global remittances to developing countries amounted to $436-billion in 2014, with remittance flows to sub-Saharan Africa reaching $32.9-billion. But the value of international remittances by cellphone is still small, making up just 2% of the total in 2013, according to the bank.

“International interoperability of mobile systems and anti-money-laundering and the countering of financing terror regulations still create barriers to the entry of new players,” the bank said in its most recent brief on migration and remittances. It called for the regulatory framework to be simplified to foster competition.

The cost of remittances in the sub-Saharan region average about 12%, above the global average of about 8%.

The potential of cross-border interoperability is highlighted in a report by GSMA, which examined the interconnection between MTN Mobile Money in Côte d’Ivoire and Airtel in Burkina Faso. After launching their cross-border partnership in 2014, remittance flows from Côte d’Ivoire to Burkina Faso through the mobile operators leapt from $1-million for the months of June to August to $4.2-million for September to November, and reached $9-million for December 2014 to February 2015.

According to the technology firm MSF Africa, the remittance flows among the countries covered by MTN and Vodafone in Africa are estimated at about $3.6-billion a year. Rachel Balsham, the deputy chief executive of MFS Africa, said the interconnection between the companies represented a tremendous opportunity for intra-African remittances.

The firm serves as a switch between mobile money accounts of different providers, similar to the role Saswitch plays between different banks in South Africa, and will connect MTN Mobile Money and M-Pesa in East Africa.

Cross-border trade

Balsham, citing World Bank data, said remittance flows between Uganda and Kenya averaged about $530-million a year. Connecting the two operators would boost not only remittances but also cross-border trade, which was particularly strong in the region, she said.

Given that bank account penetration in most African countries was below 20% and mobile penetration was very high, mobile wallets were a key driver of financial access, notably for the unbanked, Balsham said.

Prices among traditional money transfer operators varied according to the corridor, but could be lower in very competitive corridors such as Uganda-Kenya, which averaged about 9%, she said. But in some cases traditional ways for remittances were already less expensive and the mobile-to-mobile channel might not be the cheapest, she said. In addition, other factors such as control and liquidity of the local currency came into play in the total cost of remittance.

But Balsham said, there were several unique attributes that made mobile-based transactions more attractive, including the fact that mobile channels were available around the clock and instantaneous.

There was also a major security advantage, she said. Instead of leaving a money transfer office with a large sum of cash, recipients could withdraw any amount at an MTN Mobile Money or M-Pesa agency, which were widely distributed around the country.

This was in stark contrast to banks, which were few and far between, and had a limited number of branch offices.

Two roles

But, Dioum said, banks played two roles in facilitating mobile money transactions. The first was in respect of banking regulations. In the case of MTN Uganda, it did not have a banking licence and so had partnered with Stanbic Bank to get the necessary approvals. Second, for international money transfers, the management of the currencies was done in conjunction with banking partners.

But the rapid changes being seen in mobile money raises the question: What does this mean for banking institutions in the long term?

According to the chief executive of the FinMark Trust, Prega Ramsamy, banks must either “face the competition by cutting down costs and be more flexible in their approach, or they will lose it to the less expensive money providers through the telecoms”.

This was particularly relevant in countries with a lack of basic technologies and infrastructure, he said. He referred to Kenya, where about 80% of the population lived without basic necessities, but had cellphones.

Arguably, South Africa should provide fertile ground for mobile money operations but it has not seen the same level of adoption as other countries.

According to the World Bank, the cost of sending money from South Africa to Zambia, Malawi, Botswana and Mozambique remains the highest in sub-Saharan Africa.

Banking infrastructure

Ramsamy said the banking infrastructure in South Africa was sophisticated and banks were already providing services through cellphones, such as making payments, and ATMs and branches were readily accessible.

According to Finmark’s 2013 FinScope survey, which measures financial inclusion, it takes less than 20 minutes for an individual to access an ATM. But mobile money had two chief advantages, namely distribution and low cost, Ramsamy said, which were difficult for banks to replicate at the levels seen in places such as East Africa.

Extensive agent networks also came into play, he said, with Safaricom, for instance, boasting 81 000 agent outlets in Kenya.

The regulatory environment is another factor.

“The regulation in East Africa is not as stringent as that of South Africa, which prevents the replication of the East African system in South Africa, due to the strict regulations in banking and mobile banking,” Ramsamy said.

Network competition

Gyongyi King, the chief investment officer of CaveoFund Solutions, an investment management company, said the greater competition between mobile networks in South Africa was another element.

Developing an appropriate cost mechanism was much simpler in countries such as Kenya where Safaricom was the dominant player.

King said the relationship between the banks and telecoms companies had so far been a partnership, but the jury was out over what it may mean for banks in the long term. But, without an all-important banking licence, there was still much that cellphone operators could not do, she said.

Nevertheless, the growth of mobile money was a game changer and was increasingly bringing the informal sector into the formal banking net.

A recent joint venture between Safaricom and KCB, the largest bank in Kenya, was an example, she said. Using the records of an M-Pesa customer’s balances and transaction history, the bank was able to obtain a credit score and then extend micro loans to the consumer, King said.

Western Union did not respond to a request for comment.