There is widespread agreement that South Africa needs to embark on a programme of industrialisation, but the point of contention is how it should take place.

In March President Jacob Zuma announced that South Africa will create 100 black industrialists in the next three years. At the inaugural Black Industrialists Indaba at the Gallagher Convention Centre in Midrand, he said he wanted to see “more factories and other means of production being owned by black people so that South Africa could achieve economic transformation”.

To support the initiative, known as the Black Industrialists Development Programme, the deputy trade and industry minister, Mzwandile Masina, said his department had set aside an initial R1-billion to recapitalise the National Empowerment Fund.

In an interview with the Mail & Guardian, Masina said there was an ongoing debate about how much money the programme required. He said the R1-billion was to “kick-start” it, but that it would need “huge sums of money” that could come from the Public Investment Corporation, the Industrial Development Corporation, the Development Bank of South Africa and other government development finance institutions.

“The Land Bank, [the development bank], the Brics [Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa] bank … everybody. That’s the combination of the sources of funding. This is what is called syndicated financing – the money doesn’t have to come from one point. We should be able to say that there is X billion rands for this programme; those who need money and especially incentives should come apply,” said Masina.

Policy framework

To ensure the success of black industrialists, Masina said the department of trade and industry had come up with a policy framework that would be presented to the Cabinet in June.

The policy outlines aspects such as access to cheaper loans and grants and tax rebate incentives to open factories in industrial development zones, and proposes steps to target procurement and create a dedicated export market.

He said, if adopted, the policy, coupled with the undertaking by the treasury to spend R4?trillion in the medium term (three to five years), would ensure there was an appetite to buy what the industrialists produce.

“There is a market – the state – and we are going to use it to buy goods and services [produced by the black industrialists]. We are also opening opportunities on the continent. [The department is] opening what is called a tripartite free trade area so that there are new markets that we create for our own black industrialists,” said Masina.

The tripartite free trade area is a combination of three regional blocs: the Southern African Development Community, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa and the East African Community.

Welcome news

For Ntau Letebele, the chief executive of black-controlled Lerechabetse Advanced Products, an entity that manufactures high-pressure and high-temperature valves, the funding put aside by the government to assist black industrialists is welcome news.

Letebele said his business needed government support and funding to build its capacity. He said his company manufactured rock-drill bits for mines and hoped to consolidate its position in the manufacturing sector, which is currently dominated by two multinationals.

“We want the mines to procure from us. Our facility is geared up 24 hours a day. We have the machinery, the requisite personnel and we are producing a comparable product,” said Letebele.

He said the government’s decision to fund black industrialists was a step in the right direction because one of the challenges his black-owned company has faced is accessing funds from commercial banks. Letebele said, however, that funding alone was not enough.

“We also need support to access markets. [The government] must put pressure on the mines and place a special condition that a certain percentage of their procurement should be from black-owned companies.”

Government protection

Letebele said black industrialists also need the government to protect South Africa’s economic sectors because they cannot flourish when the playing field is not level.

“How do you expect a factory in a township to compete with a multinational subsidised by its own government? Also, the people in charge of procurement at these foreign-owned mining houses don’t want to do business with us. There is no policy in place to help us supply these big mines,” he said.

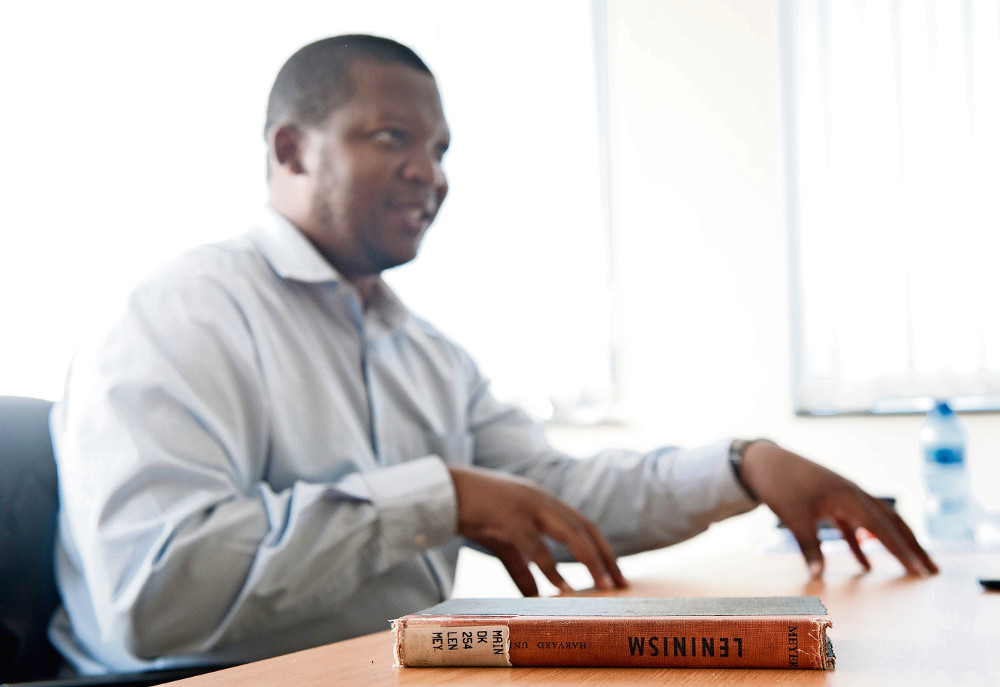

Associate professor Chris Malikane says the state cannot intervene in the mining sector because it does not own the mines. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

The M&G put these concerns to Masina, who said it was not for the state to say “‘you shall buy from this one and not that one’, because it then becomes uncompetitive”. He said black industrialists needed to pursue procurement opportunities with mining houses separate from the government.

Once state intervention was reduced to the level where the state could tell the mines what to do and not to do would amount to a bad business practice, according to Masina.

“You can’t do that. But once you regulate [the mining sector], which is why they get a licence, you can set up conditions. But the conditions should not be about the interests of [black industrialists] but the interests of the [South African] people,” said Masina.

State intervention

Christopher Malikane, a University of Witwatersrand associate professor in economics and a member of that National Planning Committee, said the state could not intervene in the mining sector because it did not own the mines.

He said the British and Americans owned the mines, and now Europeans were entering the market. South Africa was still a colonial state and could not industrialise because no colony had ever been able to successfully do so, according to Malikane.

“At the heart of it, the economics of it, an industrialist needs inputs in order to manufacture. Those inputs are raw minerals from the natural resources available in your country. But if the supply of those raw minerals and critical inputs is regulated by foreign companies who manufacture the same product that you want to manufacture, then you cannot have an industrialist agenda,” said Malikane.

In 2012 the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) conducted a study on beneficiation. The study revealed that South Africa is estimated to hold 80% of global manganese reserves, which have been identified as critical raw materials for Europe. The Numsa report showed that multinationals dominate in the South African mineral resources sector.

“That’s why for me, this talk of creating black industrialists is a wish: ‘Oh, we wish we can have that, these black industrialists. Imagine black people manufacturing … just imagine.’ It is a wish that is not going to take place,” said Malikane.

Government ownership

He said that before any government could create industrialists, it must first own its land and strategic sectors. Black industrialists would also need access to finance and to markets, but Malikane argued that government should not use its budget to fund the black industrialist programme as this was not sustainable in the long term.

He said the department of trade and industry’s policy on black industrialists, which would depend on development finance institutions for primary funding, was a problem because most of these institutions were funded by government departments, which in turn receive their money from the treasury.

“As you are aware, our country might be downgraded to junk status because our budget is incapable of meeting the current huge backlog. How will the treasury now fund these [development finance institutions]?” said Malikane.

But industrialist Herman Mashaba disagrees with both the department and Malikane. According to Mashaba, “industrialists cannot be created; they are born” and the nationalisation of strategic assets can only breed corruption, not industrialisation.

“An industrialist is someone who runs the whole value chain and is in control of the whole process – from manufacturing to final product. If there is no value chain, then you will have no chance,” said Mashaba.

100 black industrialists

He also questioned the thinking behind the 100 black industrialists that the government wants to create. He said the black industrialists programme, like black economic empowerment and tenders, would simply create a black elite who would only be given funding because of their political connections.

Masina said the department was not necessarily looking to “create” black industrialists, but wanted to upscale those already in existence. He said the department had received funding applications from 40 black industrialists, but would only look at these should the Cabinet approve the policy framework in June.

Malikane said the narrative in South Africa had shifted towards corruption: “The reason we are not growing is because these politicians are corrupt; they can’t manage the state, they can’t do this and that,” he said in response to Mashaba’s claims of state corruption.

Malikane said that even if the state was not corrupt, the industrial programme would still not succeed given the current economic dispensation where strategic sectors in the economy were owned by foreign multinationals.