Mmusi Maimane said the DA would take the water to another community that needed it.

It’s sad that 21 years into our democracy, the victory of a black South African to serve as leader is still celebrated.

Should we swallow this “giant” step for South African history wholeheartedly and without question? It seems as if many supporters are doing just that.

I don’t know … perhaps it’s because the fuzzy haze created by the rainbow cloth that’s been stitched on to our eyes still has to wear off.

Some are so drugged by it, enjoying the high that’s perpetuated by one acceptable black leader after the other that they’ve forgotten to think critically about what they’re consuming.

This is history? An opposition party (who racially represents a minority), finally has a black leader? What a milestone. I guess we will take what we can get – small mercies and all that.

Or not.

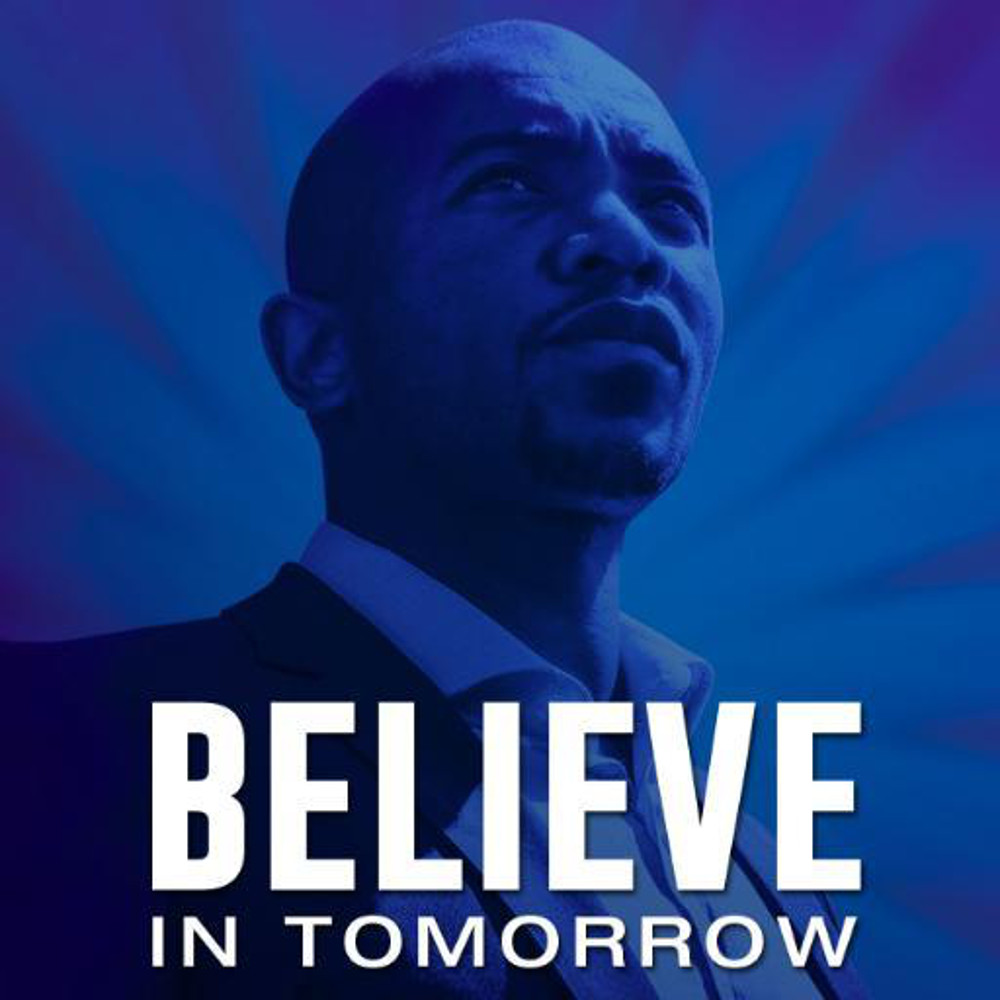

Mmusi Maimane has a few draw cards up his sleeve. He is appealing. He looks the part. He walks the walk. He’s relatable. He’s not a rough diamond that predominantly white Democratic Alliance followers have been asked to swallow.

Strategically, the DA made a good choice, clever on their part.

It begs saying that had any other black candidate been voted in as their new leader (not that they had much to go on), this unprecedented historical moment may have been discoloured … so to speak.

Maimane is literally the DA’s token – a tangible representation of a fact.

That fact? The DA needed a representative that reflected the majority demographic of South Africa, so that they could get that demographic to vote for them.

But does he really represent them, or does he just represent a black face in a sea of white that’s eager to say things like, “See, we know him”, or “We’re not racists, we love Mmusi”, or anything that any white liberal might say to assert their place in the current political environment.

(Obviously, they would close their statement by vindicating their understanding of any social justice issues, for example, by pointing to, or mentioning a Nelson Mandela painting, or quote or screensaver.)

If it’s the latter of those two, what change are we talking about exactly?

And while we’re on the subject of Mandela, let’s not forget that there is, of course, such a thing as the right kind of black leader. And by that, I mean the kind that some white South Africans would be more willing to accept. Most of these, history has taught us, were perhaps once not so acceptable before. They were rebels, anarchists, communists, your general variety of societal pot-stirrers, or just … too black.

But with time, and pop culture of course, they have become very appealing to some of the white demographic. (Where were you when the deal was going down?)

Maimane has dabbled in the discourse of Martin Luther King, Mandela (the ultimate messiah to the white South African citizen because most of the time, that’s their only knowledge about black South African history) and, of course, Barack Obama – iconic black leaders who have been gifted popularity with the test of time.

In many instances, their images so clearly juxtaposed against his, that it feels like if he sells himself on their ideals, he won’t ever have to scare anyone away with his own. Many supporters have just eaten this up. Consumed it, without thinking critically about what they’re being asked to consume. “The Obama of South Africa” and all that.

Perhaps that responsibility of thinking critically does not lie with the consumer. Perhaps it lies with Maimane himself. And instead of feeding the public, his public and a public he certainly hopes to appeal to, some recycled version of a heroic black man’s words – something he still needs to prove himself to be, he should feed us his own.

If nothing else, Maimane is where he is because he needs to change people’s minds. And to do that, he needs to rip off the label that says “white owned”.

Without that, the only people he will continue to appeal to, are the ones who probably have coffee table books of the world’s greatest speeches.

“The revolution will not be televised,” wrote Gil Scott-Heron, known to many as the father of hip-hop.

The lyrics of the song, released in 1970, are built on a strong foundation of taking a stand against American consumerism.

Using intelligence and humour, it aims to inspire the listener to think critically about what they’re being asked to consume and what is being offered to consume.

Scott-Heron explained that revolutions are not for public consumption because they don’t broadcast what needs broadcasting.

So they take place in our minds. He said that revolutionary people understand that something is wrong and they can make it better, and so, they do. They effect change.

In the South African context, and with reference to Maimane’s victory revolutionising the DA’s representation in terms of leadership, the revolution will also not be televised.

But if Maimane does not effect change by refusing to be the token in a racially segregated system, then he will find himself in photos, on paintings and in posters that are hung on walls, in all the wrong houses.

(And as for all the chirpy conversation that’s going around comparing Maimane and Mandela. Just. Don’t.)