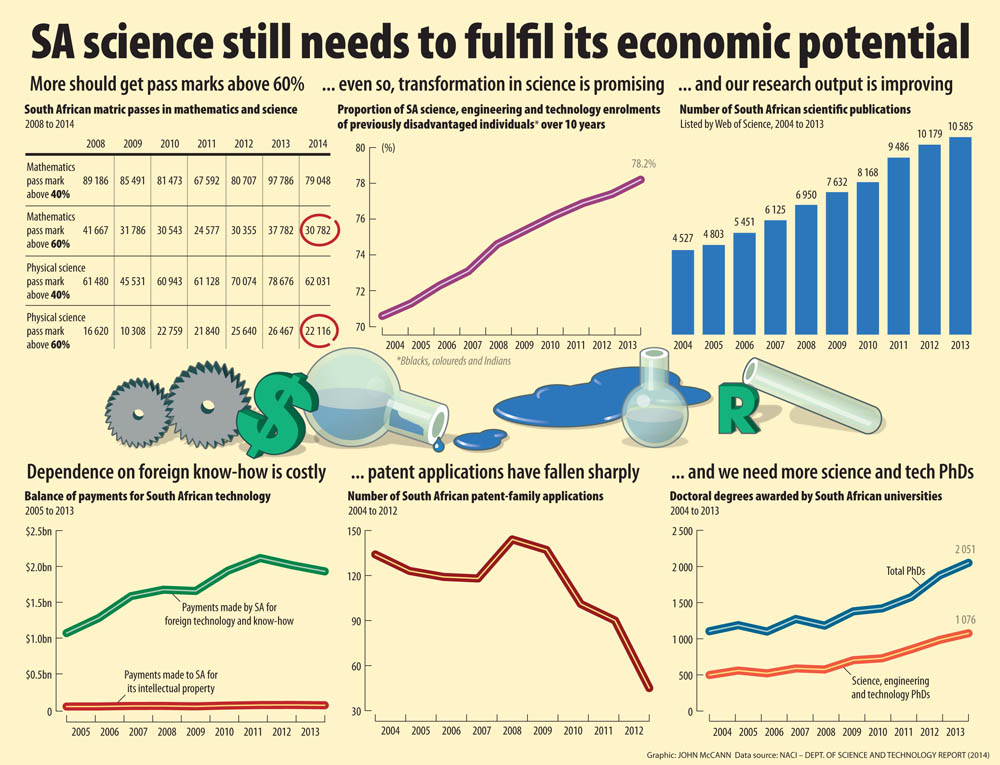

Only 2.5% of the pupils who started school 12 years ago achieved more than a 60% pass in mathematics and just 1.6% achieved a 60%-plus pass in science.

Each year, more than R20-billion leaves South African shores in technology payments, but the receipts we receive for our technology amount to less than R100-million, a situation specialists say is unsustainable.

The Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators 2015, published by the National Advisory Council on Innovation (NACI), paint the picture of an innovation system whose inputs are increasing – both in terms of money and students – but “doesn’t seem to be providing benefit in terms of ‘bang for your buck'”, says Azar Jammine, project leader for Naci monitoring, evaluation and indicators, and director of Econometrix.

In 2013, we imported $1.9-billion worth of technology and received only $63-million. Yet the amount South Africa sends offshore for technology has increased significantly in the past nine years. “If you keep importing more than you are exporting, you have this balance of trade deficit,” he says, “and you become more and more reliant on foreign exchange.

“The more you innovate, the more competitive you should become with your peers. It enhances the ability of your country to export more with its own facilities, and not rely on imports to keep the economy going.”

The deficit between our technology exports and imports “is one of the largest anywhere in the world. It means we are dependent on the whims of international investors,” Jammine says.

Innovation has been shown to increase international competitiveness, create jobs and promote economic growth.

Patent numbers

The government, through the department of science and technology, is pushing research and development (R&D), but it is not getting the outputs it expects in balance of payments and patents.

South Africa’s patent numbers continue to decline, according to the 2015 indicators. The number of patent family applications, which is a single patent or invention filed in different countries, went from a peak of 144 in 2008 to 45 in 2012.

In contrast to this, the number of doctoral candidates produced in South Africa has risen, including the percentage of candidates from previously disadvantaged backgrounds. In 2004, 1 105 people qualified with doctorates. This rose to 2 051 in 2013. Doctorates earned in science and technology subjects have increased from 499 in 2004 to 1 076 in 2013.

The number of academic publications and citations has also increased – from 4 527 in 2004 to 10 585 in 2013.

Claire Busetti, a member of the NACI, says: “We have been punching above our weight in R&D, but our scorecard in converting [this research] into products and services is disappointing to below average.”

Adviser to the minister

The NACI, which includes the likes of Standard Bank chief executive Sim Tshabalala, executive chairperson of Dimension Data Middle East and Africa Andile Ngcaba and Human Sciences Research Council chief executive Professor Olive Shisana, acts as an adviser to the minister of science and technology and the government, indicating what needs to be done to increase the efficiency of the national system of innovation and its outputs.

Asked what can be done to improve the system, Jammine says: “The greatest economic threat to South Africa is our education system.”

In a presentation of the results in Pretoria last week, Jammine said that, of the pupils who started school 12 years ago, only 2.5% achieved more than a 60% pass in mathematics, and 1.6% achieved a 60%-plus pass in science.

“You cannot get entrepreneurship going unless you improve the throughputs in maths and science. If you cannot count, it is difficult to become a successful entrepreneur.”

Additionally, “you need less government regulation that stifles attempts at entrepreneurship”, Jammine says, citing the recently promulgated black economic empowerment regulations and increased taxation in the form of e-tolls, carbon taxes and vehicle leasing taxes.

“Those kinds of interventions are making it less attractive for people to innovate.”

Small business bolstering

The third innovation-bolstering action he recommends is more government interventions to foster small business, rather than big business.

Big business’s reticence to carry out R&D is a source of major concern for players in the innovation space, and has been cited as an important factor that hamstrings innovation in the country.

According to the 2012-2013 National Survey of Research and Experimental Development published last year, 2012-2013 heralded a watershed for South Africa’s national system of innovation.

Although business does most of the R&D in South Africa, the government spent more money on R&D than business, mainly through institutions of higher education.

This means a number of the department of science and technology’s interventions focus on coaxing big business back into the space.

But Jammine says small business is “where you’re seeing the stifling of a lot of innovation”.

Aware of the concerns

Science and technology director general Phil Mjwara says his department is aware of the concerns raised by the indicators.

“The success we’re seeing in know-ledge generation [the number of science, engineering and technology students and postgraduates, as well as the number of publications] is because of interventions made in 2003 and 2004, such as the centres of excellence and research chairs,” he said.

“On the input indicators, we’re not doing badly, but [we’re aware of the shortfall in] the utilisation of research and its socioeconomic impacts, patents, technology balance of payments, investment by the private sector.”

But Mjwara points to the “output” interventions that the department of science and technology implemented in 2008: the Technology Innovation Agency and the National Intellectual Property Management Office as well as tax incentives for business R&D.

“Invention disclosures are up,” he says.

“Give us two or three years [the same lead time as the publication and PhD outputs], and you’ll see those outputs going back into the system.”