Kwashibu Area Band sees Pat Thomas revisit his 1980s heyday.

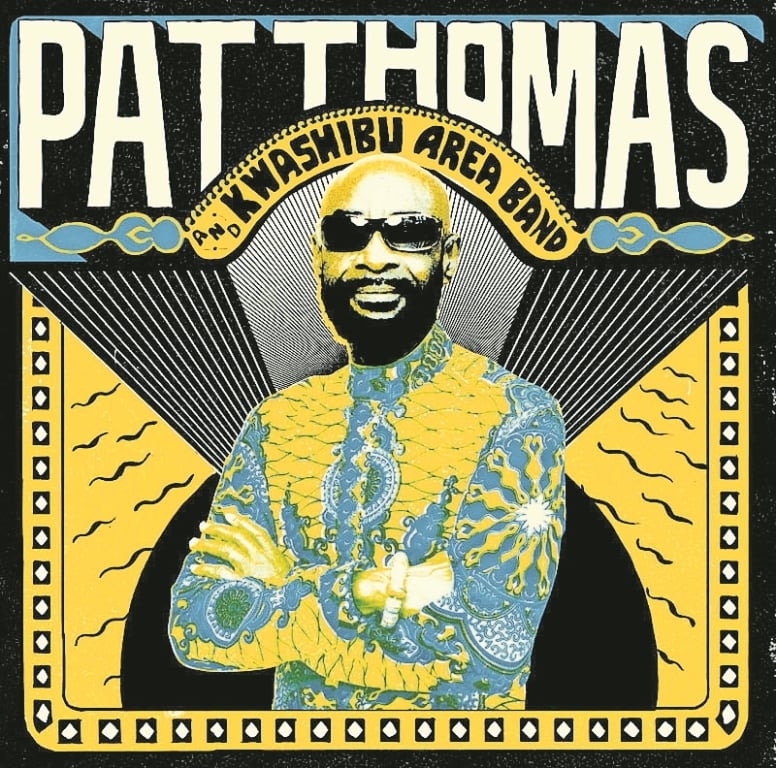

KWASHIBU AREA BAND by Pat Thomas (Strut Records)

Ghanaians must feel a bit left out when it comes to Afrobeat. People often forget that Ghana, not Nigeria, is where it all started; this was the place where traditional African rhythms first combined with European brass, an essential mould for the sound later popularised by Fela Kuti.

It may have been given a different name – highlife – but the roots of Afrobeat are obvious. Kuti performed in Ghana before his successes in his native Nigeria, and so the highlife movement of that time was key to his resulting explosion on to the world music scene.

But highlife is far more than a historical building block. Pat Thomas, dubbed the “Golden Voice of Africa” by a generation of enthusiasts, saw it change in accordance with the new sounds Ghana was being exposed to.

“Highlife was our music,” says Thomas of his interpretation. “People like [guitarist] Ebo Taylor and I modernised it, and made it more relevant to our day. We took the Kwa music of Kumasi and other local styles and added Western elements.”

The genre is alive, well and constantly evolving, and exists as a distinct African sound that should put its Ghanaian superstars – Taylor, Thomas and George Darko – on a similar pedestal to their Afrobeat counterparts.

The differences between the two genres are subtle; if you want to get technical, highlife emphasises the first, second, third and fourth beats, whereas Afrobeat focuses on the first and third with an exaggerated bass drum. This gives Afrobeat a funky swagger, whereas highlife comes closer to big-band jazz.

In terms of lyrical themes, Afrobeat is defined by the kind of government resistance that frequently got Kuti behind bars.

To understand the highlife attitude that gives the genre its swelling optimism, you have to look back at its roots. Ghana in the late 1950s was celebrating independence and the party atmosphere was relentless. Often summarised as a neocolonial totem, highlife saw the cosmetic brass bands of British-owned Ghana play their indigenous tunes for the first time. West Africa was rocking and life was in high spirits.

Thomas, whose new highlife album will be released on June 16, has kept the party going throughout his career. Hailing from the city of Kumasi, Thomas teamed up with Taylor at the age of 16 in pursuit of a breakthrough. Both would become stalwarts of the 1970s and 1980s highlife scene. Friends joked that you could always tell what Taylor would be wearing tomorrow from the clothes Thomas wore today; the two lived in each others suitcases, and Taylor had keen eyes and ears for the trends set by the man 15 years his junior.

Kwashibu Area Band sees Thomas revisit his 1980s heyday, re-recording hits such as Gyae Su, Odoo Adada and Mewo Akoma in his distinctive flowing vocal style sung in Ghana’s Fante and Asante Twi dialects.

Taylor again features on horn arrangements, completing highlife’s indisputably great partnership. A new big name comes in the form of Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, whose appointment as Fela Kuti’s pacemaker of choice surely still makes him a genuine contender for the best drummer in the world; that aforementioned Afrobeat swagger is definitely here, with shakes, whacks and percussive scrapes completing a rich backbone of rhythm.

At times Kwashibu Area Band is the Tony Allen show, with all nonpercussive instruments being stripped away to leave a pumping drum solo to remind us how tightly he’s been pulling everything together.

This release also celebrates the emergence of burger-highlife, a scene that came from the relocation of numerous Ghanaian musicians to Germany following a 1978 coup d’état that crushed Accra’s music industry overnight.

Thomas enjoyed a second career boost by recording in Berlin and Hamburg, and Allen’s split from the Fela Kuti entourage over a pay dispute made him the burger-highlife drummer of choice.

Germany was experiencing a digital music revolution of its own, and the electronic keyboards, simple disco beats and quality recording equipment gave highlife’s most exciting branch a rework that further distanced it from Afrobeat.

The co-operation between the two countries has continued, with Kwashibu Area Band being recorded and mixed in both Accra and Berlin. Germans such as the saxophonist and co-producer Ben Abarbanel-Wolff feature alongside both vintage and new generations of Ghanaians, epitomised by a crackling vocal appearance by Thomas’s daughter Nanaaya.

But Kwashibu Area Band has also managed to resist Germany’s digital revolution that seemed at odds with the brass-heavy heart of highlife, as Abarbanel-Wolff explains: “By the mid-1980s the heyday of ‘the golden era’ was over. With this album, we wanted to continue the tradition of the late 1970s sound and bring the roots of highlife back.”

The real joy in this album comes in the fact that Thomas, Taylor and Allen are no longer making music with a financial incentive. Their status as legends is set in stone, making Kwashibu Area Band contemporary with its slick production values yet staying true to highlife’s roots.

For a heady education into why Ghanaian music is great, look no further. Nothing has been sampled here, and so each track has a genuine buzz rarely found in modern bands of this scale.