Curator Natasha Becker is back in SA

“You know Mom, on the subject of boys and liking them: I don’t really,” Jocelyn Tremblay tells her mother hesitantly. “We like girls,” her twin sister Natalyn says, elaborating on Jocelyn’s revelation.

The Canadian siblings, dressed in similar clothes – grass-green T-shirts, blue waistcoats and grey pants – are shown on screens alongside each other, and are reminiscing about coming out queer to their mother and each other at the end of high school. Titled Tremblay Factum (2009), this video installation – part of the group show Speaking Back at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town – is part of South African artist Candice Breitz’s collection of interviews with twins, titled Factum.

The twins recall walking down a country lane with their mother when they broke the news. Natalyn says their mother “kinda giggled to herself and said, ‘I know’, and it was that easy”, and Jocelyn acknowledges that “as far as coming-out stories go” theirs “is a really good one”.

Coming out as gay, bisexual or transgender is significant in societies where heterosexuality is the norm. Unlike the positive reception accorded the Tremblay twins, in some parts of the world being open about your sexuality is met with imprisonment or violence.

Through another passage of the gallery, a video installation by artist/LGBTI activist Adejoke Tugbiyele exhibits the other spectrum of coming out and the outrageous reactions it may provoke. “You could have waited until I was dead,” Tugbiyele’s mother demands in the artist’s performative video piece AfroOdyssey V: Demons Contained (2014). This reaction is not that uncommon. Nor is coming out after a parent dies. Kenyan activist, writer and close friend of the art world Binyavanga Wainaina did exactly that on his 43rd birthday last year, publicly coming out after his mother died.

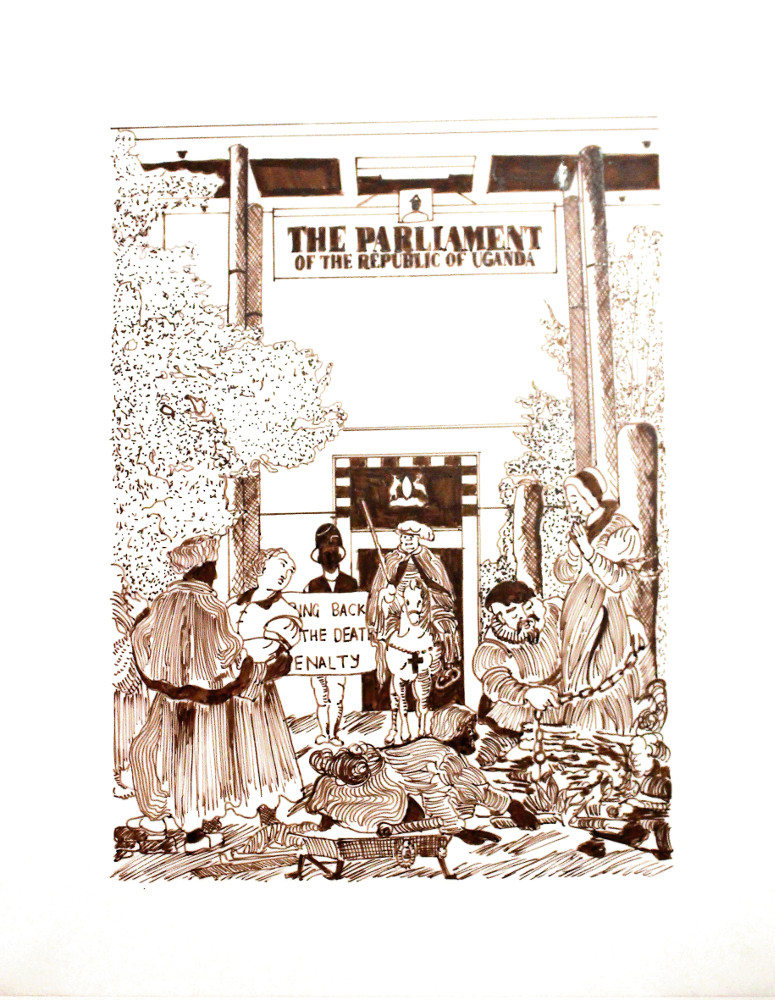

Adejoke Tugbiyele’s Bring Back The Death Penalty

Of the solo performance piece Tugbiyele, a United States-based Nigerian sculptor and artist, says: “I play my mother, my father and myself. I revisit that traumatic moment when I come out face to face to my Nigerian parents in their Brooklyn, New York, home.”

When I ask Tugbiyele – whose work on Speaking Back includes ink drawings, a sculpture and a performance art piece that she did on opening night in May – what issues she’s speaking to in the show, she says: “The reality of death, torture, pain, jealousy, fear is so real among many LGBTI Africans. Many people don’t realise that the coming-out experience is torture enough!”

It’s these varying female perspectives on topics ranging from politics to gender identity and religion that weave together the artistic narrative in Speaking Back.

“Talking back to race, culture and gender as well as history is a constant theme for me as a curator, hence the title Speaking Back,” Natasha Becker says of her new show at the gallery, where she has recently been appointed senior curator. “I wanted it to be active, and for people to ask: ‘If they are speaking back, what are they saying?’ I wanted it to be about what women artists are saying when they speak about race, queerness or even imagination.”

The gallery is dim. Visuals project off its white walls. A sculpture drapes from its ceiling. Prints are mounted. It’s a peculiar exhibition, one in which both haunting dreams and daydreams are played out in artistic expression. A naked, soiled body moves eerily back and forth against a backdrop of names of freedom fighters in South African artist Tracey Rose’s projection, The Black Paintings: Dead White Man (2012).

US artist Kara Walker’s shadowy video, Fall Frum Grace, Miss Pipi’s Blue Tale (2011), mixes the story of slavery with a German expressionist aesthetic and Arlene Wandera’s dollhouse structure, I’ve Always Wanted a Doll’s House (2010), according to Becker, “is supposed to be about an idealised childhood, yet the sculptures on and in it are quite dark”.

In between these saturnine images that broach topics such as subjugation and prejudice, the room is filled with art that flirts with fantasy and folklore, yet remains poignant and topical. A large, ethereal print in muted tones by Nigeria’s Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze, with an equally whimsical title: With the Galaxy Beneath Her, She Remembered the Magic of Soaring Amidst Coconut Clouds (2014), catches the eye when you step into the gallery. Renowned Egyptian-born artist Ghada Amer’s abstract piece, Dreaming of Felipe-RFGA (2010), looks romantic yet melancholic; like unrequited love.

“It’s about imagination and the right of black women artists to imagine, and the power in that,” Becker says of some of the more metaphorical pieces on Speaking Back. “Ruby Amanze’s drawings are all about imagination. But she has to fight for a place for that too because it relates back to the expectations we project on to artists. Her work really makes us think of that and why is it that young women artists have to justify making objects that are about imagination and beauty.”

And it’s with this feminist approach that Becker has pieced together Speaking Back. “What’s been great about this show is to have artists who feel really proud to be able to speak through their work and to be acknow-ledged for the message that they are communicating or the experience that they are sharing,” says Becker, born in the Cape Town suburb of Retreat, but sojourning in the US since 2003 in pursuit of a doctorate in art history. While there, she cofounded the International Video Art Festival in Greenfield, Massachusetts, which took place for a few years.

Natasha Becker. (Photo: Madelene Cronje)

Becker says she’s been working on Speaking Back for almost a year after meeting Goodman director Liza Essers at the Frieze Art Fair in New York last year. “When Liza invited me to do a show, I knew I wanted it to be on women artists in Africa and the diaspora,” she says.

“I have been thinking for a long time about women artists, because my research when I started my PhD was on the Johannesburg biennales and it was on contemporary South African art at the moment, and I looked at the biennales as a site for that.

“And there was a big debate during the second biennale around women artists, the black body and representation. So this has always been something I’ve wanted to go back to, that question and issue. So as a kind of follow-up research project, I wanted to look at women artists since then.”

Becker has recent and vigorous experience of working with female artists and their perspectives. For collective curator-driven Spring/Break Art Show in New York last year, Becker’s curation explored the sociopolitical landscape of her native country with the work of South African artists such as Dineo Seshee Bopape, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi and Zanele Muholi.

Fast forward to Speaking Back, and Becker widens the geographical looking glass using the perspectives of women artists from Africa and the diaspora; a perspective that is still marginalised within the male-dominated art world. “I think there are lots of limitations on women’s creativity, so part of what we have to do is remove those limitations,” Becker says.

“There are many different kinds of feminists and women subscribe to different kinds of feminism but, at the heart of it, this show is about supporting women’s rights and creating opportunities for women.”

Speaking Back is on at the Goodman Gallery in Woodstock, Cape Town, until July 18. Stefanie Jason’s trip to Cape Town was sponsored by the Goodman Gallery