The African Union’s renewed hostility towards the International Criminal Court (ICC) might cause a diplomatic headache and earn it hash criticism from the developed world, but it is unlikely to hit the body financially.

The AU receives about two-thirds of its funding from donor countries, with many of its own member states lagging behind in paying their fees.

One of the primary criticisms the AU has of the ICC is that it is funded by Western powers.

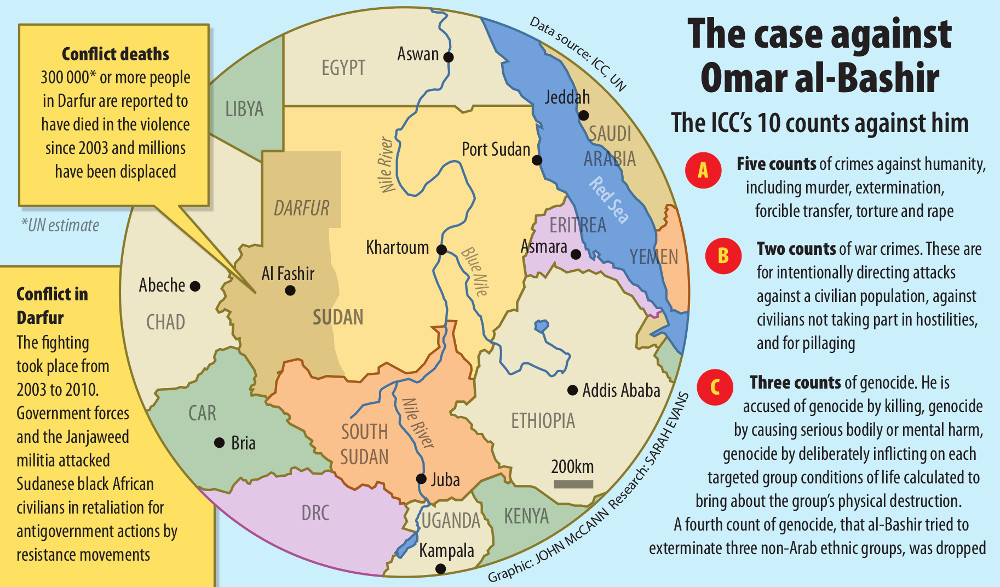

This week some of those donor countries appeared quietly appalled by the escape of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir from South Africa, and the sabre-rattling by many AU countries about the ICC.

Frank Oberholzer, spokesperson for the European Union embassy in Pretoria, said the EU-AU partnership was reaffirmed last year and the relationship “is not directly affected by questions relating to the ICC”.

Bound by ICC decisions

But he said the EU “strongly supports” the ICC and that the court’s member states are bound by its decisions. “The rule of law is not overruled by decisions of the AU,” he said.

“Incidents of nonco-operation [with ICC] state parties are breaches of legal obligations with all other state parties, including all EU member states, and are treated as such. The ICC cannot fulfil its mandate without full co-operation by Rome Statute states parties. The EU and its member states react accordingly to instances of nonco-operation.”

But the US took no view on the AU’s stance on the ICC in response to questions this week. The US is also not considering withdrawing its support to the AU over its stance on the ICC. This is according to Jack Hillmeyer, the US Embassy spokesperson in South Africa.

“The United States strongly supports the AU’s growing involvement in promoting democracy and human rights, supporting economic growth, preserving peace and security, and advancing opportunity and development. These goals closely align with President Barack Obama’s strategic objectives for Africa,” Hillmeyer said.

Analysts believe the AU’s stance on the ICC is unlikely to cost it financially. “This is not a new position of the AU,” Ottilia Maunganidze, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, told the Mail & Guardian this week.

“This is a position that they’ve held since 2009 when al-Bashir’s first warrant of arrest was issued.” Since then, he has travelled to Kenya, Chad, Nigeria and now South Africa, without being arrested.

These countries were at the receiving end of a verbal whipping from human rights groups and the ICC itself, but earned only mild statements of “disappointment” from the likes of Britain. No country publicly threatened to punish the AU economically.

Unchanged situation

Al-Bashir was due to travel to South Africa in 2009 to attend President Jacob Zuma’s inauguration, but did not. At the time South Africa knew it would have to arrest him, Maunganidze said. The legal situation has not changed.

Even if donor countries were to use their financial muscle to express their displeasure at the AU’s attitude to the ICC, those countries would have to consider the broader impact – including on countries that have co-operated with the court.

Former Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) commander Dominic Ongwen was surrendered to the ICC with the co-operation of Uganda and the United States, Maunganidze pointed out. Uganda has offered to help the court in its attempts to prosecute Ongwen as well as with tracking down LRA leader Joseph Kony.

“A key point is that, while the AU criticises the ICC for getting funding from the EU and other countries, the AU also receives funding from many of those countries,” she said.

“The difference is that the ICC only receives funding from countries party to the Rome Statute,” she said.

Policy considerations

Donor concerns seem less focused on the ICC and more on how the AU uses the money it receives, and to what extent its lack of self-funding influences policy. A report from an international colloquium on the AU’s progress, held in Germany and hosted by the Centre for Conflict Resolution and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung in 2012, mentioned precisely this matter.

“The issue of funding for the AU may be less important than how that money is spent and the political will of African member states to strengthen the union,” it states.

A report compiled by Ulrich Karock of the European Parliament raised similar concerns about the AU Peace Fund.

“With international donors funding most of the [peace fund] – with the conditions usually attached to such funds – the fund seems not to represent an effective ‘African solution to African problems’. Furthermore, questions have been raised about its economic governance framework and the need for … adequate accountability,” he wrote.

There were also concerns about the AU’s response to the crisis in Mali, which “laid bare the inefficiencies of the funding and resourcing of AU peace support operations”.

Budget hopes

The AU is hoping for a budget of more than R6?billion for 2016, and says its development partners “will remain key to the financing of programmes and projects”. These partners are expected to contribute 69% of the total budget for next year.

Alfredo Tjiurimo Hengari, a senior fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs, told the M&G there was little chance that the AU would lose funding as a result of its stance on the ICC.

“There has been a long-standing standoff between the AU and the ICC. We’ve not seen Western countries expressing themselves on the AU’s stance,” he said.

Hengari said the push for an African pull-out from the ICC was “much stronger” in 2013, when Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta was to be prosecuted.

“That really offended many, many Africans. In a number of capitals the question of al-Bashir is possibly divisive, but the question of Kenyatta clearly illustrated the degree of concern that African countries were being targeted. They saw Kenya as a democratic country, unlike Sudan. So when the people of Kenya expressed themselves in favour of Uhuru, the people had to be respected,” he said.

Asserting independence

Hengari said African countries have been asserting their independence from former colonial powers, and the interest from emerging powers such as Turkey, Russia and China will make Europe “think twice” before divesting from the AU.

“Emerging powers have come to Africa almost without any conditions. In that context, they are displacing European hegemony.”

Hengari also believes that China, as a major funder of the AU, would consider its economic interests in Africa over whatever moral views it may hold on an issue like the ICC.

“China has not signed the Rome Statute. So, for China, the ICC question is a nonissue. China’s position on Sudan for a very long time was about economics and access to oil resources.” – Additional reporting by Mmanaledi Mataboge