Double standards: South Africa has a very progressive Constitution that

While talks in the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac) on a national minimum wage regime proceed, presentations to Parliament underscore the starkly different approaches of business and labour.

The first round of Nedlac discussions are expected to end in August.

Labour is pushing for a “medium-term strategy” to improve the income of low-paid workers and bring the value of minimum wages closer to the level of average South African incomes. This is according to a presentation by union federation Cosatu to Parliament’s portfolio committee on labour last week.

The strategy is intended to avoid either a minimalist approach, which would set a national minimum wage too low, or a “maximalist” approach that would risk deadlocking negotiations and result in an unfeasible jump from current wage structures.

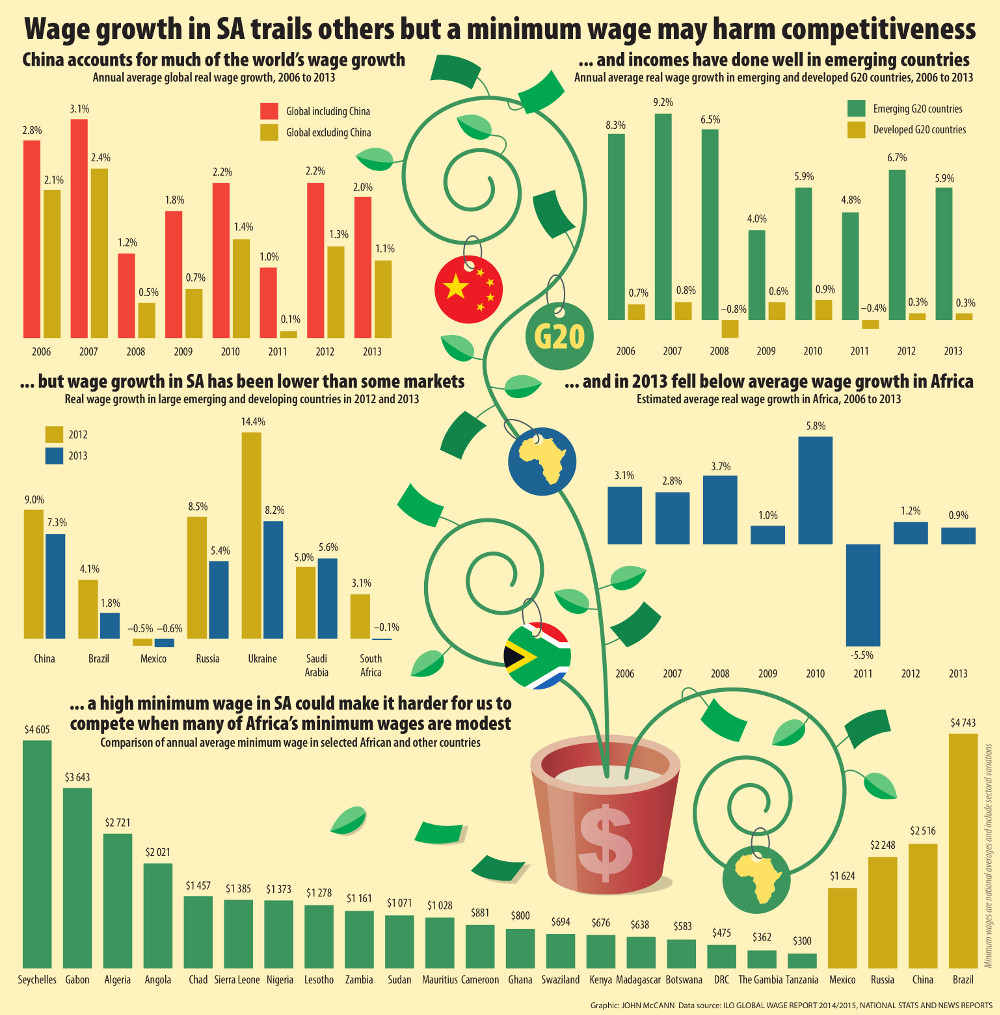

Cosatu calculated in 2014 a worker needed to earn R946 per family member or at least R4 730 per month to protect their family against poverty, a figure much larger than all monthly sectoral determinations for minimum wages set by the labour minister on the employment conditions commission’s recommendation.

According to research by Cosatu between 2007 and 2010, after the introduction of higher minimum wages through sectoral determinations, net employment in the affected sectors by over 650 000 workers rose from 3.45-million to 4.1-million, despite the loss of farming jobs.

Later statistics seem to contradict this, said Cosatu’s Neil Coleman, who delivered the presentation.

Data from 2015 suggested, despite farmworkers’ strikes in 2012 and a 50% rise in the minimum wage in 2013, employment numbers in agriculture increased by 195 000 between 2012 and 2015’s first quarter – 22%.

Low, declining wages didn’t create jobs, he argued: real wages of low-skilled workers had fallen since the 1990s, but low-skilled jobs had dropped by nearly a million.

At the same time 2.5-million jobs were created for higher-skilled workers over the same period, despite a large increase in real wages, he said.

The experience of introducing national minimum wages in other developing countries has not been as destructive as critics originally thought, said Cosatu. It said in Brazil, where fears that a minimum wage would have negative impacts did not materialise. Instead, between 2002 and 2013, inflation fell, while unemployment declined to below 4% for men and 6% for women in 2013.

Levels of public debt declined from highs of over 60% per gross domestic product in 2002 to around 35% in 2012. Formality in the labour market increased, as did unionisation among low-paid workers.

But business groups have argued that, given the adverse economic climate, institutionalising a minimum wage is unwise.

The South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s acting chief executive, Peggy Drodskie, said in a submission to Parliament that a minimum wage in South Africa risked an adverse effect, particularly on small and medium enterprises.

Comparing studies on the effect of national minimum wages was “superficial, at best”, said Drodskie, as they couldn’t be taken “out of the context” of individual regions’ circumstances. In the Brazilian example, business prospered to an unprecedented degree, raising job creation. In this environment, a national minimum wage was useful: enhanced prosperity could be “more widely distributed than might have been the case otherwise,” she said.

Circumstances in Brazil had changed “for the worse,” she said. “The [national minimum wage’s] value might be open to question.”

She said that in Thailand, introducing a minimum wage in 2012 caused an increase in inflation of 1%, a 1.7% drop in GDP and a 5.5% drop in employment.