Greece has been making headlines

The global response to the most recent worldwide financial crisis was to push debt levels to new heights, laying the ground for the next crisis.

This is according to a July 2015 report by the Jubilee Debt Campaign, a British-based lobby group for freedom from debt in developing countries. It identified 95 countries at risk of, if not already in, a debt crisis. South Africa – often lamented as having a worryingly high debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio – was not one of them.

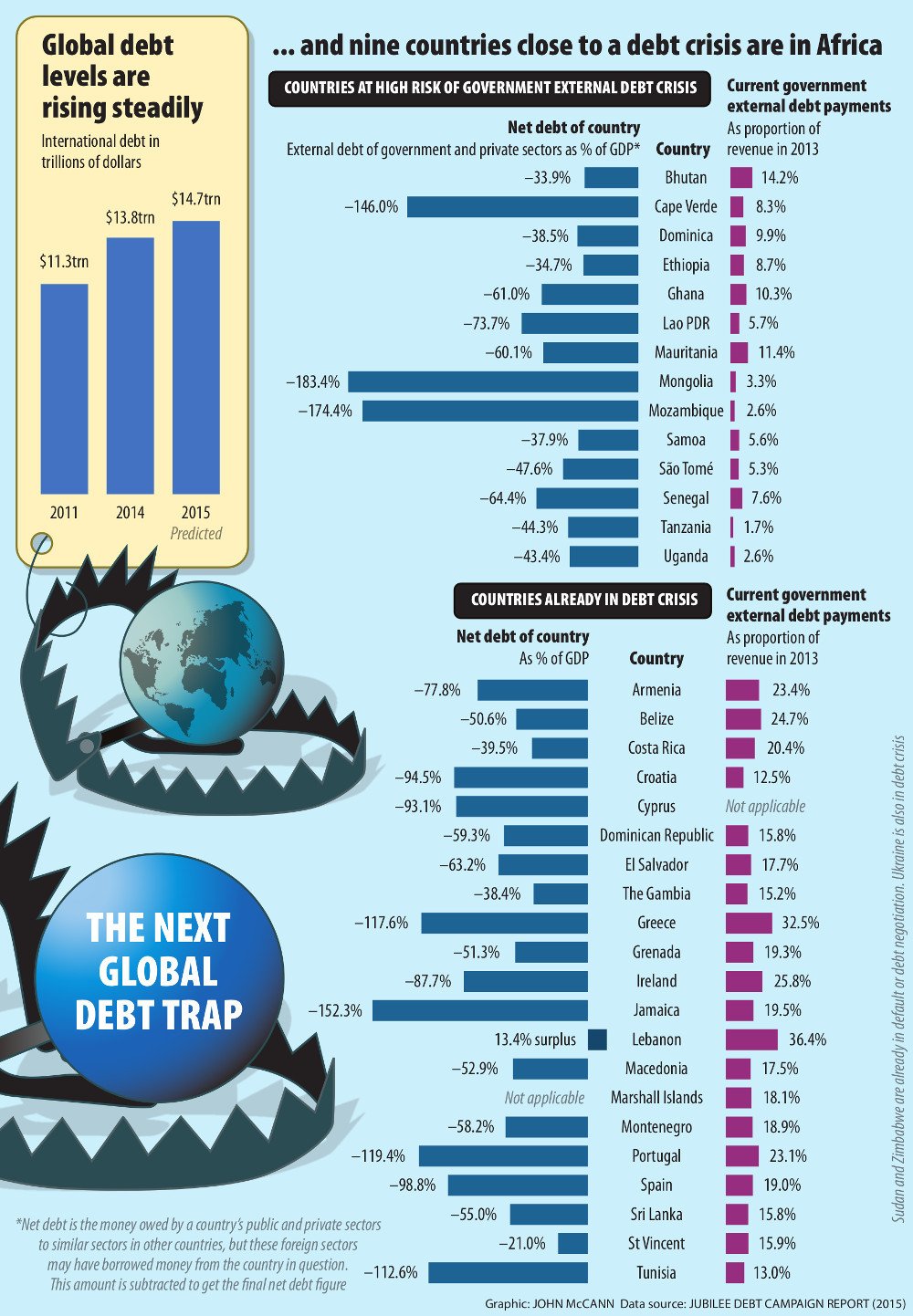

Debt crises have become more frequent across the world since the deregulation of lending and global financial flows in the 1970s. After falling from 2008 to 2011, international debt has been increasing since 2011. Total net debts owed by debtor countries, both by their public and private sectors, which are not covered by corresponding assets owned by those countries, have risen from $11.3-trillion in 2011 to $13.8-trillion in 2014. This, the Jubilee Debt Campaign predicts, will increase to $14.7-trillion in 2015.

The increase in debts between countries is driven by the largest economies. Of the world’s 10 largest, eight have sought to recover from the 2008 financial crisis by borrowing or lending more, thereby further entrenching the global economy’s imbalances. China and Brazil didn’t.

“It seems the lessons of the financial crisis and the danger of these global imbalances hasn’t been learnt. Current patterns of global trade and finance are sowing the seeds of the next global crisis,” according to Jubilee’s report, The New Debt Trap.

High-risk countries

Developing countries are at the highest risk. The report identified countries either in a debt crisis or most at risk of becoming one. This was done by looking at countries’ total net debt in public and private sectors, future projected government debt payments and the ongoing income deficit or surplus countries have with the rest of the world.

The Jubilee Debt Campaign noted in a release that debt burdens in the most impoverished countries are increasing, 10 years after the G8 summit in Gleneagles committed to cancelling developing country debts. Of the 95 countries listed in the report as being in or at risk of a debt crisis, low-income countries featured prominently. Of the 14 countries identified as being at high risk of falling into a debt crisis, nine are in Africa. These are Mozambique, Ethiopia, Ghana, Uganda, Tanzania, Senegal, Mauritania, Cabo Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe.

South Africa, with a debt to GDP ratio of 39% in 2014, did not appear anywhere on the Jubilee Debt Campaign’s radar. This is because the report measured external debt as its key indicator and not internally generated debt. South Africa is classified as an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank.

In South Africa’s case, external debt as a proportion of GDP was estimated at 15%. For comparison, Brazil’s was 5%, Turkey’s was 11%, Australia had external debt accounting for 14% of GDP and the United States’s accounted for 37%. Greece, which defaulted on its loan repayment to the European Union at the end of June and faced an exit from the eurozone, has external debt that represents 178% of its GDP.

Tim Jones, an economist for the Jubilee Debt Campaign and author of the report told the Mail & Guardian external debt was a more important measurement to detect a country’s risk of falling into crisis, as “debt owed inside the country is not typically a drain of resources”, he said.

Repayment cost

The repayment cost of external debt is important as the figure of total debt owed did not take into account interest rates attached to loans or the repayment period over which a country could settle, Jones added.

South Africa’s external debt repayments accounted for 4.7% of revenue in 2013. This compares favourably with estimated repayment of 5% of revenue in Britain, 5.8% in Sweden and 12.5% in the US. Greece’s repayments were estimated at 32.5% of revenue in 2013, Portugal was 23.1% and Spain’s 19%. Sudan and Zimbabwe don’t have high government debt payments but are already in debt crisis: they are in default on much of their debt and their overall debt is unpayable.

Mohammed Nalla, head of strategic research for global markets at Nedbank Capital, said South Africa’s total debt levels are not seen to be in crisis territory and are only projected to get close to 50% (in a worst-case scenario). As such, the absolute level of our debt is considerably lower than other geographies, he said.

Nalla said South Africa does not have a debt issue per se, but rather a deficit issue. South Africa’s status as a net importer is of concern because it exacerbates the deficit problem, of both its fiscal and current accounts.

“Our spending patterns, resulting in a fiscal deficit, are currently unsustainable and, as such, raise the question around our ability to service our outstanding debt as well as any additional debt burden,” he said. “This is of primary concern to ratings agencies. While this can be addressed through fiscal reforms, they do take some time to take effect.”

Imports and exports

South Africa remains primarily a net exporter of low value-added primary products, such as commodities, and an importer of higher value-added products, coupled with a relatively undiversified basket of export goods, leaving the country vulnerable to downturns in commodity cycles.

Deficits are not in and of themselves a problem if a sovereign state is able to fund these through domestic savings, said Nalla. However, South Africa is considered a chronic low saver, with a domestic savings rate at zero or low single digits and, as a result, it is heavily reliant on foreign capital flows to offset existing deficiencies.

According to Jones, the Jubilee Debt Campaign’s report makes use of debt sustainability assessments, produced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which predict future debt payments for low-income countries, countries that have recently moved from low-income to middle-income status, and small island states. Similar information for richer countries is not available.

Jones said the two institutions, as major creditors, have a clear conflict of interest when conducting such assessments. But they are the only assessments available.

The research findings showed that the countries most dependent on foreign lending have grown quickly, but their levels of poverty and inequality have generally been increasing.

Further, there have not been significant structural changes to their economies, such as a lower dependence on commodities, to make them more resilient to external shocks, and “high levels of lending mean that such shocks would be very likely to ignite new debt crises”, said the report.

Commodity prices

The recent fall in commodity prices means the loss of expected export income. It has caused currency devaluations, which increased the relative cost of debt payments made in foreign currencies.

The Jubilee report estimates Ghana’s currency devaluation will cause its foreign debt payments in 2015 to grow to 23% of government revenue – versus the 16% predicted by the IMF and World Bank. This does not take into account a drop in government revenue from lower commodity prices.

Although many multilateral and bilateral loans come with lower interest rates than from the private sector, they are still denominated in foreign currencies such as dollars. Interest rates on the major currencies in which loans are issued have not risen yet as interest rates in the US remain as historical lows, but they are expected to increase later in 2015.

“This could dramatically affect the relative value of government debts in dollars, and countries’ ability to repay them,” the Jubilee report said.

The research found foreign loans to low-income country governments trebled between 2008 and 2013, driven by more “aid” being provided as loans. Unlike loans to middle- and high-income nations, loans to low-income countries are dominated by the public sector.

Financial aid

“Aid” loans from Western governments have almost doubled since the global financial crisis began – $9-billion in 2006 to $18-billion by 2013, when primary providers of loans classified as aid were Japan, EU institutions, France and Germany.

The reason for the increase in loans from these “aid” givers is loans enable aid statistics to increase, or at least fall less, while committing less money over the medium term, thus helping cut budget deficits, the report speculated. “Under current Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development rules, the whole loan is counted as aid in the year it is made.”

The report noted public-private partnerships (PPPs) are problematic.

“PPPs are currently thought to account for 15-20% of infrastructure investment in developing countries,” the report said, “but research suggests that PPPs are the most expensive way for governments to invest in infrastructure, ultimately costing more than twice as much as if the infrastructure had been financed with bank loans or bond issuance.”

Stopping the promotion of PPPs as a way to invest in infrastructure and services is one of a number of suggestions put forward in the report by the Jubilee Debt Campaign that could help to prevent future debt crisis. Other suggestions for concerned nations include: supporting cancellation of debts for countries already in crisis; regulating banks and international financial flows; supporting tax justice; and ensuring that aid takes the form of grants rather than loans, and that “aid” loans do not cause or contribute to debt crises.