Volatility continued to plague China’s market this week despite efforts by authorities to halt further declines in share prices.

But the record highs in Chinese stocks in the first half of the year were due for a correction, according to analysts, who believe that the government’s intervention has undermined the credibility of China’s commitments to market reform.

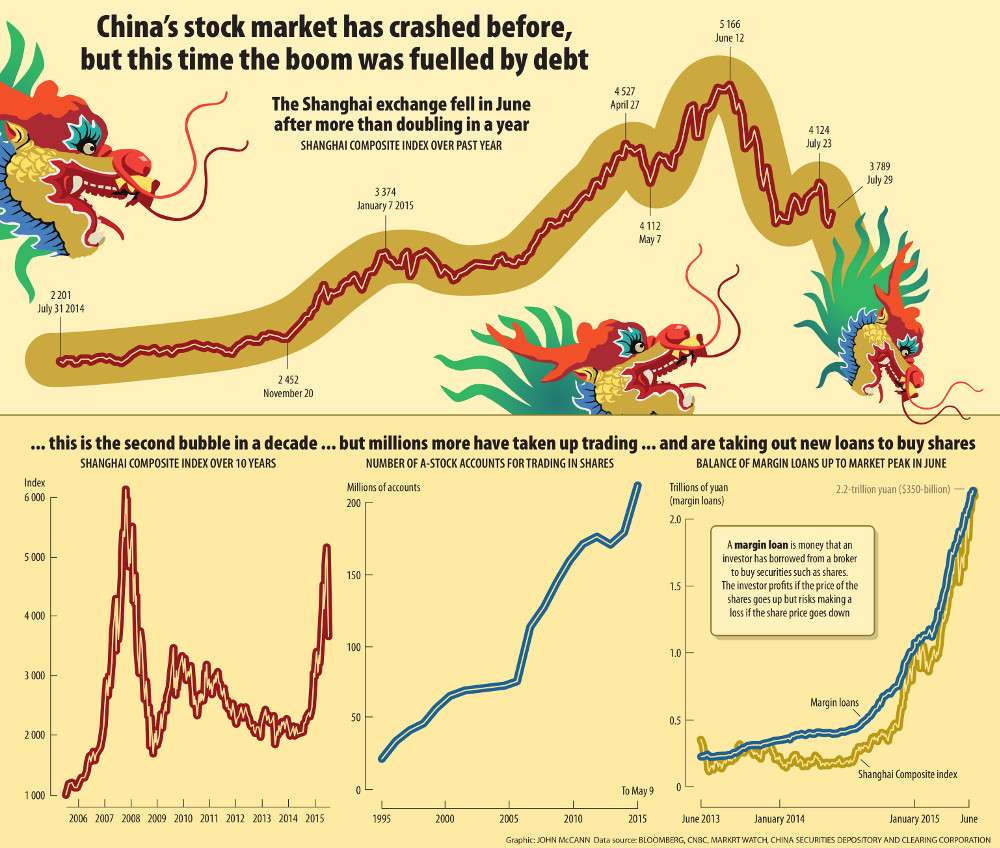

Jeremy Stevens, an international economist at Standard Bank, said, despite soft economic fundamentals, since January shares traded on two of the largest Chinese stock exchanges had reached record levels. The Shanghai composite index was up 54%, and the Shenzhen composite index was up “a staggering” 119%.

“Even though the timing of the correction was unknown, the fallback was a certainty.”

The government was concerned about the overheating market, margin trading (the use of borrowed money to buy shares) in particular.

According to Stevens, by the end of June, margin debt had increased fivefold from the previous year to reach 2.3-trillion yuan ($161-billion). Administrative efforts to curb this, among other things, spooked investors, especially large institutions, “who were keen to take profit that they knew didn’t reflect underlying reality anyway”, Stevens said.

The potential for harm from a fallout had also increased for a number of reasons. An additional 52-million stock accounts were opened in the first six months of the year, and a large number of companies had speculated on the stock market to fend off weak demand and falling profits, he said. Many pledged their shares as collateral for bank loans, and banks had been bundling loans into securities to make room on their balance sheets for more lending.

He added that the market correction, which began in earnest in early June, wiped out $3.3-trillion in 15 trading days.

Chinese authorities have introduced a range of measures to reverse the declines, which, according to a report by the digital business news publication Quartz, include bans on share trading, relaxing rules on margin financing, and allowing pension funds to increase their holding of equities to 30% of net assets.

Beijing’s intervention to prop up the market has implications for its reform agenda.

In a briefing note, the South African treasury’s international and regional economic policy unit said the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets had been key instruments in the shift towards what President Xi Jinping had termed the “decisive role of the market in allocating resources”.

The two markets had also been a mechanism for reforming China’s nearly 140?000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

The reforms included the conversion of state holdings into tradable shares together with increased oversight, enabling the SOEs to be market-ready when the conversions occurred, it said.

The SOEs are associated with slowing growth, falling productivity, unsustainable fixed asset investment, declining profitability and growing corruption.

The note highlighted that Chinese retail investors had fuelled the recent market growth, funding their trading with savings or loans.

“The unwinding of their positions could further depress global growth and weaken key markets, particularly commodities, through the further contraction of demand from China,” it said.

Stevens said, even if Beijing was able to stabilise the markets, “the victory has done lasting damage to the credibility of Chinese regulators when it comes to the reform agenda. From now, almost all utterances from the administration will be questionable.”

Chinese market volatility has come against a backdrop of slowing growth in the broader economy.

For the past four years, the Chinese economy had been losing momentum, according to Stevens. Fixed asset investment has slowed, and its debt burden had increased. Local government debt had doubled to 20-trillion yuan (R40.7-trillion) since 2009. A substantial amount of the debt was coming due in the next two years, and interest costs had become unbearable for some localities, Stevens said.

But efforts to address this did not solve the problem of China’s underfunded “fiscal economy”. Local government was responsible for 85% of expenditure but only received 50% of that from government revenues.

Stevens also flagged the rise in corporate debt, which has grown faster than in any other country.

“Of particular concern is the fact that nominal GDP [gross domestic product] growth appears to have dropped below the average lending rate, meaning that servicing existing debt will become more difficult,” he said.

The Chinese economy needed time to adjust to the changes brought about by its shift towards what was widely seen as a more consumer-driven economy. The country’s economic model was changing and new risks had emerged, he said.

“Gone are the days where simply mobilising mispriced resources [such as] land, labour [and] capital, can generate rapid headline growth. Even growth of 5% to 6% over the next five years will require constructive and smart reforms,” Stevens said.