Government is tightening up on reckless and unscrupulous lending, but a recent judgment in the high court shone the spotlight on law firms that collect debt yet are not subject to debt collection law or regulation.

When a creditor has exhausted all formal avenues to collect debt, their last resort is often to turn to the courts for an emolument attachment order (often erroneously referred to as a garnishee order) to deduct debt repayments from the debtor’s salary.

It is considered by the industry to be an effective tool for debt collection, but chronic abuse of the system has been a prominent cause of concern for some time.

The role law firms play in debt collection was highlighted in a case brought by Stellenbosch University’s legal aid clinic on behalf of 15 debtors who claimed attachment orders against their salaries had been unfairly obtained.

Many legal firms offer a debt collection service, but just a handful specialise in it. One such firm is Flemix & Associates, the 17th respondent in the Western Cape High Court matter and one of the biggest legal firms in the debt collection industry in South Africa.

Misused clauses

In his judgment handed down in the high court in Cape Town last month, Judge Siraj Desai found Flemix, and 13 other respondents it represented, had misused clauses in the Magistrates’ Court Act to obtain emolument attachment orders against these debtors. Debt collection agents working for the law firm were also found to have not followed procedure in getting debtors to sign consent to judgment.

The judge determined the loans had been extended recklessly by their originators because there was no evidence that affordability assessments had been done.

“These were quite obviously reckless loans and, unsurprisingly, the applicants defaulted on their repayments,” Desai said in his judgment.

As a result of the judgment, the National Credit Regulator has said it will investigate the 150 000 active cases on Flemix’s books.

Flemix says it has applied to appeal the high court matter.

Last resort

Emolument attachment orders are meant to be used as a last resort to force repayment from customers who ostensibly can pay their debt, but don’t.

“If a person makes a commitment and loses their sources of income, there is recourse in the form of formal remedies,” said Hennie Ferreira, chief executive of MicroFinance South Africa. “There is debt counselling, and you can put yourself into debt review, or legitimate credit providers will assist you before you even get into debt counselling.”

Thereafter a debtor may be handed over for so-called soft-collection by registered members of the Council for Debt Collectors, who are subject to rigorous regulation.

Soft collections refers to debt collection that does not go through the courts, but rather involves written requests or persistent communication from call-centre agents.

So clear are the regulations and limitations the council has a saying: “If you feel a debt collector has treated you unfairly, then what they have done is probably illegal,” said Andries Cornelius, the council’s chief executive.

Criminal offence

The council is a regulator created by statute that came into being in 2003 and has 17 900 registered members. To collect debt without being registered with the council, which falls under the department of justice, is a criminal offence. The council enforces compliance with regulations or debt collection and has the power to fine up to R100 000 per account, it can mete out suspended sentences, and it can even withdraw a member’s registration which makes it illegal for them to practise debt collection at all.

The Debt Collectors Act limits the fees a debt collector can charge to no more than the capital amount of debt or R814, depending on which is lower. Added to that, the debtor can be charged 10% on each instalment paid, although this, too, is capped at R407 per instalment.

By law, the council has to investigate each complaint it receives and can receive up to 7 000 queries a year.

“But of those we maybe find there are 100 a year we actually charge,” said Cornelius, who noted the issues tended to be largely administrative.

“In general there is a high rate of self-regulation in this industry,” Cornelius said. “It collects about R9-billion a year. [With those kinds of numbers involved] you can’t afford to have the council withdraw your registration.”

Soft collection services

Cornelius said some law firms are registered with the council and are subject to the Act’s limitations, but only insofar as soft collection services are concerned.

But when law firms collect debt through litigation, they are not compelled to be registered with the council. Instead, they are regulated by relevant law societies. There is also a lack of clarity about how legal fees and their limits are regulated.

The problem with collecting the debt through an attorney is the cost, said Jan van Rensburg, president of the Law Society of the Northern Province, which has been ordered by the Western Cape High Court to investigate the conduct of Flemix.

“The legal costs are basically the same, regardless of the amount owed,” he said.

For example, the legal cost may be R6 000 on a debt of R1-million, or R6 000 on a debt of R600.

“The problem is the work you do is the same,” he said. “There is no different scale applicable just because it is a small claim.”

Popular route

Obtaining an emolument attachment order is a popular route because it is obtained against the debtor for debt “plus costs”. Fees are prescribed by the law societies. For the Northern Province society, for example, a letter for demand cannot cost more than R50 and consultation with a debtor cannot be charged at more than R90 per 10 minutes. These can, however, quickly amount to significantly more than the fees prescribed by the Debt Collectors Act.

Further, there is some debate about whether the limits prescribed by the National Credit Act apply to fees charged by attorneys who collect debt through the courts.

In dispute is the in duplum rule. In common law it means interest stops running when the unpaid interest equals the outstanding capital. But the National Credit Act goes beyond this and states that accrued interest and fees, including collection costs, during the time a consumer is in default may not exceed the unpaid balance of the principal debt under that credit agreement.

The company secretary at the National Credit Regulator, Lesiba Mashapa, said: “The NCR’s view is that legal fees are part of collection costs and are covered by the NCA’s Section 103(5) in duplum.”

The Association of Debt Recovery Agents, of which membership is voluntary, was the 18th respondent in the high court matter. Marius Jonker, the association’s vice-president, said there is no straight answer about whether law firms doing debt collection adhered to the in duplum rule. There are two reasons for this.

Ongoing debate

First, there is an ongoing debate over whether legal costs should be included in the rule.

“It is unconstitutional to add legal costs because if the interest has mounted up to match the outstanding capital amount, usually because the consumer has not paid, the credit provider is prevented from collecting what is owed to them,” he said.

Second, there isn’t clarity on how the in duplum rule should be interpreted. While the NCR had issued a white paper on their own interpretation, Jonker described it as “totally impractical”, and noted it had been referred to Credit Industry Forum to work on a practical interpretation and circulate it. Even so, it would act as a guideline and not as law, he said.

So once facing debt collection through litigation and mounting legal fees, how do consumers get out of debt?

“That’s the problem,” said Van Rensburg. “They don’t really get out.”

Bad books

The law society has also been concerned by a practice by some law firms who buy bad books for the purpose of collection, essentially creating their own business.

“Debt is an asset, and in law there is nothing stopping an attorney from buying it. It is frowned upon, but from the legal opinions we got from council there is no legal reason they can’t do it. So we sit with the problem,” Van Rensburg said.

The director of Flemix, Alanza Flemix-Jordaan said her firm did not buy debt books and only collected bad debt on behalf of clients.

As stated in the judgment, debt collection agents working for Flemix, would, through questionable means, get debtors to sign documents that allowed for emolument attachment orders to be obtained in different jurisdictions. In his judgment, Desai said these agents are paid on completion of signature, and are therefore not independent parties, as was argued. They are, however, independent in that they do not fall under law society or debt collection council, said Van Rensburg.

In an opinion piece published in Business Day this week, Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development John Jeffery suggested legislation could be changed to force debt collecting attorneys to register with the Council for Debt Collectors to protect debtors from dishonest or unethical actions.

But Cornelius said attorneys had resisted being registered with the council because they did not want to be subject to capped fees outlined in the Debt Collectors Act.

The human rights view

Advocate Mohamed Ameermia, the commissioner of the South African Human Rights Commission, said it would approach the government to urgently close all legislative loopholes in the Magistrate’s Court Act, and to act on the immediate needs for judicial oversight as well as to strictly cap and regulate the interest rates on loans advanced to the poor and vulnerable.

The commission joined the Western Cape case as a friend of the court.

Ameermia said South Africa’s unsecured lending market was valued at R41-billion in 2007, but had grown to R159-billion in 2012.

“All this was done in a space where the poor and vulnerable had no access to justice, and whose dignity was compromised and totally disregarded,” he said.

“Of equal cause for concern to the commission was the questionable business practices of the micro-lending industry in effecting loans to the vulnerable and the poor under such circumstances, such as engaging in questionable business practices, in abusing the legal system, to overreach the poor and vulnerable, who have either no access to legal representation and/or to court.”

Jan van Rensburg, the president of the Law Society of the Northern Province, said discussions about the issues raised in the judgment had been ongoing for some time and, although progress had been slow, already there was a draft amendment Bill pertaining to the Magistrate’s Court Act that addressed most of the issues raised.

He said the constitutional issue was that there needed to be oversight by magistrates instead of rubber-stamping by clerks of the court.

Hennie Ferreira, the chief executive of MicroFinance South Africa, said: “For the credit world to work, debt collection must also work fairly. And a big part of the issue is that the department of justice, national treasury, the department of trade and industry, the national credit regulator, the Financial Services Board, law societies and credit societies need to harmonise their efforts. There are too many silos across various parts of the chain.”

Flemix responds

Applicants have taken the matter to the Constitutional Court, a moves required when legislation needs to be changed, but Flemix & Associates and respondents have taken the high court judgment on appeal.

Alanza Flemix-Jordaan, Flemix’s principal, says Flemix and 13 of the respondents respectfully believe the judgment is wrong and they are confident it will be overturned by a higher court.

Should the judgment be upheld, it will effectively end the process of the granting of emolument attachment orders by consent.

“Debtors will be forced to appear in court and, apart from the additional costs for debtors, our courts also do not have the capacity to deal with this,” Flemix-Jordaan says. She notes that the only other alternative for legal collections will then to be in warrants of execution against the movable property of debtors – “an inhumane and very expensive process for debtors”, she said.

“The result of this will have a devastating effect on the unsecured lending industry as creditors will not extend credit if there is not an efficient way to collect bad debts, resulting in poor people effectively being denied the right to credit.”

Although Flemix and its clients argue the judgment is wrong, Flemix-Jordaan says the firm hasn’t used Section 45 for consent to foreign jurisdictions since 2014; “should the Constitutional Court agree with [Judge Siraj] Desai’s interpretation of the relevant legislation, it will have no effect on our current business model”.

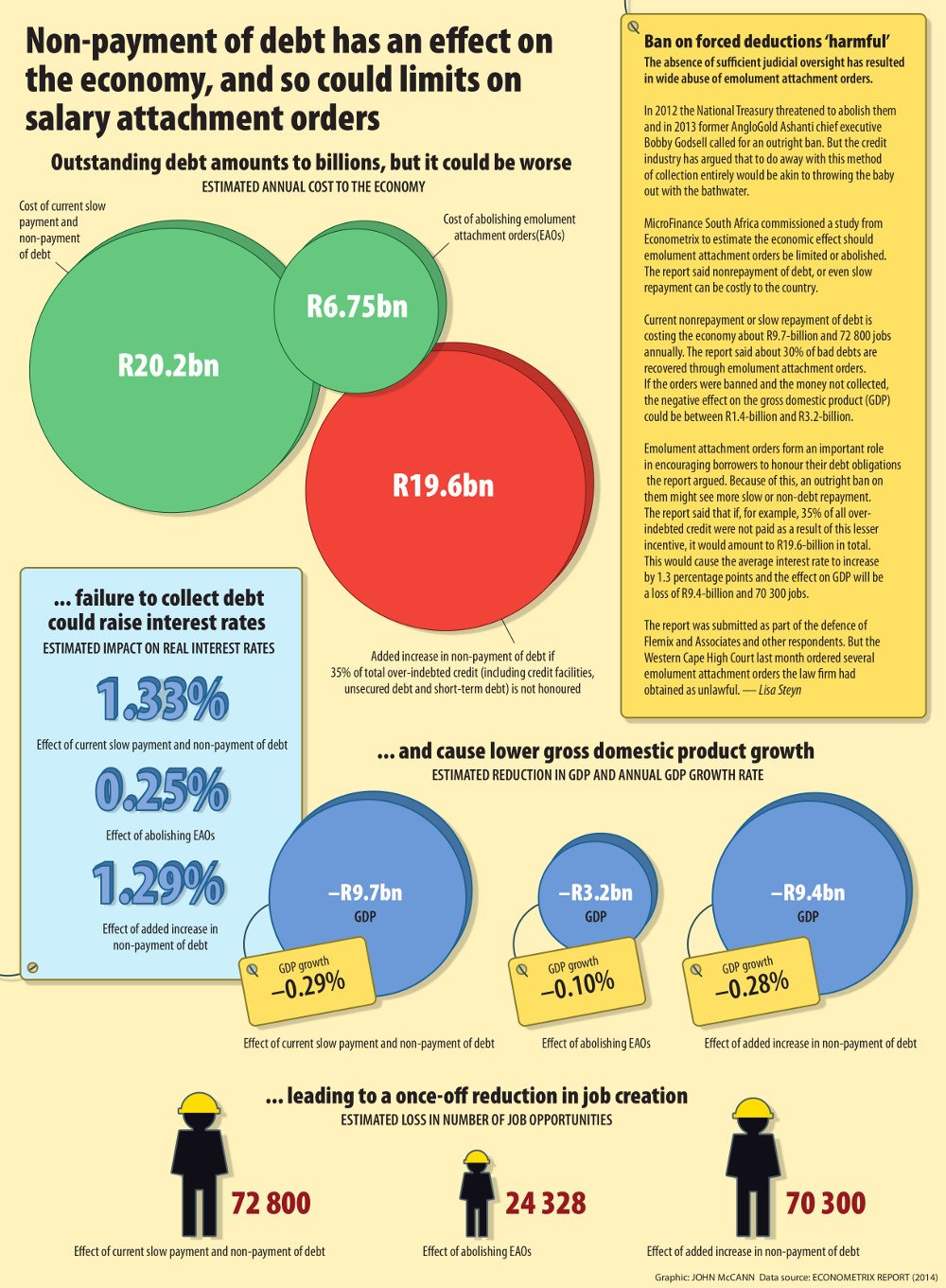

But Hennie Ferreira, chief executive of MicroFinance South Africa, says there are two discussions about what happens if and when the law changes.

“If you, as a consumer, don’t service your debt, the worst that can happen to you is some form of legal collection. You don’t go to jail. The punishment is just that you have to pay. If this mechanism [the emolument attachment order] becomes inaccessible to the industry, the consumer loses the threat to have to pay back.”

This, Ferreira says, raises the risk for lenders who will, in turn, become selective about who they lend to.

South Africa does not cap deductions

There is no statutory limit on the amount that can be deducted from the earnings of a debtor, or the number of orders that can be granted against a debtor.

In the case of an applicant brought to the high court in Cape Town by Stellenbosch University’s Legal Aid Clinic, this meant that when a clerk of the court issued three attachment orders on the same day, it attached almost her entire salary. Orders, the judgment found, had been issued without assessing whether the applicant could afford the deductions.

South Africa may have no cap on how much can be attached from a debtor’s income, but other countries have instituted regulation in this regard.

Judge Siraj Desai’s judgment on the case notes that limits have been imposed in a numbers of countries including the United States, Germany, Australia, England, Wales and Rwanda.

US law allows no more than 25% of a debtor’s after-income tax be attached per week.

In Australia, the debtor must be left with $447.70 or more after earnings are attached.

In Rwanda, only a third of a debtor’s salary can be attached.

In Germany, a limit to what can be attached is imposed according to income bands, and the number of dependents the debtor has. A higher proportion of income is attached when individuals earn more, said Desai.

Additionally, some forms of income, such as annual bonuses and certain security payments, cannot be attached. Other special circumstances, such as disability, are taken into account.

In England and Wales, the law prescribes a protected earning rate – the amount of money the debtor requires to support themselves and their family and includes expenses such as food, rent, mortgage, electricity and gas.

Judge accuses creditors of ‘forum shopping’

The judgment, handed down by the high court in Cape Town last month, said debt collection used by micro-lenders gave rise to “significant disquiet” that creditors had driven the process of obtaining the emolument attachment orders with no judicial oversight.

A central issue was obtaining attachment orders from courts far from where the debtors lived and worked.

This compromised their ability to access the courts.

Judge Siraj Desai accused Flemix & Associates of “forum shopping”, a practice by litigants to have their legal cases heard in the court thought most likely to provide favourable judgment.

Pivotal to Flemix’s debt collection procedure was to have the debtors’ written consent to judgment, to pay debt instalments, to have an emolument attachment order issued against him or her and to consent that the court’s jurisdiction be located far from their home. The judgment found the consents obtained were not given either voluntarily or on an informed basis.

Desai ordered the emolument attachment orders against the applicants be declared unlawful and invalid.

He further declared a clause where a debtor consents to judgment in the Magistrates’ Court Act inconsistent with the Constitution, as it fails to provide judicial oversight.

He also ordered that the loophole used for forum shopping, section 45 of the Magistrates’ Court Act, no longer permits a debtor to consent to the jurisdiction of a magistrate’s court other than that where they live or work.