Municipalities don't have access to the necessary expertise to ensure that water is clean and efforts to improve the situation are ignored.

NEWS ANALYSIS

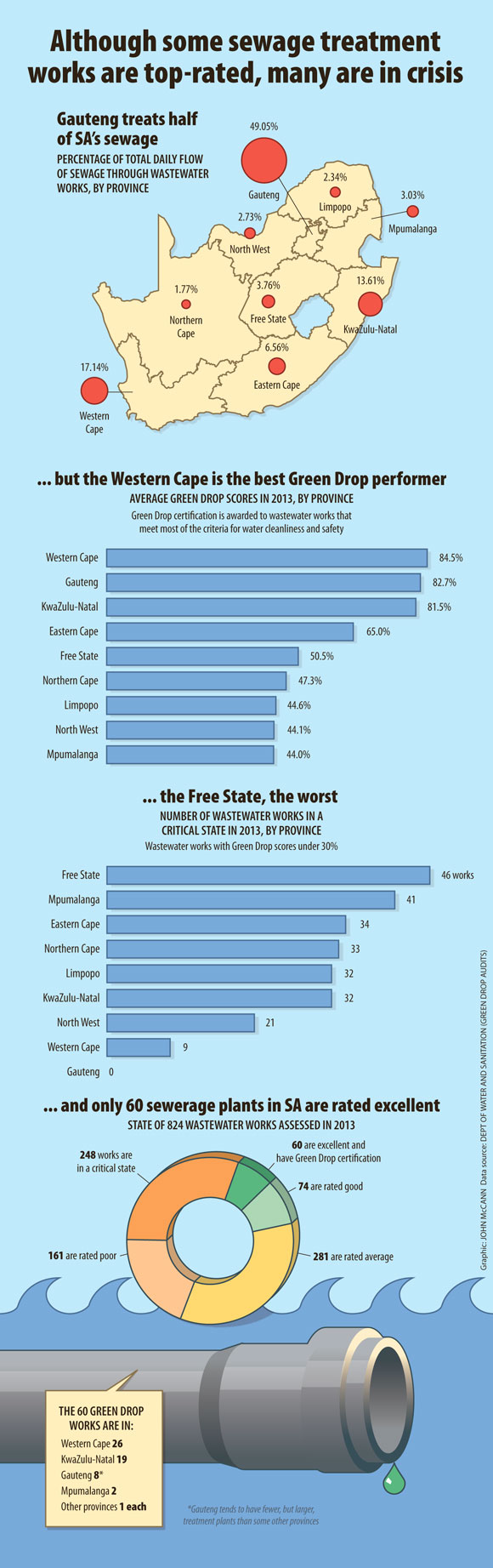

Four billion litres of polluted water are released into South Africa’s rivers everyday. This makes people sick and, in extreme cases, kills them. The water should be clean but a third of all sewerage plants were officially classified as “in crisis” in 2013. Rather than releasing current information the departments have kept back data on water quality and the capability of sewerage plants.

This data should come out every year, through the water and sanitation department’s Green Drop report. Started nearly a decade ago, it scores each sewerage plant.

Those that do their job properly – in releasing clean water – and attain more than 90%, get a Green Drop award. In 2013 only 60 received this, while 248 were listed “systems in crisis”.

When it first started the awards, the department said many of the plants “had become a prime risk to human health and a safe environment”.

The extreme version of this risk was evident when babies in Bloemhof, North West, died in June 2014 because they had consumed polluted water. In 2010, half of the field in the Dusi Canoe Marathon came down with diarrhoea from the dirty river water. But with water services reaching only two-thirds of the population, rivers and dams are a critical source of water.

Difficult to quantify

Further health effects are difficult to quantify. A special edition of the South African Medical Journal from 2009 said 85% of the country’s sewerage infrastructure was “dilapidated”. This would lead to an “epidemiological nightmare”. The country already has one of the highest under-five mortality rates for similar developing countries in the world; 10% of these are attributed to diarrhoea, it said. Even this was a minimal estimate of the effect of sewage – the immune system of people with HIV is particularly vulnerable to water with high E. coli and coliform counts.

The last two Green Drop reports have not been released, and the 2013 findings were released as a summary in January this year.

In the past two years, the Mail & Guardian has talked to a dozen people in the water sector who all pointed to the Green Drop being shelved because of the damage it posed to municipalities. A water official in Polokwane said there was fear the data would be used to lay criminal charges against the government.

“What you are essentially doing is giving people an in-depth list of your failings and basically asking them to link these to deaths,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity. By not releasing the data, the government ensured people had little chance of knowing what was polluting their water. “You would be crazy as government to hand over something so damning,” said the official.

A retired municipal water and sanitation official in KwaZulu-Natal told the M&G this year: “Our sector leader [water and sanitation department] is largely ineffectual when it comes to regulation and support.”

‘No follow-through’

Because sewerage plants fell under the co-operative governance department, water affairs cannot directly intervene to improve plants. Instead, the department had to be subtle and do things such as the Green Drop to show there were problems and encourage change at municipal level, said the retired official.

“Sure, you can issue directives and strongly worded letters, but at the end of the day, there is no follow-through because one ministry cannot criticise another.”

In 2013 the South African Human Rights Commission investigated the water and sewage crisis and found serious faults at the municipal level.

“Officials were accused of corruption as tenders were often awarded to family members or friends who are unable to complete the job promptly and adequately,” the commission said.

Other reports – by groups such as Rand Water – have found this leads to an almost complete lack of maintenance of sewerage plants. The plants are therefore unable to handle the sewage coming in, and release practically untreated waste into local water sources.

In its report on a visit to the Standerton plant in Mpumalanga, Rand Water said: “The effluent was, in essence, raw sewage.”

Well-documented woes

With the co-operative governance department’s woes well documented, the water department has consistently maintained the Green Drop is an alternative way to effect change. The 2015 summary for the 2013 findings said the failing plants had been given “purple drop” status. This would serve as a “trigger to exert regulatory and enforcement measures”.

But these measures seem to be ignored. Mary Galvin, an associate professor in the department of anthropology and development studies at the University of Johannesburg, says municipalities normally ignore directives and any incentives to improve their treatment works.

There are no consequences for polluting water, he says. Attempts by water affairs to change this were continually blocked by political considerations, especially when criticism of municipalities would be seen as potentially costing votes, he says.

“We need a situation where local officials know that if they do not do their job, another organisation will take over and they will lose their patronage benefits,” said Galvin.

Locals no longer use water from the Klip River, but cattle still drink the polluted water. (Gustav Butlex, M&G)

The water and sanitation department was unable to respond to questions in time. But in response to the M&G questions on enforcement last week, its spokesperson Sputnik Ratau said, “All forms of pollution are a concern for the department and government generally.” Everyone who has a water license had to comply with the law, he said. But when people did not, his department uses a stick and carrot approach. “Enforcement needs to be understood as a way of also assisting those who pollute, or engage in illegal activities, to know their responsibilities.”