Familial bonds are not preset at birth

Lesley and John Brown had been trying to conceive for nine years. The failures took their toll: Lesley became depressed, and at one point suggested that John find a “normal woman”.

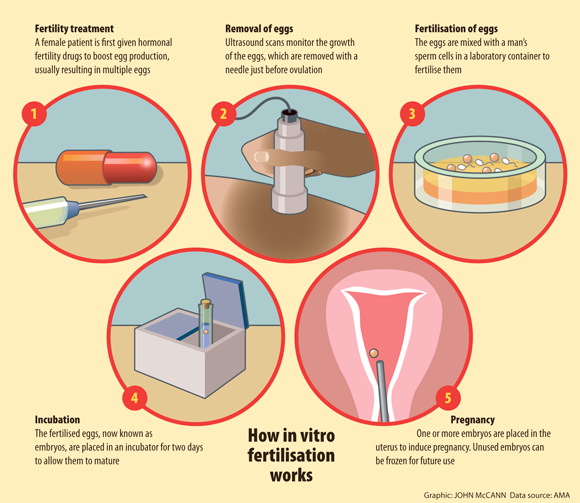

Eventually, she was referred to Patrick Steptoe, a gynaecologist at Oldham General Hospital in Greater Manchester, Britain. He offered Lesley an experimental treatment he had been working on with his colleague Robert Edwards. The procedure would use a long, slender probe to pluck an egg from one of Lesley’s ovaries, before mixing it with some of John’s sperm and nurturing the developing embryo outside of her body. The embryo would be placed into Lesley’s womb, where hopefully it would continue to develop. At the time, the technique had never resulted in the birth of a live baby.

Nine months later, at 11.47pm on July 25 1978, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed baby girl was born, weighing 2.6kg. Louise Joy Brown – the world’s first test-tube baby, born with assisted reproductive technology.

“Superbabe” and the “lovely Louise”, read the headlines. Public reaction was generally positive – a Gallup survey of Americans had 53% of those polled saying they’d be willing to undergo in vitro fertilisation (IVF) if they were unable to conceive naturally.

Acceptance was not unanimous.

“The fact that science now has the ability to alter this does not mean that, morally speaking, it has the right to do so,” said US general secretary of Catholic Bishops Reverend Thomas C Kelly in a Washington Post article. People had concerns. The technology was, some felt, unnatural. What kinds of families would it produce? Would the children be okay?

Today, the days of the nuclear family – a man, a wife, 2.4 children – seem increasingly numbered. Divorce is common. Gay and lesbian parents can adopt, or conceive children of their own thanks to egg donation and surrogacy. And new types of family continue to arise: single mothers by choice, who decide from the outset to have a baby without a visible father; Methuselah mothers having babies in their 60s. They raise fresh questions about the relationship of parent to child, the relative contributions of mothers and fathers to a child’s development, and what it means to be a family.

Same-sex parents

In 1976, the feminist magazine Spare Rib carried an article on lesbian women fighting for custody of their children after divorcing their husbands. Invariably, the women lost. If these children lived with two mothers, the argument went, they would be psychologically traumatised, ostracised by their peers – even “turned homosexual”.

Susan Golombok happened upon the article by accident. “All kinds of things were being said in court about the terrible things that would befall these children, yet nobody had ever spoken to the children, or done any systematic research,” she says. At the end of the piece was a plea for someone to conduct an objective study of the development of children in lesbian families. Golombok, a developmental psychology student, was looking for a master’s dissertation. She’d found it.

She dialled the Cambridge number of Action for Lesbian Parents, who’d written the article. They introduced her to some of their members and Golombok’s study began. Thirty-nine years later, she’s still going. The late 1960s and early 1970s had been a productive time for child psychology. One of the leading theorists was John Bowlby, who, largely based on children who lost their parents in World War II, developed the idea that a child’s future wellbeing hinged on the relationship with their mother in the first few years of life.

Children shown attention and affection by their mothers will grow up to view themselves as lovable, he said. Those whose mothers are uninterested, or erratic in their displays of affection, may view themselves as unworthy of love, and this could have lifelong implications for their ability to relate to others and slot comfortably into society. “Old-fashioned ideas about attachment were that children very much had a primary attachment figure and that person was the mother,” says Golombok, now professor of family research at the University of Cambridge.

Nurture vs nature

Bowlby’s theories about attachment still hold sway. This line of thinking, plus the fact that childcare was almost exclusively carried out by women, meant that, when marriages broke down, custody would almost always be awarded to the woman – unless she was a lesbian.

There was also the notion that nurture held sway over nature. The world was viewed in blue and pink. Feminists striving for greater equality encouraged girls to shun pink dolls in favour of trucks, and boys were encouraged to pick the dolls up instead. Besides the fear that lesbians would turn their children gay, there was also a worry that their sons and daughters would be feminised because they lacked a father figure.

Golombok resolved to get to the bottom of these issues. Using questionnaires developed at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, she recorded and quantified not only what the families told her, but also their facial expressions and tone of voice. She also observed and scored how the members of these families interacted with one another.

She compared children raised in lesbian households with those in families headed by a single heterosexual mother. Her finding: no difference.

“People had thought the boys would be very feminine and the girls very masculine, but that absolutely wasn’t the case,” says Golombok. Children in lesbian families were no more likely to be confused about their gender identity than children in heterosexual families, and they were behaviourally and emotionally just as well developed. “Today people think, well actually, whatever parents do, it doesn’t make that much difference,” she says.

Across the Atlantic, at the University of Oregon, another group was discovering that when mothers tried to discourage boys from being boyish and girls from being girlish, it had little effect on the children.

“There’s now a massive literature about lesbian parents, and to a smaller extent gay parents,” says Ellen Perrin of Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, co-author of a 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics report on outcomes for children of lesbian and gay parents. “What they reveal is that in terms of adjustment, the children of parents who are the same sex do just as well as any other children with any other kind of parents.”

Research questioned

Not everyone is as accepting. Christian lobbying groups, such as the Washington-based Family Research Council, raise concerns about the bulk of research, including methodological weaknesses, inadequate sample sizes and a lack of random sampling. They have weighed in with research of their own, which they say proves that having gay or lesbian parents is harmful to children.

Funded with $800 000 from the Witherspoon Institute and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the New Family Structures Study, published in 2012, provided the large, random, population-based study that critics argued was missing from the scientific literature.

The study took a random group of about 3 000 young adults from different types of families and compared them on 40 social and emotional criteria. It found significant differences between children who grew up in stable heterosexual families and those whose mothers or fathers reported having same-sex relationships. They “look markedly different on numerous outcomes, including many that are obviously suboptimal (such as education, depression, employment status, or marijuana use),” wrote the study’s author, Mark Regnerus, a sociologist at the University of Austin in Texas. “Although the findings … may be explicable in part by a variety of forces uniquely problematic for child development in lesbian and gay families – including a lack of social support for parents, stress exposure resulting from persistent stigma, and modest or absent legal security for their parental and romantic relationship statuses – the empirical claim that no notable differences exist must go.”

Outrage

Regnerus’s study provoked outrage. Its methodology, and the peer-review process of the Social Science Research journal it was published in, came under heavy fire. “Among the flaws … he never actually defined children who were living with same-sex parents; he only asked whether there had been a same-sex relationship at some point in the child’s first 18 years,” says Perrin.

In other words, Regnerus wasn’t comparing like with like: few of the children he studied had come from stable households headed by lesbian or gay parents, yet he was comparing them with children raised in stable heterosexual marriages. The majority of those parents labelled “gay” had seen their relationship with the child’s other parent deteriorate, and although plenty of children with divorced parents do just fine, marriage breakdown is a known risk factor for child adjustment problems.

Paul Amato of Pennsylvania State University was among those who peer-reviewed the study, though he also acted as a consultant during its design. He says it’s reasonable to conclude that the elevated problems seen in these young adults were a result of family instability rather than the sexual orientation of their parents. If anything, Amato believes the research bolsters the case for same-sex marriage: “The lesson is that children thrive on family stability, including children with gay and lesbian parents,” he says.

It would be easy to dismiss the New Family Structures Study, except that it continues to be cited approvingly by campaigners for “traditional” families. The study has also been cited by Russian politicians as a reason for denying gay and lesbian parents custody of their children. Golombok says her own studies aren’t perfect: “A lot of the studies have small sample sizes.” However, she points to several meta-analyses that have pulled together the results of multiple small studies over 35 years of research – and they still suggest that parents’ sexuality makes little difference to children. There are some differences, of course. Children raised in lesbian or gay households are more likely to have experimented with a member of the same sex, possibly because they feel less stigma attached. And although there is no difference in their mental and emotional stability, children with lesbian or gay parents are slightly more likely to report having been bullied.

Reaction of others

Kate* lives in Scotland with her partner, Rose*, and her biological daughter, Anna*. She had always suspected herself to be gay, but never experimented with her sexuality until she divorced. When she met Rose it was love at first sight, she says. She wasn’t particularly worried about Anna’s reaction, but was concerned about her school friends.

Anna, aged nine, says she has experienced some teasing. “A boy in my class said that my mums were gay,” she tells me. “He didn’t really mean it in a nice way, so I didn’t like that. I’ve had a few other people calling it weird, but that’s all.”

On the whole, she says she likes having two mothers – three, if you count her father’s new partner.

Anna’s experiences echo a report by Stonewall, the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights charity, and the Centre for Family Research at the University of Cambridge, headed by Golombok. Children with gay or lesbian parents say they have to answer a lot of questions about their family – which can make them feel unusual – but on the whole they don’t really think about how their family compares with others. They do dislike the common use of the word “gay” as a playground insult, and they say that teachers don’t respond to its use in the same way they would to racist language. And some children report positive responses. “When I went to high school I thought it might be a bit awkward if someone came round to the house,” says Morag (18). “They’d ask ‘Where’s your dad?’ I would say ‘I’ve got two mums’, and they’d say ‘Coo-ool’.”

Anna thinks schools should do more to teach pupils about different types of families: “Some people might think it’s kind of weird, but if they knew what it was like, they wouldn’t think it was weird … it’s just … instead of having a dad, you live with another lady.”

Full-time fatherhood

Chris Youlden and Harry Ispoglou may be the epitome of a 21st-century family: two gay men who, against the odds, succeeded in producing twin boys – Kal and Loukas – through egg donation and surrogacy.

There were no traditional parental roles for Chris and Harry to fall into. Instead, they had to invent their own. Harry is the boys’ biological father. He took the first seven months off work to care for them. Now he works full-time and Chris provides the majority of their care. They say having twins has helped to level the playing field. For instance, mothers often find themselves shouldering the bulk of sleepless nights because of breastfeeding, but Harry and Chris experimented with different approaches. “It started out with one of us [feeding] while the other had three hours’ sleep,” Chris recalls. “Then we tried sleeping in different beds. In the end we just shared it because both of them wanted to be fed at the same time.”

What happens when fathers assume the role of mothers? It is a critical question, says Ruth Feldman at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, not just because of gay fathers, but because of single parents, adoptive parents, foster parents and other people raising children without the experience of pregnancy ?and childbirth.

In Bowlby’s time, men were considered secondary to child development; their role was as breadwinners, not caregivers. Women were believed to be innately maternal. Exhausted mothers often say that maternal instinct kicks in and that this helps get them through those early months. Brain scans have revealed a kind of caregiving network in the brain that fires up when women are exposed to the hormones of pregnancy and birth. Women become more attuned to their infants’ cues and more vigilant for their safety, and they are also wired to get an emotional kick out of interacting with their children.

So, what of those who are not boosted by pregnancy hormones?

Feldman is one of the few researchers to have investigated the paternal brain. She and her colleagues compared the brains of mothers acting as primary caregivers, fathers acting as secondary caregivers, and gay men raising children.

They found that “there is this kind of parental caregiving network [in the brain] that is activated in adults who are involved with infant care”, she says. This involves brain structures linked to vigilance, reward and motivation, plus other circuits implicated in social understanding and empathy. They found that, in women, emotion-processing areas such as the amygdala were more active than in their less-involved male partners. The enhanced vigilance this brain activation affords is critical for infant survival, says Feldman.

But men showed greater brain activity in a different area, the superior temporal sulcus, which is associated with reading the intentions of others. Gay fathers showed activation of both areas, and enhanced connectivity between them.

Primary caregiver

Past research has suggested that fathers generally tend to engage in more boisterous, stimulating and unpredictable interactions with their children, whereas mothers play a calmer, more soothing role. Yet several studies have found that this changes when they are given different responsibilities – if the father takes on a greater proportion of the childcare, for instance.

Usually, a mother is more likely to be up at night, watching over the baby, while the father sleeps. But when there is no mother, the father assumes this role.

Feldman suggests the way they do it is through the connection between the superior temporal sulcus and the amygdala. Her group also found a greater degree of overlap between these brain structures the more time any father spends alone with the child, with sole responsibility for its safety.

To Feldman, the message is clear: if you become a primary caregiver, your brain will adapt and provide for your child’s needs, no matter what your sex.

What children need is at least one person who is dedicated and devoted to promoting their wellbeing, says Michael Lamb, professor of psychology at the University of Cambridge. His research has shown that, contrary to Bowlby’s theory, babies and children can form multiple attachments to people who are consistently involved in their lives.

Stability

Children thrive on stability, and are harmed by conflict or the loss of contact with one of their main caregivers. “Do you have a parent who is sensitive and attends to the needs of the individual child? Does that parent have the financial and socioemotional support that allows them to function while not being overwhelmed by stress?” says Lamb. “That is more important to a child’s development and outcomes than whether they have a male or female role model in their lives.”

“German woman aged 65 gives birth to quadruplets after IVF treatment,” announced the Guardian on May 23 2015. Elsewhere, artificial sperm are being generated from skin cells, which some day might enable infertile men to father biologically related children. Then there are co-parents, people who meet over the internet with the sole purpose of raising a child in a platonic relationship. “I am constantly surprised by all the different ways in which people can create families,” says Golombok.

The first baby conceived using a donor egg was born in 1984, and the use of sperm collected and frozen in sperm banks has only become more popular. More than five million babies are estimated to have been born using IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies since 1978.

Golombok was one of the first to study the relationships between parents’ use of assisted reproductive technologies and the psychological development and wellbeing of their children. “People thought that IVF children might be very over-protected,” she says, “or that parents might be more distant because their baby had been conceived in a lab.”

These fears, like others about new parenting structures, have proven misplaced. Such technologies have been a giant leap for hopeful parents. They were expected to aid the growth of families. Instead, they have helped families evolve, challenging our traditional ideas of what a family is. Nearly 40 years of research has shown Golombok that, though the cast may change, the core values remain: artificially conceived children do fine; the absence of a father or a mother doesn’t spell disaster for the children; the children of gay and lesbian parents do no worse than those from more traditional families.

“I think that just wanting to have children – it sounds very trite but I think it actually explains a lot of our findings,” says Golombok. Many of those she has studied are gay adoptive parents: men who were closely screened before being entrusted with children. “In these new families, the parents can’t have children by accident,” she says. “They have overcome lots of hurdles … so these are really committed parents with very wanted children.”

- Some names have been changed to protect the identity of those concerned. This story first appeared on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence. The link to the original story is: http//mosaicscience.com/story/exploding-nuclear-family