Universities have failed to implement the knowledge project and transform

The works of Alinka Eche-verria cover the walls and floor of the Johannesburg Art Gallery – large-scale prints, decoratively scattered rock and glittering bones of once powerful mammals.

Whether you chat to the artist or view her ambitious work, it is evident she is an individual preoccupied with the conflict between physical and psychological freedom. Echeverria blends physical representations of the real world and esoteric concepts, such as faith, which penetrate the objective world.

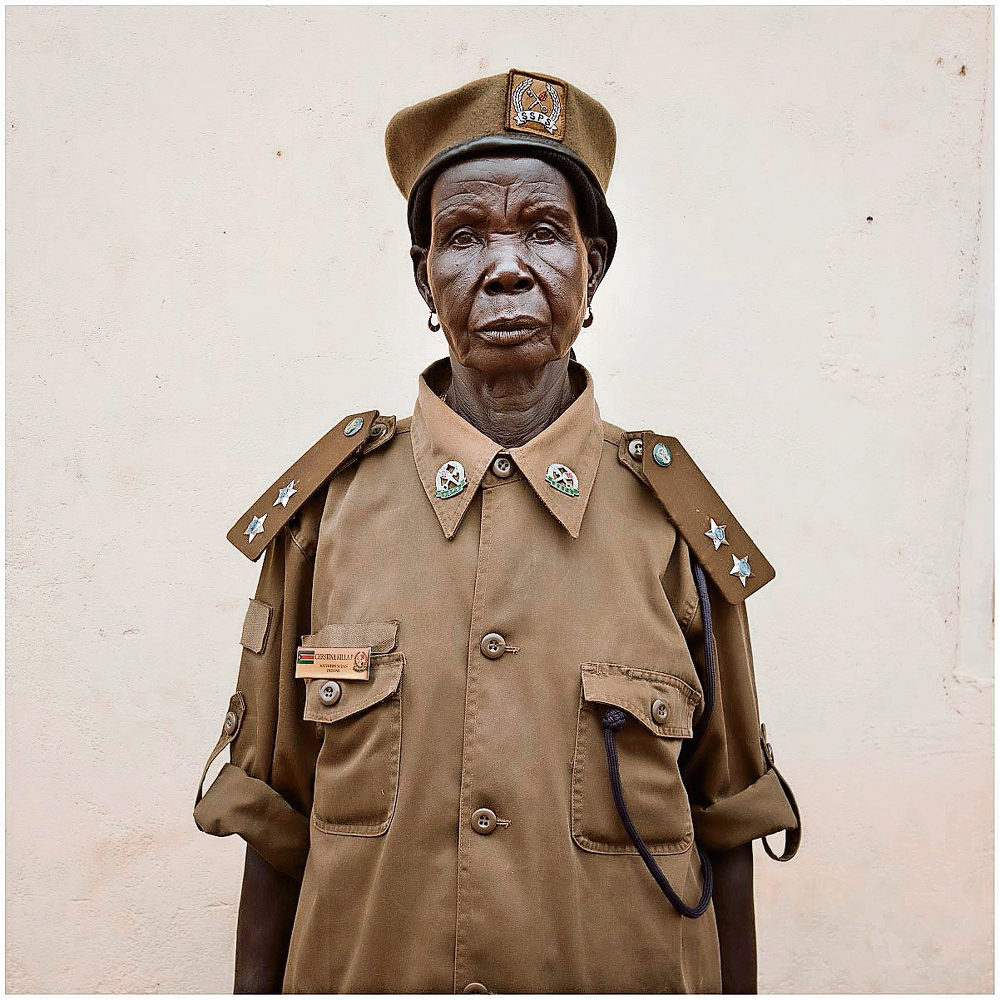

The stern gazes in her acclaimed photographic series Becoming South Sudan depict with joy the liberation achieved in South Sudan in 2011. But the elation documented also hints at the impending struggles independence places on any newly liberated nation. The artist captures the fixed stares of the South Sudanese people in the solitary and limited framework of a photograph, and in doing so succeeds in finding the monumental in the minimal spaces her camera affords her.

Mexican-born, she spent much formative time in the Americas and Africa. These seminal travels followed her master’s degree in social anthropology and development at the University of Edinburgh in 2004, and studies at the International Centre of Photography in 2008. Echeverria’s ethnic roots remain the foundation for her exploration of liberty and self-determination, themes that permeate her work.

A photograph from the series ‘Becoming South Sudan’

In the series Road to Tepeyac, she investigates independence or dependence through religion and faith. The series comprises 300 images of pilgrims travelling to the Basilica de Guadalupe in Mexico, with their own representations of the Virgin of Guadalupe on their backs. Although it is an ambitious work, the series reduces itself to a minute screenshot of the celebration, emphasising the scale of the pilgrimage, made by six million pilgrims each year.

Road to Tepeyac hangs in the gallery in four columns placed in a simple order, but it is a grandiose statement and depiction of the themes of devotion. Although it questions the place of religious faith in the modern world, it shows the importance religion holds for each subject in the 300 photographs.

“The series explores the relationship between an invisible presence and its materialised expression,” says Echeverria. “The iconographic depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe, I would argue, is an amalgamation of the Catholic Virgin Mary and the Aztec goddess Tonantzin … and it is important to remember that each version of the Virgin is as important as the next because it belongs to that person.”

Echeverria is an artist seeking the higher meanings behind the smallest phrases, concepts, celebrations and contexts. She says that her work is built around the foreign context in which she immerses herself: “My images choose me. I go from the world to the page, not the other way round. I do not sit around at home, compose them and think about them. You cannot.”

An image from ‘Road to Tepeyac’

She is an individual who has accepted her place, not only as an artist but as a person in a world of larger discussions. As she stressed at the opening of her solo show: “I insert myself into a context with a very general interest and try to experience what I’m photographing.”

Once she had inserted herself into the context of the pilgrimage, she felt a duty to document the celebration in the most truthful way.

This method remains a staple of all her work on show here. It is the acceptance of the role of the outsider. Echeverria looks at the landscape and its contents with childlike wonder and attempts to extract the symbols and signs from the figures she photographs. And, with an even hand, she looks for how faith, liberty, prosperity and devotion influence the physical world.

An image from ‘Road to Tepeyac’

When Echeverria’s exhibition 1:1 opened, critic Sean O’Toole and artist and academic Raimi Gbadamosi were part of a panel discussion entitled Duty of Looking. O’Toole commended Echeverria’s work, describing Becoming South Sudan as good reportage and Road to Tepeyac as the perfect public introduction to her as an artist. O’Toole also focused on the duty of looking that everyone holds.

Echeverria’s way of extracting information from a harsh landscape or a beautiful face upholds this duty she has taken on with such conviction and commitment.

1:1 is at the Johannesburg Art Gallery until October 25