The first time I saw “Mac” McKenzie he was playing an electric bass with one hand in a band that was going at 100 miles an hour. The setting was Rustler’s Valley: his group, The Genuines, was setting a small, muddy tent of midnight revellers on fire through some pushed-to-the-max monitor speakers, purloined from the rained-out main stage. I was gobsmacked.

Time passed. I didn’t see McKenzie again for 20 years or so, then suddenly, almost every time I went out I bumped into him. That’s because he’s busy putting together the Mac McKenzie Songbook Orchestra in Johannesburg; he also plays with the Friendship Orchestra in Basel, Switzerland, and the eponymous Cape Town Goema Orchestra.

Directing orchestras is perhaps the logical progression for a musician born in the 1950s who always wrote his own songs. On the rock and jazz circuit since the 1970s, McKenzie “reached the South African ceiling several times” with various solo and collaborative projects, and tasted some success in Europe (“we had enough girls, we had enough money, we had enough party material”).

These days, however, he’s far more serious: his mantra is writing scores, and playing with musicians who can read and follow them. “It’s really difficult to make a living from having a record deal; there is this myth that you can do so. But, when you’re not touring, you’re poor … so I learned to score my music, because people take you seriously when you write music. You can take that piece of paper with you anywhere in the world; it helps you to define your own destiny.”

McKenzie never studied music and had to teach himself how to read and write. “The stuff that was going on in my head was symphonic by nature … so I thought I had better write this music down, and only play with musicians who can read the music … and that was a hell of a journey, because I then had to give up the jazz gigs, because jazz musicians, even if they have scores, don’t bother to read the scores … So then I said, ‘that’s it’, and then I started writing, but it was full of inaccuracies, because I didn’t grow up in that environment.”

The rise and fall of The Genuines

He did, however, grow up surrounded by an organic tradition of Kaapse Klopse, music in Bridgetown (near Langa) in Cape Town. His father “Mr Mac”, whose father was also a musician, was a band leader, and McKenzie began learning chords on the guitar at age nine. “After your voice, the guitar was the most mobile instrument.” In his teens he played with a variety of so-called coloured bands where he “learned his chops”, but he became increasingly frustrated by the fact that he was the only one interested in playing music he had composed.

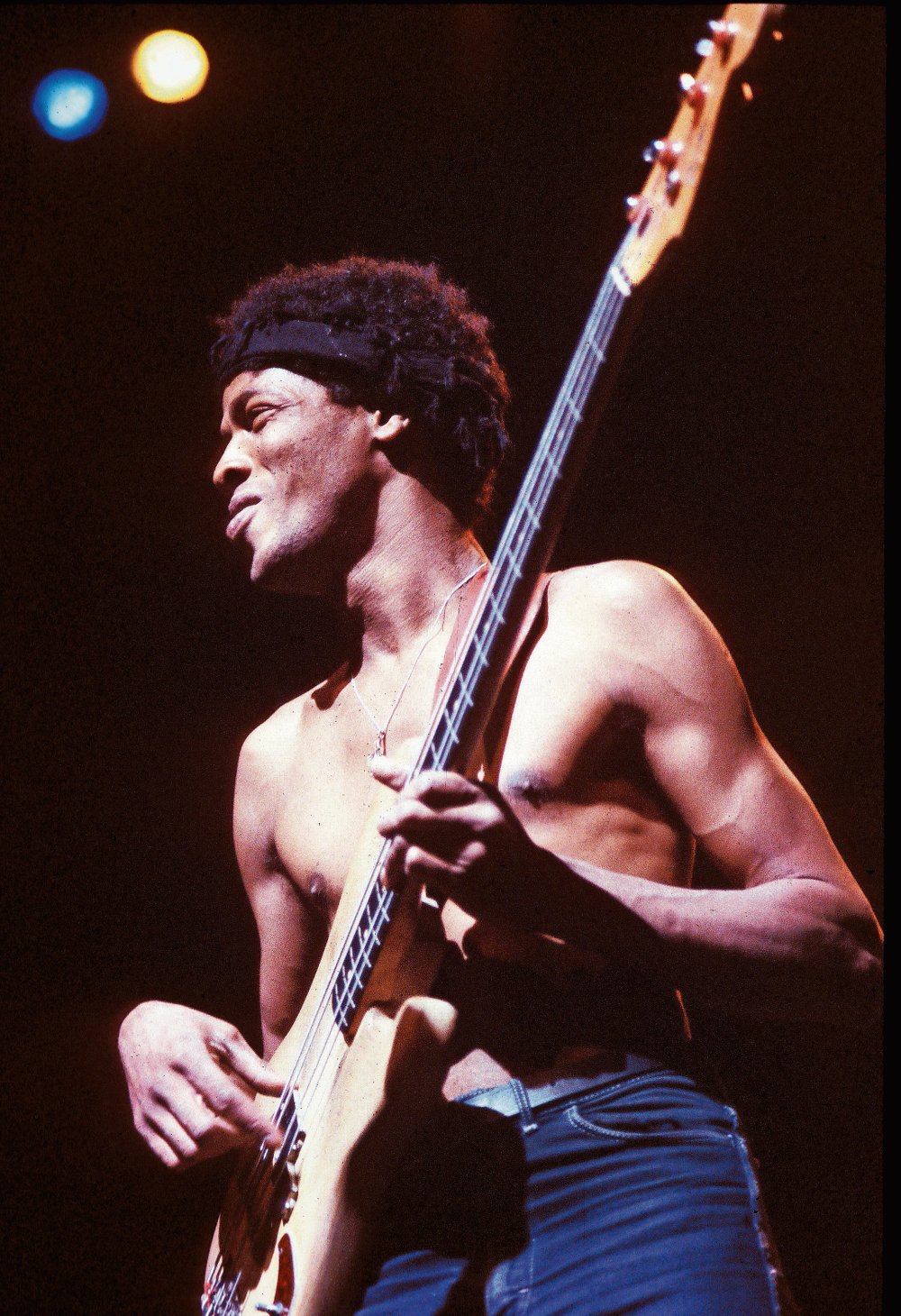

Mac McKenzie during his wild days with The Genuines.

(Paul Weinberg/africamediaonline)

“They just wanted to play cover versions, and still do, up to this day.” He found the only people interested in musicians playing original music was “the white circle”, and he began playing in white areas, despite the Group Areas Act — “all this culminated in the fame and fortune of The Genuines”. Thereafter began a series of ocean-crossing hops. The Genuines rose and sank as the band swallowed and spat out a series of drummers, before McKenzie disbanded it, embarked on solo jazz gigs in Cape Town and Europe, and, finally, settled into his present orchestral direction.

Traces of frenetic goema and jazz still emerge in his pieces, though what he is doing now defies simple categorisation. So what exactly is McKenzie writing? He modestly describes it as genre busting. “It’s frontier activity, it’s pushing boundaries, it’s establishing a new theme, and a new sound.” Pushed for a label, he said: “It’s kind of cultural, indigenous ?stuff, mixed with classical, so most people will understand if you call it crossover.”

Musician Dax Butler said of McKenzie’s latest music: “It was evocative and really moved me, drew me in, unlike a lot of jazz. It’s got parallels with Zappa — Frank also wanted to be regarded as a serious composer. “Mac cuts the mustard, he is definitely a force to be reckoned with, and it inspires me to see he is still out there doing his own stuff, when he could just be making a living from playing cocktail music.”

McKenzie’s ground-breaking work

Writer and producer Deon Maas said: “I have always seen Mac as a shape shifter in South African music. He has always taken the existing and moved it further, making it more difficult for others to reach the goalposts. Creatively, he mixes roots with new experiences, making him more cutting edge than most people realise. His new work is once again ground-breaking, taking his own compositions and especially goema to another, previously unexplored level.”

The Songbook is a collection of classically trained, young orchestra players, probably the only musicians capable of following his dense scores and unusual time signatures. Even for these pros, the music is a challenge. Drummer Greg Whit said he had never played on goema drums before he pitched for Songbook rehearsals. McKenzie’s latest piece, Finale, is a lengthy saga about the troubled history of South Africa, in 10 movements.

In his words, they are: “Unimpeded — the Khoisan are playing their music, in a simple way, in 1652, running around in the Garden of Eden with their bows;

“Impending Impact, as the Europeans start coming in, and then you hear violins;

“Mixed, where the races start mixing … the extended lyricism of 17th century Europe starts to mix with the indigenous sounds; “Church Song, where you get the religious stuff, the influence of the missionaries, the dirges of the Catholics, the Gregorian chants; “Little Party, because now the music is starting to gel, it goes into goema, then it goes into bebop swing, then back into goema;

“Militair. There is ‘mos kak’ happening in the party, fornication, so this is when the military steps in to sort things out;

“Postwar — I like to call it Lost War, because all wars are lost. After the war people have to bury bodies and patch people up, there is all this destruction. It’s a very sad piece;

“Rock Against is where people come out and start rocking in protest … that is your amandla kind of theme … that has always happened in South Africa, after the wars, the victors have had to hold down the swelling masses …

“Nine A is called Reconciliation, and nine B is Romance …

“Carnival Victory, a straight-forward goema piece …”

South Africa’s diverse roots

The piece he is developing after that, Symphony No 2, is also a narrative, tracing the movements of the Nguni tribes down from Central Africa into our country. It incorporates mbiras from Zimbabwe, maskande music from the Zulus and tablas from the Indians in KwaZulu-Natal. Once McKenzie has “settled the scores” of these works, he aims to take them, with a few principal musicians, overseas. McKenzie pays his musicians from his own pocket. The money comes from various grants and is meant to cover his rent, but he uses part of his rent money to get the best people in to do the job.

“I would rather live on the street, and have a beautiful music product, and improve chops, than live with creature comforts,” he says. He might not be leaping around the stage à la Genuines any more — and would probably look ridiculous if he did — but his imagination is pretty agile. Mac is impressive; he’s a product and creator of South Africa’s diverse roots, an expression of how twisted yet beautifully they can grow.

Watch Mac McKenzie Songbook rehearsals on Wednesday evenings at The Bohemian in Westdene. He also plays with a bigger orchestra at MusicWorX in Rosebank every three months or so.