EMPLOYMENT

The problems of South Africa are clear: high unemployment, high inequality and low growth, combined with a lack of consensus over what to do.

This may be because of disagreements over technical policy, political constraints or broader visions – or it could be that key interventions will only be effective in seven, 10 and 15 years’ time, and the political need is to deliver solutions in three, five and seven years.

It might be more fruitful to think in terms of a “grand bargain”: a package of policies that will balance opposing perspectives, whose differences cannot be resolved by technical debate, and to set the needs of short-term political-economic imperatives against the longer time period needed for policy interventions that address deep structural legacies.

Domestically, the structural challenges are well known, many being part of the legacy of apartheid:

- Large inequalities in financial, physical and human capital (education and health), especially along racial lines;

- A particular spatial pattern of residence relative to place of work, leading to high reservation wages;

- Strong organised labour in the private and the public sectors – which can resist declines in real wages – combined with a small informal sector;

- A significant export-oriented natural resource extraction sector, which requires increasing capital intensity and is vulnerable to global commodity price trends; and

- An economy relatively open to trade, investment and financial flows.

Policy dilemmas

South Africa seems to be in the following spiral: global technological trends, imported to South Africa because of its openness, are leading to the less intensive use of basic labour – that is, technology displaces unskilled labour by capital and by skilled labour.

The labour being displaced could be rehired if wages were to fall, but there is resistance from organised labour to real wage reductions, so a low real wage strategy does not seem to be available politically, at least for the three-five-seven-year period. Export demand is constrained because of competition from technically comparable producers in other countries that can rely on lower real wages. As a result there is high unemployment.

With unemployment comes the pressure to expand employment in the public sector, which, with higher wage demands, leads to a rising public-sector wage bill.

If the fiscal balance is maintained through higher taxation, or if higher fiscal deficits elicit tight monetary policy, employment in the private sector is hit again, adding to the way in which global forces contribute to rising unemployment. The spiral continues.

Many interventions have been implemented, including:

- Greater expenditure on public education, health, housing, services and transfers;

- Public employment schemes;

- Skills development and skills matching services;

- Wage subsidies to employers;

- Minimum wages;

- Support for very small-scale enterprises in the informal sector;

- Export and investment promotion for enterprises in the formal sector;

- Public investment to counter infrastructure constraints on private investment; and

- Fiscal deficit targets and monetary policy that targets inflation.

These interventions are not necessarily consistent and policy often undoes with one hand what it has just done with the other.

For example, a range of capital subsidies favours the use of capital over labour. Wage subsidies to employers counter high wages in the organised sector at the same time that a minimum wage would put a floor under wages. Public employment schemes can, at best, be a temporary device. And public expenditure depends on public revenue, which will grow sustainably only when the economy grows through greater investment.

On wages and employment, there are two major views. One is the standard labour-economics view that, if the real wage was adjusted sufficiently downwards, unemployed labour would be employed. A value of 0.7 for the conventional wage elasticity of employment is marshalled in evidence – a 10% fall in the minimum wage would lead to a 7% rise in employment.

The counterview is equally well known. Halving the unemployment rate would require a 40% decline in the real wage, which is beyond the realms of political feasibility, given the inequality between labour and capital.

Within this background, one can discuss policy focus, effectiveness and inconsistencies but I suggest we should rather focus on the following questions: What might be the grand bargain that would advance growth, employment and equity? What types of policy could fulfil this?

Lessons from Brazil

In thinking about these questions, Brazil is a country from which South Africa has much to learn.

It is not South Africa by a long shot, including having a much larger population. But it has many common structural features.

It is a middle-income country and has high levels of inequality. Economic differences based on racial origins are part of the discourse. Brazilians threw off the dictator’s yoke and have moved to social democratic government. Brazil is urbanised and formalised to a significant extent, and labour organisations are strong (the government for the past 10 years has been formed by the Workers’ Party).

Despite Brazil’s structural similarity to South Africa, the main comparison lies in a difference. In the past 15 years, Brazil has had high growth rates combined with declining inequality. Between 1998 and 2009, Brazil’s Gini coefficient declined from 0.59 to 0.54.

It has had a huge significance. “Two-thirds of the decline in extreme poverty can be attributed to the reduction in inequality. For the same reduction in extreme poverty, Brazil’s overall per capita income would have needed to grow an extra four percentage points per year,” Nora Lustig, Luis Lopez-Calva and Eduardo Ortiz-Juarez argue in The Decline in Inequality in Latin America: How Much, Since When and Why (2011).

They say the unprecedented reduction in inequality is mainly the result of three factors:

- Decreasing wage differentials by educational level and reductions in the inequality in education;

- Increasing spatial and sectoral integration of labour markets, in particular in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas; and

- Larger and better targeted non-contributory government transfers.

The role of an accelerated expansion of basic education was significant. The degree of inequality in education declined. At the same time, the skills premium – the difference between the returns to those with secondary and higher education and those without schooling or with incomplete primary schooling – also declined. The combined effect of these two factors explains almost 30% of the decline in inequality.

The strong backdrop to these changes was a policy of macroeconomic stability with firm control of fiscal deficits – an objective pursued by both the Social Democratic Party (Fernando Cardoso’s presidency) and the Workers Party (Lula da Silva’s presidency).

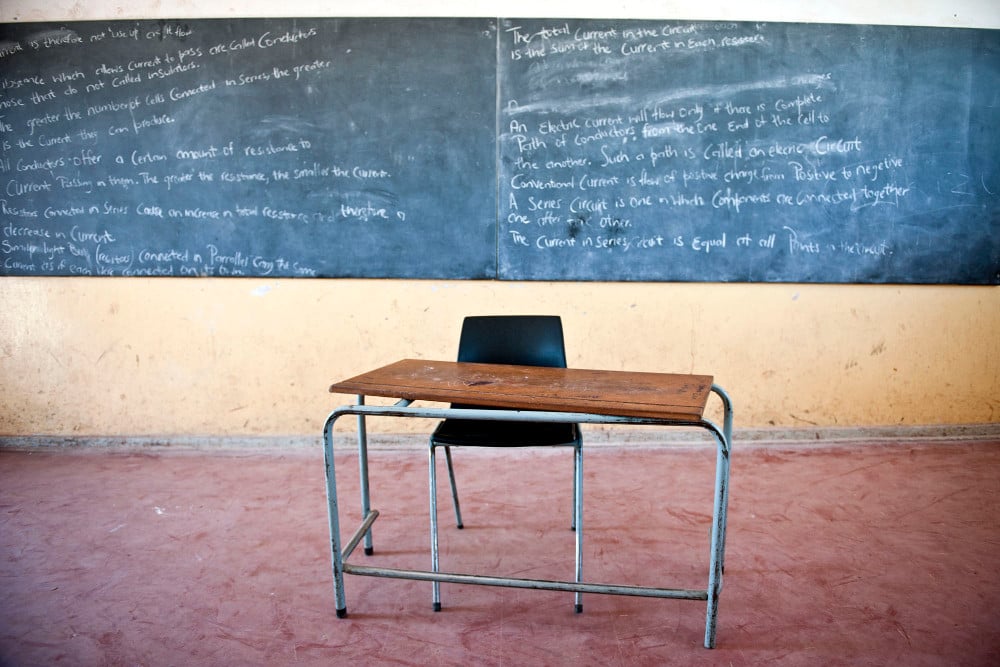

Brazil addressed, in particular, disparities in education. (Madelene Cronjé)

With this key component of an implicit grand bargain agreed upon, the other components were put in place: the expansion of basic education, minimum wages and conditional cash transfers.

It is important to note the time lags: it was a decade before the effects of the expansion of basic education were felt on inequality. The South African political imperative is to address the unemployment problem over the three-five-seven-year time period.

A grand settlement

How can unemployment in South Africa be reduced significantly in the short run without lowering the real wage and without increasing the public-sector wage bill to fiscally unsustainable levels? Here are some thoughts on possible outlines of a grand settlement:

- Fiscal rectitude will have to be a key component of the package;

- Expanding public investment in education and health as the basis of raising productivity and reducing inequality is essential. But the benefits of this will only come over a decade or more;

- In the short term, competing in the world economy on low real wages is not feasible or desirable;

- Publicly provided employment can at best be temporary. The bulk of employment will have to come from the private sector; and

- Given these constraints, the focus in the short term may have to be to reduce the nonlabour cost of private sector employment. It could provide quick gains on the employment front. A focus on this might be more amenable to consensus than one focused on reducing labour cost.

A conventional view is that the nonlabour cost of employment should account for less than 30% of total cost, therefore the effect is unlikely to be large. However, this can confuse average cost with marginal cost. Thinking of nonlabour cost in a broad sense can bring in a range of policy options such as:

- Public infrastructure improvements for enterprises in their current location;

- Infrastructure and financial inducements for enterprises to move to high unemployment locations;

- Reducing the high reservation wage induced by the high cost of transportation to work;

- Reducing monopoly and concentration on the product side to expand output and thus employment; and

- Reducing the regulatory and other constraints on small-scale informal activities.

In short: a grand bargain may have to comprise a move away from a reduced-labour-cost approach to employment policy in return for an agreement on fiscal rectitude and the nonexpansion of the public-sector wage bill.

Within the fiscal constraints, the medium-term strategy would be to build up human capital by investing in education and health, while the short-term strategy, over the crucial three-five-seven-year time horizon, would be to reduce the nonlabour cost of private-sector employment.

This approach may move us away from a divisive discourse to an analysis of the details of each measure to reach an overall consensus.

Ravi Kanbur is the TH Lee professor of world affairs, international professor of applied economics and professor of economics at Cornell University. This is an edited version of an article published by the online policy forum Econ3x3.