Bank on this: A doctor stores breast milk at the human milk bank in Lima.

Her milk was the only thing Jen Canvasser could give her babies.

Born at 28 weeks, three months prematurely, Zachary and Micah each weighed less than a kilogram and were rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit. The boys were born so early that Canvasser’s milk hadn’t yet come in. She may have been a first-time mother, but she knew this: her babies weren’t going to receive formula. She believed that milk – specifically, her milk – would give them the best start in life.

Doctors told her to try to pump every two hours to get her milk to come in. So, every other hour, around the clock, Canvasser assembled the pump in her hospital bed, attached it to her breast and willed the milk to emerge. Nothing happened.

“It was really stressful,” she says. “These little, itty-bitty guys really needed the nutrition and I was told they would be given formula if my milk did not come in.”

After two days, during which the boys were given only minimal nutrients through tubes into their veins, Canvasser finally produced a few milky drops. After filling a tiny syringe, husband Noah took the lift down to the neonatal ICU and dabbed his wife’s milk on his sons’ lips.

In that first tense, terrifying week, Zachary and Micah’s doctors came to Canvasser with more bad news: her milk wasn’t providing enough nutrition for the twins. The doctors wanted to add a high-calorie fortifier to it to help the boys grow and develop. Canvasser agreed.

But instead of getting better, the boys began to get worse. They stopped breathing while asleep. They began to have trouble digesting.

Canvasser’s worry turned to panic on the cold Friday afternoon of the second week when Micah began vomiting. Things got worse over the weekend. By Sunday morning, his belly had become swollen and he was constantly throwing up. On Sunday afternoon, Micah was rushed to the operating room to have part of his bowel removed. Just two weeks old, he had developed a life-threatening disease called necrotising enterocolitis, which had killed parts of his intestines. The infection was so severe, his kidneys began to fail.

Premature newborns

Advances in caring for premature babies and very low-birthweight infants – defined as weighing less than 1.5kg at birth – mean that more of them survive longer. But this vulnerable group still has a high risk of necrotising enterocolitis. It affects about 1% to 3% of infants in the neonatal ICU and 7% of very low-birthweight infants, and up to a third of those infected will die. Numerous research studies have shown, however, that giving premature infants a diet exclusively of human milk significantly reduces the risk.

With Micah seriously ill, Canvasser finally asked the doctor about the fortifier in the boys’ milk.

“They called it a human milk fortifier. I assumed it was some type of benign extra vitamins or something that they were adding. I had no idea what it was,” she says. “So I asked: ‘What is this fortifier? Can you show it to me?’” The bottle they showed her was a brand of formula.

After searching the internet in the wee hours of the morning, Canvasser found a fortifier made from human milk and persuaded Micah’s doctors to switch after two weeks on the formula, but his tiny body was already hopelessly damaged. At 11 months old, having spent 10 of those months in intensive care, Micah died from complications of necrotising enterocolitis.

Micah’s brother Zachary, also given formula during his neonatal ICU stay, is now a healthy, thriving three-year-old. Still, Canvasser can’t shake her fear that the formula had something to do with Micah’s death, although there’s no way to be sure.

Statistics suggest that Micah would have had a better chance on an all-human milk diet rather than being fed with formula. But when a mother’s own milk isn’t providing enough nutrition for a vulnerable baby, the temptation is for medical staff to turn to formula rather than finding a source of human milk. Breast milk donation is on the rise, but will there ever be enough supply for all the babies who need it?

‘White Gold’: Breast milk may well be an elixir for premature babies. (Jorge Lopez)

‘White Gold’: Breast milk may well be an elixir for premature babies. (Jorge Lopez)

Sharing milk

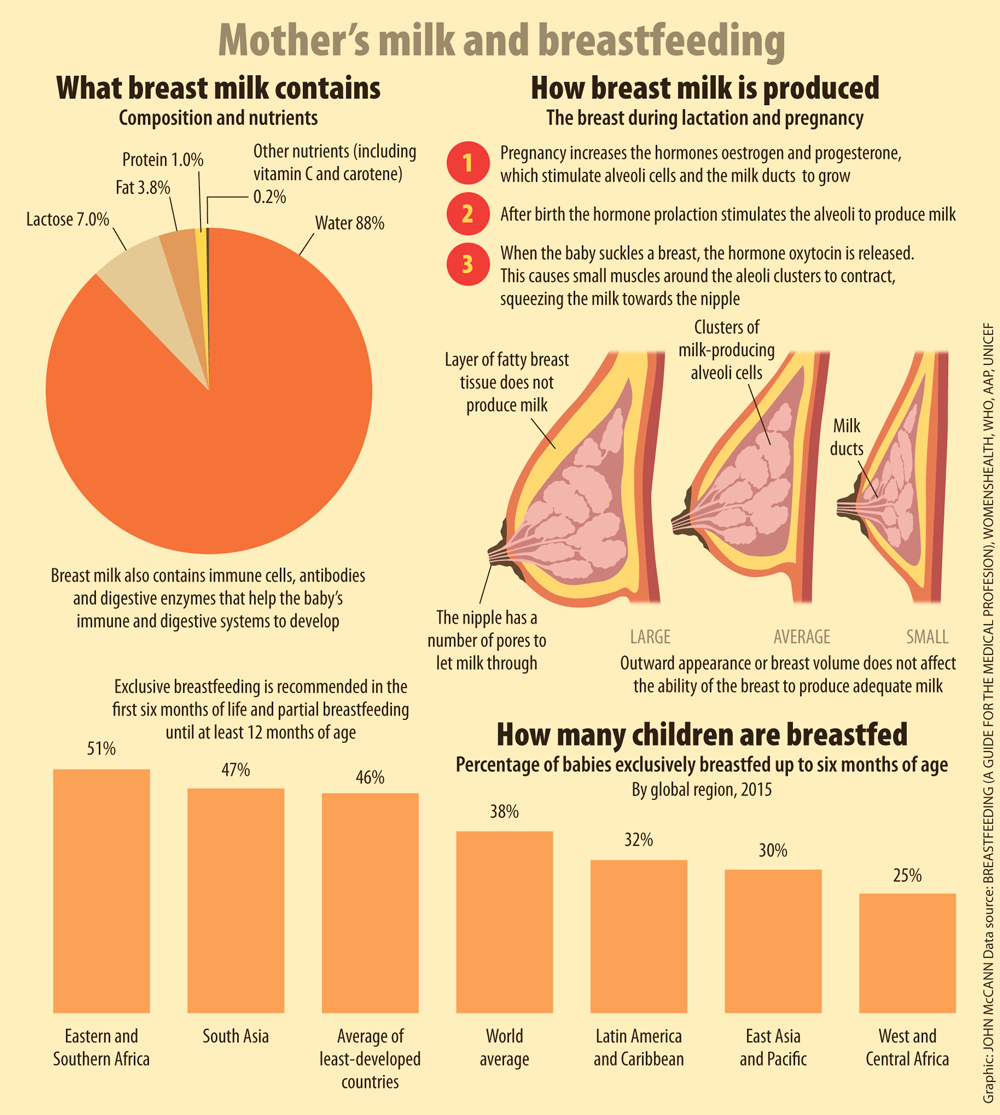

The maelstrom of hormones that help a woman give birth to her baby also tell her body to start producing milk. When the baby then sucks at her nipple, it stimulates the release of the hormone prolactin, which tells her body to produce more. Even so, it can take several days for milk to come in. For first-time mothers, those whose babies were delivered by Caesarean section and mothers of preemies, the milk supply can take even longer to start.

On the other hand, mothers can find themselves producing more milk than their baby needs, especially if they use an electric breast pump. This has given some the option of sharing the milk their child doesn’t need.

Sharing breast milk is not new. Women have done it for millennia, letting friends’ or relatives’ hungry children nurse at their own breasts. At other times, women would hand-express their milk into pots or jars to give to families in need. And wet nurses, often impoverished or enslaved women, were often used to provide milk for wealthy children, even if it was at the expense of their ability to nurse their own. In the early 1900s, hospitals and charities began freezing and banking breast milk for sick babies.

The Human Milk Banking Association of North America, which helps to run and accredit milk banks in the United States, has gone from dispensing about 12 000 litres of pasteurised donor human milk a year in 2000 to 112 000 litres in 2014. John Honaman, its executive director, says that “more people understand the importance of what pasteurised donor human milk can do for a child”. “We’re a bridge from the time that a child is born to the time that their mom can breastfeed,” he says.

Protective benefits

Breast milk can vary substantially from woman to woman. Mothers of preterm infants have milk that is higher in protein and fat. The composition of breast milk also changes as the baby gets older, becoming less nutrient-dense over time. But although donor milk isn’t identical to the baby’s own mother’s milk, it still has many of the same benefits, passing along valuable antibodies that protect the baby from disease.

Some parents are squeamish about giving their children milk from a stranger, but more and more neonatologists are framing it much more simply.

“We tell them that this milk is medicine,” says Amy Hair, a neonatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

The last few weeks of pregnancy are a busy time. Not only does the fetus continue to grow in size, organ systems are also rapidly maturing. Some of the last organs to finish developing are the brain, lungs, stomach and gut. Not surprisingly, this means that babies born prematurely often have difficulties with brain development, breathing and digesting food. Many preemies, especially those born before 32 weeks, have a digestive tract that is as thin and fragile as tissue paper, making them especially vulnerable to diseases such as necrotising enterocolitis.

Scientists aren’t sure what causes it. Mark Underwood, a neonatologist at the University of California in Davis and a leading expert on the disease, believes it is caused by an interaction between normal gut bacteria and the preemie’s still-developing immune system.

Human milk helps support the immature immune system, according to Hair and Underwood. Besides water, fat and lactose, the three largest components of breast milk, it contains many things that help fight disease, such as antibodies. It also contains human milk oligosaccharides, which can’t be digested by the baby but are the preferred food for many healthy bacteria living in the gut. If there are large numbers of healthy bacteria in the gut, that doesn’t leave room for disease-causing ones. Another component of breast milk is lactoferrin, which binds iron, making it unavailable to dangerous bacteria that need it in order to survive. In short, breast milk creates an optimal gut environment, especially in premature infants.

A premature baby is fed inside an incubator with donated milk in Rio de Janeiro.(Pilar Olivares/Reuters)

A premature baby is fed inside an incubator with donated milk in Rio de Janeiro.(Pilar Olivares/Reuters)

Not perfect

Still, Underwood points out, breast milk isn’t perfect for preemies.

“Preemies are unfortunately limited in the volume they can take, and the amount of nutrients in human milk really didn’t evolve for preemies. And so we know pretty clearly, [small premature] babies who get unfortified human milk, their rate of growth is going to be poorer than if they get fortified milk, and that has an impact on their brain development as well,” he says.

Trials in the 1980s and 1990s that first compared breast milk with formula found that preemies grew better on formula because it had more calories an ounce than breast milk. More recently, neonatal ICUs have begun to fortify human milk to ensure that these babies have the nutrients they need to grow and develop as well as all the benefits of breast milk.

“If you don’t focus on nutrition and give them the appropriate amounts of protein, they rapidly lose protein … The way you add the human milk fortifier, you can actually give high protein,” says Hair. “We know mother’s milk has antibodies, immune factors; while donor milk is pasteurised and has a little less of those components, it still has quite a bit of those immune factors.”

The business

Angel works on the fourth floor of an ageing brick high-rise building, at the end of a dim, narrow hallway. The windows of her office look out on to a leafy courtyard where physicians and support staff bustle in white jackets and scrubs. The noise from Angel working nearly drowns out all sounds of conversation in the room. Angel is a squat silver chest about waist-high. She is the $100 000 milk pasteuriser imported from Britain to Norfolk, Virginia. At North America’s newest milk bank at the Children’s Hospital for the King’s Daughters, Angel sterilises about 60 litres of milk every week.

The manager of the hospital’s mothers’ milk bank, Ashlynn Baker, gave Angel her nickname because she kills deadly microbes that can sometimes be found in donor milk, playing a key role in the process that takes milk from donating mothers and gets it to babies in hospital. Donors can bring their milk in person or freeze it and have it shipped overnight in a cooler at no cost.

“We have a lot of [military] moms come in wearing combat boots and fatigues, and they’re getting a lot of support and they’re pumping a lot at work and they’re bringing us a lot of milk,” says Baker.

To balance the milk’s nutritional content and maximise the antibodies the fragile babies receive, Baker pools the milk of five mothers before heating it to 62.5°C in Angel. The milk is then frozen and can be safely stored for up to a year. Just 30ml of milk can provide up to four feedings for a baby in the neonatal ICU.

The idea for this milk bank was planted in 2012. A statement from the American Academy for Paediatrics said: “All preterm infants should receive human milk. Mother’s own milk, fresh or frozen, should be the primary diet, and it should be fortified appropriately for the infant born weighing less than 1.5kg. If mother’s own milk is unavailable despite significant lactation support, pasteurised donor milk should be used.”

Not long after reading this, Baker held a baby who had been born at 27 weeks as he died in her arms from a disease that human milk might have helped to prevent. She herself was 27 weeks pregnant at the time. “I knew it was time to advocate,” she says.

Donations and profit

Baker and the neonatal ICU began working with the nearest milk bank – in Raleigh, North Carolina, a three-hour drive away. Not long after, the hospital’s board of directors asked her to give a presentation on the new protocol and, several days later, said they would put up the $500 000 to build a milk bank. In just 15 months, Baker had it up and running.

Local mother Stephanie Leverett has been their largest donor, providing more than 300 litres of milk her daughter Kennedy didn’t need. This equated to several thousand treatments. “It’s pretty emotional to think about it,” she says.

Becoming a donor was relatively easy. The Human Milk Banking Association of North America requires that all donors fill out a lifestyle questionnaire that asks questions such as what medications and supplements a mother takes and whether she smokes. Blood tests check for communicable diseases that can be passed through breast milk, such as HIV and hepatitis B.

Hair, the neonatologist in charge of nutrition at the Texas Children’s Hospital neonatal ICU, found that, after her hospital shifted to all-human milk diets, infants were able to move off feeding tubes more quickly and go home sooner. Preemies who exclusively received breast milk, whether from their own mother or from a milk bank, were also less likely to die from a number of causes.

Success

But what she found most promising was a dramatic fall in cases of necrotising enterocolitis. At her neonatal ICU, rates of the disease in very low-birthweight babies plunged from 10% to just 2%.

“There have been studies that show babies grow a certain way while they’re still in the womb … The challenge has been how can we mimic that and try to do the best job we can to give the nutrition as if the baby were still in utero,” Hair says.

“These babies don’t receive formula, they don’t receive cow protein, and they have amazing outcomes. They’re healthier. They have less infection. They grow better.”

It all seems very simple. Some babies need breast milk, which their mothers can’t produce; other mothers are producing more than their babies need. Human milk banks take the excess and give it to those in need. But as more parents and hospitals seek to use pasteurised donated milk, US milk banks have begun to experience shortages. For-profit milk banking companies have sprung up and milk can be bought and sold online, with fewer or no checks on quality or contamination. It’s becoming a lot more complicated than simply sharing.

In 2015 Sarah Keim, an epidemiologist at Ohio State University, published an analysis of 102 samples of breast milk she’d purchased online. Eleven contained significant amounts of cow’s milk. “That is a concern,” she says. “We were surprised to find the extent of that problem.” Once money becomes involved, she adds, it becomes more likely that people will adulterate breast milk to make a quick buck.

But more than that, does paying for donated milk change the nature of the relationship between the women involved?

Compensation

In late 2014 Medolac, an Oregon-based company, partnered with the Clinton Global Initiative to reach out specifically to low-income Detroit mothers and pay them for their breast milk. Although these payments were to compensate donating mothers for their time and effort, the idea behind this particular scheme seemed to be that, if cash-strapped women could make money from their milk, then more of them might breastfeed their children, if only to keep producing milk.

A local African-American mother, Afrykayn Moon, who strongly supported breastfeeding, immediately cried foul. The idea that the ability to earn money from breast milk would encourage low-income mothers to breastfeed their children was “absurd” to her.

“If I’m breastfeeding but my electric bill needs to be paid or my rent needs to be paid or my water bill needs to be paid, and I know I can sell my milk to this company and then I can get my bills paid, well guess what I’m going to do,” she says. “I’m going sell my milk to keep my bills up, and not a drop of that milk is going to go to my child.”

With Detroit’s low rate of breastfeeding and one of the country’s highest rates of infant mortality (15 out of every 1 000 children in the city die before their first birthday), Moon says that the city needs every last drop of breast milk.

The move also brought back a sinister association to Moon. Enslaved black women were often used as wet nurses for white children, leaving them unable to provide milk for their own children. “This is the face of slavery coming back,” she says.

Legally sound, but ethically?

Georgetown University philosopher and bioethicist Rebecca Kukla says, although some tactics used by companies might be perceived as exploitative, there’s nothing inherently unethical about a woman selling her breast milk. “There’s a difference between what someone does out of economic necessity and what they do as a private choice to make their life work,” she says.

It’s the choice 33-year-old Detroit mother Andrea Short made. She breastfed her first child, Jaden, with no difficulties, but when her daughter Johanna was born, she wouldn’t latch on. So Short began to pump to feed Johanna breast milk with a bottle. Soon, however, Short had pumped way more than Johanna would ever need and was running out of freezer space to store the milk. That’s when she found out that Medolac was willing to buy her milk.

Over several months, Short sold more than 148 litres of milk that Johanna wasn’t using, providing her young family with needed income. Although both Short and her husband, Jonathan, work full-time – she in a hospital and he as a firefighter – the family relies on welfare benefits to make ends meet. With part of the money from Medolac, Short bought a swing for their front porch that gives her children a safe place to play.

“I was grateful for the money and the opportunity I had,” she says.

Short, who is biracial, says she represents Medolac’s target audience and resents the implications that mothers who sell their breast milk would do so at the expense of their children. “I will always put my children first,” she says. “Always.”

Altruism?

Blood and tissue donation work entirely on altruism; many people think breast milk should be no different. John Honaman says the Human Milk Banking Association of North America sees no place for profiting from breast milk, and thinks the system is at its best when mothers who have received donated milk decide to donate in turn.

“If we were faithful to the needs of a community, we would always want to be in a position whereby the need is associated with the supply because you have a perfect circle,” he says. “Moms need to give; kids need to receive.”

Morgan Bryan is a schoolteacher in Houston. She saw the benefits of an all-human milk diet for her twin boys, Austin and Jonah, who were born at 24 weeks. Her milk hadn’t come in and with the agonising stress of watching her tiny, vulnerable infants barely cling to life, she had trouble producing any milk at all.

So when the doctor asked the Bryans if they would be okay with their children receiving donor human milk, they didn’t hesitate.

“I didn’t ever think twice. They had multiple blood transfusions and it’s the same thing. And if that is what they needed, that is what we’re going to give them,” says Bryan. “I was so excited that [they] could take milk, I was in immediately.”

Several days later, Bryan was producing enough milk to be able to feed her sons with her own. The twins also received a fortifier made from donor human milk. As a result, Austin and Jonah sailed through the high-risk period for necrotising enterocolitis.

At eight weeks, Austin died of an unrelated infection, but Bryan was so grateful for the donor milk her sons had received that she donated her own excess milk to the Texas Children’s Mothers’ Milk Bank.

“There’s just a nice feeling,” she says, “because I know that my kid needed it at one point and I know that when you’re sitting in the neonatal ICU and you can see all the other babies, you know that those babies are getting it as well.”

This is an edited version of a story that first appeared on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence. The original story can be found here: mosaicscience.com/extra/rise-and-fall-and-rise-breast-milk-banking