Johannes Phokela at his Selby

Johannes Phokela’s studio is in Selby, an industrial area of Jo’burg that has remained untouched by the gentrification creeping into the inner city. It’s probably why he is able to afford a studio the size of a school hall.

It is so large that once you’re standing in it, the noisy traffic artery outside becomes a distant thought. The classical music on the radio and the paintings that evoke works you only see in European museums transports you far beyond this factory setting.

Paintings in different stages of evolution are propped up against the walls and his resources, art books (Caravaggio, Bruegel) and newspaper cuttings are on long tables dotted around the room. During our conversation, Phokela riffles through these documents looking for a reference – with Phokela’s work, it is always about the original reference, which is either drawn from art history’s canon or the Daily Sun and other newspapers.

Combining high culture with lowly pop culture is his thing. Being aware of the origin of his art plays a huge role in understanding the game Phokela plays. He turns ordinary events, as reported on in a newspaper, or even a cheesy image from a recipe book, into a scene that ought to be hanging in the Louvre – but with it he undercuts the moral authority of a masterpiece, which he almost always associates with imperialist ideology.

Western painting is the basis for Phokela’s art. He usually renders it in the classical figurative traditions spanning from the Renaissance to the baroque. He subverts, satirises and exploits the works of the masters to make a comment on power relations then and now.

But he also appears to admire their works. He confesses to loving Bruegel, as he pages through a book on the artist’s art, pointing out details that excite and amuse him. Painters are often caught in this push/pull between loving the foundations of their medium and wanting to overturn it.

“Painting is hard. That is why so few people actually do it,” says Phokela in his distinctive accent with its cockneyish lilt, one of the remaining traces of decades spent living in London, where he studied at the Royal College of Art. He visits the United Kingdom every year and considers it a home: “I have more friends there. I might still go back and live there again.”

Painting has enjoyed something of a revival, but the new generation of emerging painters, mostly in Cape Town, are into abstraction, or a sort of kitsch impasto figurative style with rococoesque excesses. It is hard to be sure, but most of these young painters probably can’t paint – or can’t paint like Phokela, who seems more interested in overturning the canon than taking ironic swipes at it. There is a difference.

Exciting Recipes

You can’t help wonder whether his education and exposure to Western art in London accounts for his work being so haunted by it. Or is it that it presents the ideal visual plane on which to dissect Africa’s relationship with Europe?

Phokela treads a fine line between mimicry and mockery. He reproduces figures, scenes and the classical mode with a post-colonial revisionist twist, which ultimately allows him to raise a finger at the West.

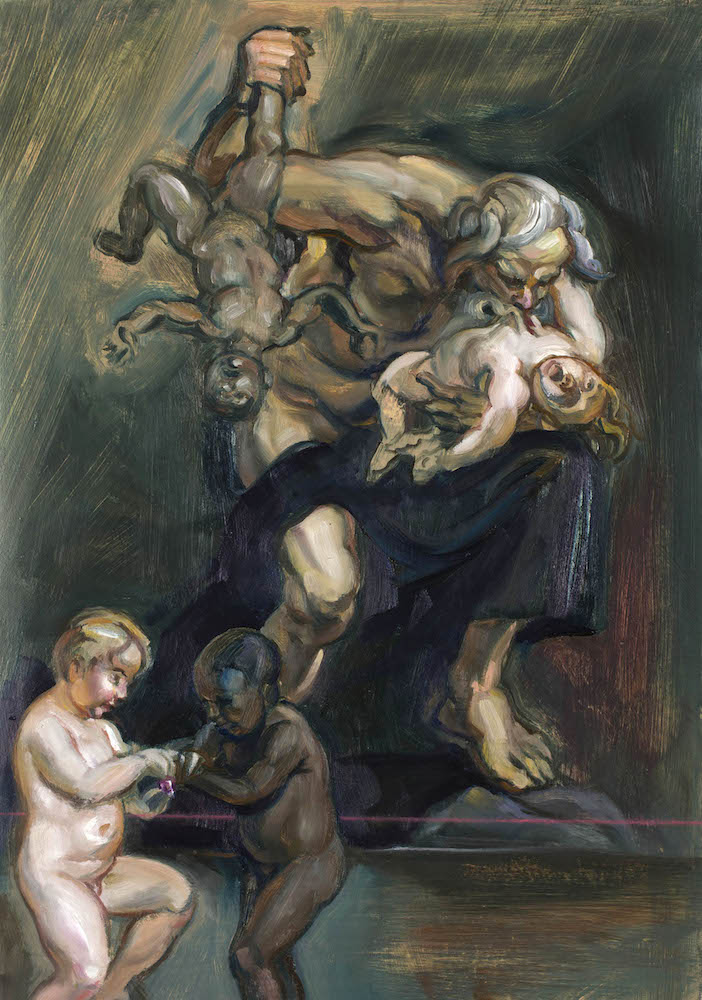

An example is the new suite of paintings he produced for the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, held this month in London, which included his take on Goya’s famous image, drawn from Graeco-Roman myth, of Saturn devouring his children. Phokela adds more children, turning the scene into one that exposes how violence, brutality and bigotry is normalised by art.

Not that he would put it that way. Like most artists, he won’t tell you what he is “saying” in his art. He won’t explicate what’s there. After two hours in his studio, I left without a suitably political soundbite. To some degree, his art is not about the viewer, but is the result of an elaborate game designed to amuse himself – he has a dark sense of humour and enjoys his own jokes. (Don’t we all?)

Laplandish Dream, which shows Santa Claus on holiday in South Africa, best illustrates Phokela’s macabre streak and the manner in which his art is a quasi-collage of references from art history and newspaper stories. This Santa’s face echoes that of a man who was arrested for molesting girls while working as Father Christmas over the festive season. His body is that of a Titan, the race of god-giants (Saturn was one) that were a popular subject for Italian artists of the Renaissance.

In other words, again Phokela exposes the corruption of revered (Western, white, male) figures – Santa and Titan. He adds another interesting layer to the story by placing a topless black woman behind Santa; she is hanging up washing.

“She could be a domestic worker but she could be his wife – the child in front looks coloured, so he could be their son. I always start with a simple story and my interventions are meant to bring up a lot of common issues [that are] symbolic of what is going on today and painted in a classical way.”

This Santa-cum-Titan figure could be reading Vanity Fair, Phokela points out with a laugh. The humour is so clearly a device to undercut the politics.

Saturn Devours His Children

His upcoming solo exhibition at Jo’burg’s Art on Paper, titled The World of the Sacred and the Profane, will include his contemporary subversion of the Three Graces so popular with neoclassical painters. He has recast the race of the women – a black and Indian woman are added to the composition. The former figure is modelled on Boity (TV star and socialite Boitumelo Thulo), who caused a furore when her “booty” went on show in Marie Claire magazine as part of a “feminist” campaign that backfired.

Phokela doesn’t seem to have a strong opinion about the incident; I suppose he is just interested in it because of the attention it ignited and is curious to discover how a feminist conversation might intersect with a traditional representation of a naked woman. Which of these is considered art, as opposed to a complicit and insidious form of objectification?

In this way, Phokela’s art collapses art history’s European traditions into contemporary African popular culture and concerns, feeling out where they overlap or contradict each other. Phokela wants to see how the juxtaposition might reflect the ways the past informs the present: it looms as an irrepressible foundation that has shaped our world views.

He used to reflect this meta-commentary in the bold white lines or frames he would place on his renditions of classical works. At times, this was his only intervention. “These grids changed the way one views the image; they added an optical effect,” he says. “They put the frame on the inside.”

This is what he did with one version he painted of Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, which is now part of the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s collection. Another more curious version of this famous painting and scene will form part of his new exhibition: it presents Maximilian’s father, the Archduke Franz Joseph of Austria, whose assassination sparked off World War I.

The coincidence that these two historical figures met their ends so violently, and in the course of such significant events, made Phokela create the link between them. He does so by inserting into the image a Charlie Chaplin character wielding a 1940s film projector, who projects the assassination of the archduke on a wall behind Maximilian.

This intervention amuses Phokela no end. It also demonstrates how collapsing time and space is probably at the core of his work. Will he always use the Western art canon to enact this? “Probably,” he says.

The World of the Sacred and the Profane opens at Art on Paper on October 31 and runs until November 21.

This review was generated as part of an initiative run by Mary Corrigall @IncorrigibleCorrigall in which galleries and curators sponsor reviews for publication. They have no input into the content of the review.