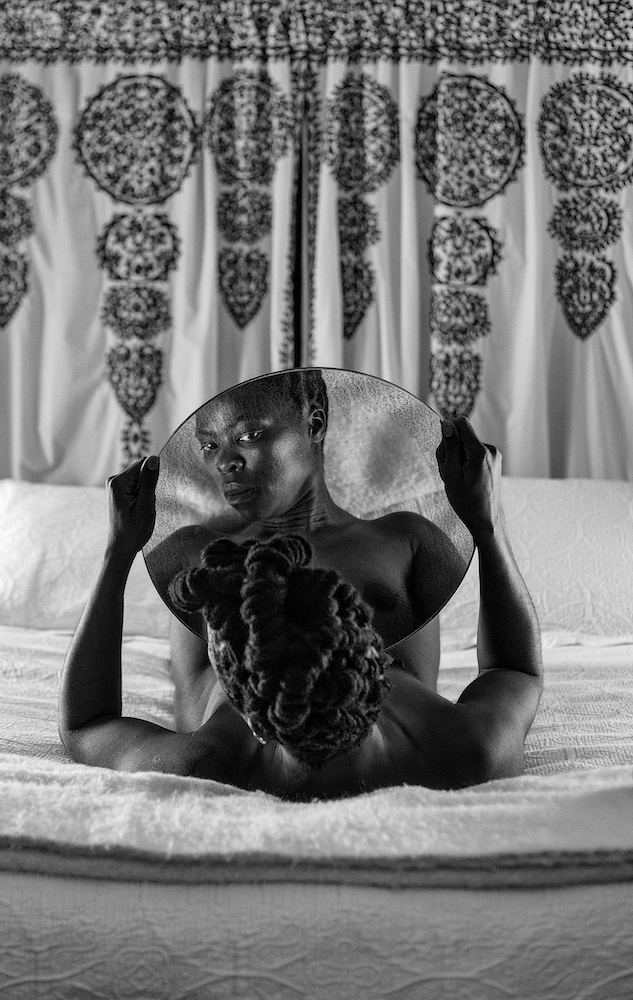

Phindile I

Somnyama Ngonyama, Zanele Muholi’s latest work, finds the activist photographer, who has spent the most part of her career documenting the lives of South Africa’s LBGTI community, turning the camera on herself. The resulting body of work, though deeply personal, underpins her connection to the very community she has dedicated her work to, allowing her to look at further nuances in the intersectionality of race and gender. The scope of Muholi’s new work, though departing from the autobiographical, resonates across the diaspora and beyond.

The exhibition also includes Brave Beauties, a collection of work looking at trans women and feminine gay men in South Africa and the beauty pageants that celebrate their lifestyle.

She spoke to the Mail and Guardian on the eve of her exhibition’s opening (which was on November 19).

When you have been taking photos of people in the LBGTI community, you have likened it to taking images of yourself. Can you expand on that idea, especially since the photographs you are taking now are of yourself?

I’ve always been part of who we are, nje as members of the black community, before our sexuality, before our gender expression. In my head, there has always been that longing to see myself as a part of history – South African visual history.

I grew up in a space where not many ordinary people made it into the mainstream space unless there was drama or tragedy of some sort. So I just wanted to produce images that feature likenesses of ordinary people in different settings without any glossy kind of [effects].

Bester V, Mayotte, 2015

If I should document people’s visuals, I should be one of us and shouldn’t speak as an outsider because, obviously, documenting LGBTI people comes with its own challenges.

Did that view have anything to do with making sure that you were never the only one with a camera in your community?

I grew up eMlazi [south of Durban]. Not many people had cameras. When I had access to cameras, I just felt the need [to make sure] that those people who are featuring in my work should get equipment and further document. Because there are moments when I might not be the to take photos but there is a person who is.

You speak of a fear of taking self-portraits. Was that purely in the history the images would bring out, or was it something more personal?

It’s deeply personal and it’s connected to South African history. I’m talking about issues that are happening at home. At a time when I photograph myself in different spaces where I’ve been at, that particular incident is connected to a place in history.

Some of the images were captured at the time when I was deeply thinking about the Marikana case, for instance. When I was thinking about the black lives lost and who becomes a perpetrator.

Bona, Charlottesville, 2015

In other cases, I was thinking about my mom who becomes a domestic worker in a setting that’s white. She never had an opportunity to be celebrated. So I had to produce an image that paid homage to her as a living being, who contributed towards the economy and labour of the people in this country.

There is an image where I look like my father whom I have never met, who died when I was a couple of months old. So that is my connection to my background.

The very same image is also about my brother who died when he was only twenty years old. A car knocked him down and some rich kid from the neighbourhood got away with murder because he was rich. There are mixed feelings. And I gendered these images which is not my 24-hour reality.

Another case that pissed me off was of the two young students from the University of Pretoria who dressed as Sara Baartman and they painted their faces black. I thought of what our responsibility is as black artists in this country and how then do we respond to such negativity. So I produced an image that says we don’t mimic to be black, this is who we are.

How did you try to explore the connection between what was happening in Marikana and police brutality in America?

With Marikana, specifically, what triggered me is the queer question that has not been asked. There have been some theories and writings on miners looking at same-sex relations, which were not called homosexuality, as such. So I was thinking to myself, living in a democratic country that is South Africa, what if a gay man came forward to claim one of the bodies of the deceased, as a life partner or people who were in a long-term relationship?

Thembeka II, London, 2014

How would the nation read that particular incident? Are there any bodies that were queer, that were lost that day? Could we mourn those people and proudly say that this person was a member of the LBGTI community. So I was thinking about how these struggles are connected because at the end of the day it is about people’s lives.

You used your hair as part of the idea of headgear. Can you talk about the use of headgear in this exhibition not only as a framing device but also as a way to explore subjugation?

I was also exploring it as a form of resistance. I like natural hair. It comes with a history of where we come from. At school they’d always say, “Cut that black hair,” but no one ever explained anything. It also brings back the notion of pencil testing and ‘kaffir hare’. How people read it, putting their own meaning to black hair without even understanding it.

[I also look at] the whole thing of covering women’s hair, the idea of respectability of some sort; the bride (umakoti) must always cover up; we must always trim when someone dies to remove the bad luck – but nobody ever explains that. So I wanted to use different materials for the viewers’ focus to go towards the hair to make viewers question it.

In preparing for the photographs, was there any application of blackface or make up to drive your point?

No, we just increased the contrast. If there is anything applied, it would be gloss because sometimes the lips vanish, depending on where the light falls or comes from. I can’t darken my face. I am black. There are no make up artists, no heavy make up. No Plascon. In some instances, I’ve used flour to avoid the shines. So I’ve stuck to common materials. In the one image (Bester 1), I used toothpaste on my lips.

Dimpho Tsotetsi, Parktown, Johannesburg 2014

Can you talk about the titling of the work. Who is Bester, for example?

Bester is my mother’s name. She was born in 1936, during the Battalion War. So what used to happen at Home Affairs was that they would give you whatever name they thought was good for you. When you applied for a job, someone, either a Home Affairs official or your boss, would give you this new name.

Some of the other works are named after my brother and my sisters and some of the other women I grew up with, who were connected to my family. Those are the beautiful black women that never made it to Ubuhle beNdalo [the beauty page of Ilanga laseNatali] and Bona magazine that I grew up reading. I really liked those pages. And now when I project these images I wonder [about older times] because it was the high time of [bleaching creams such as] Ambi and He-Man, Eskamel – products that disfigured black people’s skin. In many ways my work is statement against those things.

So why have you chosen to combine the two, Somnyama Ngonyama and Brave Beauties?

I wanted to photograph members of the community whose interest was also beauty. These are young trans women and feminine gay men who exist here and I wanted to bring that subject matter as a topic of discussion to create dialogue.

These are beauties that have won different pageants but have never gained much recognition. And in these pageants they have entered over the years, there is no earning of big prizes or trips overseas, like they do in Miss South Africa and yet we say the LGBTI community is recognised by our Constitution in South Africa.

Yaya Mavundla, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2014

Somnyama Ngonyama is on show at the Stevenson gallery in Braamfontein, Johannesburg until 29 January 2015.