When Oscar Pistorius was acquitted of murder by Judge Thokozile Masipa on September 12 last year, he sobbed. Cameras were trained on him as he bent over in the dock, his shoulders heaving. His trial had been punctuated by his tears and vomiting, but on that day his crying had a different quality. He seemed deeply, and viscerally, relieved.

In the eyes of the law, he was not a murderer. That label, which he so clearly feared and resisted, could not be attached to him. But now, a year and nearly three months later, it has been.

Just after 10.30am on a sunny day in Bloemfontein, Supreme Court of Appeal Judge Eric Leach read out the words that have seismically shifted Pistorius’s fate – and found the former Olympic and Paralympic superstar guilty of Reeva Steenkamp’s murder, rather than culpable homicide: “The accused’s conviction and sentence on count one are set aside and replaced with the following: ‘Guilty of murder, with the accused having had criminal intent in the form of dolus eventualis [indirect intent].”

The court has referred the case back to Masipa for sentencing. Pistorius faces a minimum sentence of 15 years in jail – unless there are “substantial and compelling circumstances” justifying a lesser sentence.

His defence team is likely to argue that Pistorius’s previously clean criminal record and the fact that he has already spent a year in prison for culpable homicide should be grounds for lessening his sentence – as should Masipa’s own finding that he has shown remorse for killing his girlfriend.

Pistorius’s family and legal team have declined to comment on the appeal court’s decision, and are likely to only consider a possible appeal of that ruling to the Constitutional Court once he has been sentenced. Such an appeal can only be made on constitutional grounds. With Pistorius’s lawyers having already revealed that he has been left financially devastated by his trial, his prospects of being able to launch such an appeal are questionable, but not impossible.

It would seem that the Pistorius saga may be far from over.

The appeal court was by no means immune to the sadness beneath this nearly three-year story.

Leach began his ruling with words not typical of his court’s judgments: “This case involves a human tragedy of Shakespearean proportions,” he said. “A young man overcomes huge physical disabilities to reach Olympian heights as an athlete; in doing so he becomes an international celebrity. He meets a young woman of great natural beauty and a successful model, romance blossoms and then, ironically on Valentine’s Day, all is destroyed when he takes her life.

“The issue before this court is whether, in doing so, he committed the crime of murder, the intentional killing of a human being, or the lesser offence of culpable homicide, the negligent killing of another.”

Steenkamp’s mother, June, sat in the court’s front row for the 53 minutes that Leach took to explain the court’s decision to find Pistorius guilty – of murdering the human behind his toilet door, not her daughter.

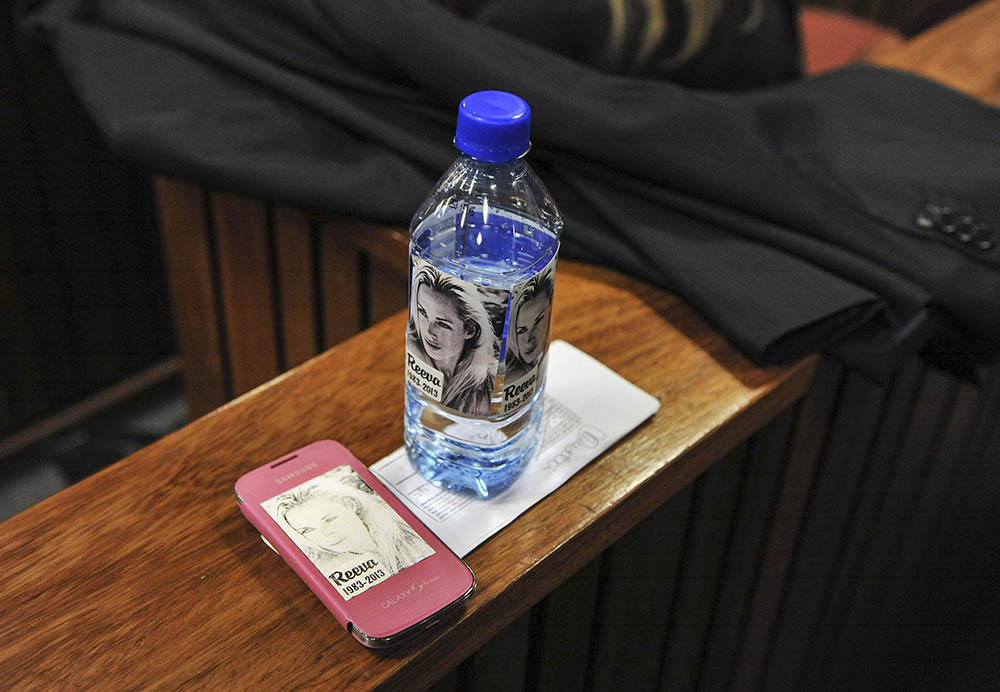

The prison cell occupied by Pistorius after being convicted of the culpable homicide of Reeva Steenkamp. (Sydney Seshibedi, Reuters)

Prosecutors abandoned their case that Pistorius deliberately murdered his model and law graduate girlfriend when he fired four shots through his closed toilet door in the early hours of Valentine’s Day 2013.

Instead, they accepted his account of the shooting – that he had fired in the belief that there was an intruder behind his door – and argued that he was guilty of murder committed with dolus eventualis.

“If the aim was higher, if there wasn’t a door, I would have made different submissions,” prosecutor Gerrie Nel told the court a month ago, in response to questions about whether the state was still arguing that Pistorius had direct intent to kill Steenkamp.

“But the submission we made is that there was foresight, that a person standing behind a door in a small cubicle … if you fire four shots into that, a person will die.

“The accused went ahead and fired four shots, not just one.”

Masipa had found that, because Pistorius had not foreseen that Steenkamp could have been standing behind the door when he fired, he could not be convicted of committing murder with indirect intent. Instead, she found him guilty of culpable homicide, or grossly negligent killing.

But the appeal court found that this interpretation was wrong.

“What was in issue, therefore, was not whether the accused had foreseen that Reeva might be in the cubicle when he fired the fatal shots at the toilet door,” Leach said, “but whether there was a person behind the door who might possibly be killed by his actions.”

Leach said the evidence of police ballistics expert Captain Chris Mangena clearly showed that Pistorius must have foreseen that shooting into his tiny cubicle would result in the death of whoever was behind that door.

“Having regard to the position of the bullet holes in the door, the marks the bullets left in the toilet cubicle and the position of the injuries on the deceased’s body …[Mangena] determined that the deceased must have been standing behind the door when she was first shot and then collapsed down towards the toilet bowl.

“Although the precise dimensions of the toilet cubicle do not appear from the record, it is clear from the photographs that it is extremely small. And it is also apparent from the reconstruction and the photographs … that all the shots fired through the door would almost inevitably have struck a person behind it.

“There had effectively been nowhere for the deceased to hide,” the judge said.

He added that Mangena also testified that the Black Talon ammunition Pistorius had used “would penetrate a wooden door without disintegrating but would mushroom on striking a soft, moist target such as human flesh, causing devastating wounds to any person who might be hit”.

The court, he said, could therefore not accept that Pistorius would not have known that firing those bullets into his tiny toilet cubicle would kill the person in it.

Reeva’s mother June sat in the front row of the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein. (Antoine de Ras, Reuters)

Pistorius’s defence, that he had acted to protect himself and Steenkamp, was rejected by the court as “irrational”.

The ruling was momentous for everyone involved in this trial – but its announcement bore none of the drama that defined Pistorius’s murder acquittal.

Pistorius was convicted of murder far away from the cameras that captured almost every moment of his trial. Under house arrest in his uncle’s home in Waterkloof, Pretoria, he is very likely to have watched the ruling being broadcast live on television.

He has been under correctional supervision for nearly two months and would have remained so until 2019 had Masipa’s original verdict and five-year sentence stood.

Footage of Pistorius leaving his uncle’s home to report for community service show the effect that his year in prison has had on him: he is gaunt and his skin seems grey. Now he faces the almost certain possibility of several more years behind bars.

And that is something the prison authorities are acutely conscious of. Just two days before the appeal court decision, the correctional services department took the unprecedented step of allowing media into the Kgosi Mampuru II Prison where Pistorius had been jailed.

Correctional services acting regional commissioner Mandla Mkabela told the assembled reporters that the department was showing them the athlete’s cell – positioned next to the one formerly occupied by notorious Czech convict Radovan Krejcir – “so you can report from an informed perspective … not from stories by unnamed sources”.

The department was particularly unhappy about reports suggesting that Pistorius had been given special treatment and had made, to quote one weekend newspaper, “diva demands”.

That claim, Mkabela repeatedly said, was simply not true.

“This is inaccurate reporting and it is time-consuming for us. It is not good for the public out there, society, because they are being fed with incorrect information and when offenders are placed back into society, then they face rejection and resistance because it seems they are not rehabilitated.”

Mkabela was at pains to stress that Pistorius had not been given a specially converted bath, as alleged in certain media reports.

Again and again, he emphasised that the 29-year-old was the only double amputee inmate the department had ever housed. Apart from that, there was nothing special about Oscar Pistorius.

“High-profile offenders come and go in correctional facilities throughout the country, and it is not about one offender. We have got 35?000-plus offenders in the region and we really cannot spend our energy and focus on one offender.”

The first stop on the department’s tour of Kgosi Mampuru II was, however, the hospital section that housed Pistorius.

“Now you’re going to see what you’ve all come here for,” an excited prison official told the assembled group, which had to be divided up and led past the cell.

Reporters thronged around Pistorius’s cell in the prison’s hospital, taking endless pictures of his bed, sink and cupboard. “That pillow looks extra fluffy,” an international correspondent joked with a warder.

He looked aghast. “It’s a normal pillow,” he said. “There’s nothing special about that pillow.”

It was a strange and comic encounter in a strange and tragic place: the cell where the man once lauded as an international hero had spent 12 months studying, sleeping and watching television series.

Pistorius may very well return there in the coming months, with the label he feared so much now attached to his name: fallen hero and murderer.