In Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s latest exhibition, Beacon, we are introduced to seemingly minimalist work whose thematic offshoots range from questions of space and landscape to imagined futures and the types of existences that they may hold.

The overriding theme is utopia and as the title of her work indicates, the message is a call, a signalling towards imagining what this utopia or utopias could be.

Sunstrum’s work itself comes as a contribution to a project for the collaborative Minga, Exploring Utopia initiative, which involves 21 galleries worldwide, including the Visual Arts Network of South Africa (Vansa) in New Doornfontein, where her work is being exhibited.

Minga, which means “to work together for the common good” is a Hispanicised iteration of the Quechua concept mink’a, which in turn refers to the type of traditional-communal work in the Andes meant in most instances to favour the community as a whole.

The initiative’s aim is to explore notions of utopia to generate wide-ranging perspectives about this concept and ultimately to share these between its collaborating partners.

What is utopia and how does one go about imagining it? Are there any existing utopias or are they merely places we are yet to find or, perhaps, never will find?

Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, quoting Spanish Baroque writer Francisco de Quevedo, wrote that utopia is “a Greek word which means there is no such place”.

A modern-day utopia

Sunstrum, in Beacon, and in many ways as an expansion of previous work, notably Territory of Possibility, presents an intelligently layered response through a series of installations. The installations, which include a large drawing on the gallery wall, are arguably what lend the space the minimalist and almost bare feeling it has when you enter it for the first time. But on close inspection there is quite a lot being said and suggested by the work.

For one thing, and an important clue at that, Sunstrum’s response takes its inspiration from the fake travel pamphlet Visit Port Watson!, authored by the anarchist Hakim Bey (Peter Lamborn Wilson). In this pamphlet Bey presents an imaginary island somewhere in the Pacific, named Sonsorol. A modern-day utopia “with a population of 2 000 people, with no formal currency, no army or police force”.

The island is devoid of what may be termed our historically normalised societal and political existence.So appealing was this imaginary island that Bey received inquiries about the island’s exact location. Bey had to remind those inquiring about the island that utopias do not exist.

The evidence of their allure suggests that there is an undeniable yearning for alternative spaces, alternative thinking about space(s) that goes beyond the catchiness of utopia.

This alternative thinking can perhaps be discerned in Sunstrum’s description of her practice when she notes: “I am interested in the idea of locating utopia within the space of imagination rather than physical space. The space of imagination opens radically vast territories of possibility. This space of imagination allows for multiple, simultaneous ‘utopianisms’.”

Unpacking utopianism

What are utopianisms? According to theorist Bill Ashcroft utopianism, as opposed to utopia, “is fundamental to human consciousness because humans are always striving forward, anticipating, desiring. While utopias exist in the future, utopianism (anticipatory consciousness) is heavily invested in the present.”

In other words, it is the aforementioned “yearning” that, while occupied in an imagined future, is nevertheless rooted in the present.

With this in mind, one is able to approach Sunstrum’s work with the openness its interpretation requires. The glass jars, half-filled with water and glitter and placed on the floor with light bulbs hanging above them, catch the eye first. The water inside the transparent jars suggest the potential for fluidity in the space, a fluidity that may be physical or even imaginative.

One cannot help but also associate the glitter on the water, its luminance multiplied by the light bulbs above, with the often romantically invoked adage that the future looks bright.

Considered with the electronic sound emanating from the installation on the immediate left when you enter the space – two boards adorned with the imagery of what appears to be particles in motion, a record player with a half disco ball spinning on top along with the record – it is clear that the installations are intended to speak to each other.

A message from the past

The combination of material used in the sound installation presents another reading, that of the almost contradictory manner in which the past – old technology of a record player and an LP with electronic-sounding music – invokes the future. This is surely not coincidence.

When considering the drawing on the wall, for example, with its central subject of an outlook post, there is an aesthetic reference to Renaissance intellectual and artist Leonardo da Vinci’s use of blobs in many of his study sketches of water and wind.

Sunstrum, in elaborating on this, says the use of these blobs is a way of “appropriating from the past” and, more specifically, borrowing Da Vinci’s idea of using blobs to depict analogously those aspects of perceived space that one cannot easily capture or illustrate in tangible forms.

This is an important insight because, in expounding upon the concept of utopianism, its inherent yearning that is rooted in the now, Sunstrum recognises the potential of using the past as a future-imagining tool.

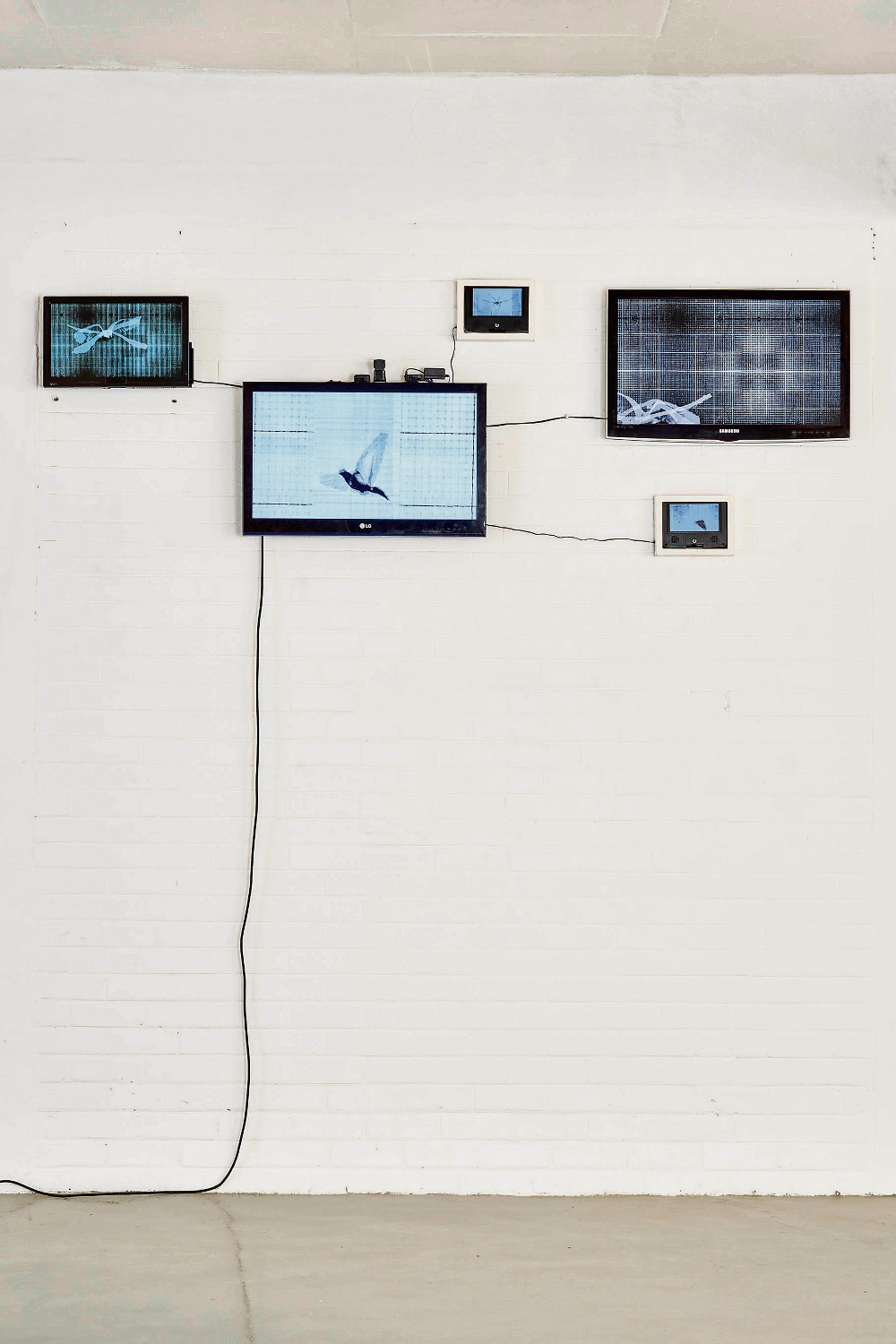

The remaining work, a video installation of an animated homing pigeon in flight across numerous screens, is no different in its simultaneous invocation of past and future. One of the screens has a Morse code message repeated over and over again. It is a message from the past, which is ultimately what our present will soon be to the future.

One may argue that it is, when read in the entirety of the exhibition, an undeniable calling, summoning us to consider what the future might be if we imagine or rather, if we re-imagine it.

Beacon is at Vansa, 6 Verwey Street, New Doornfontein, until January 15. Visit vansa.co.za