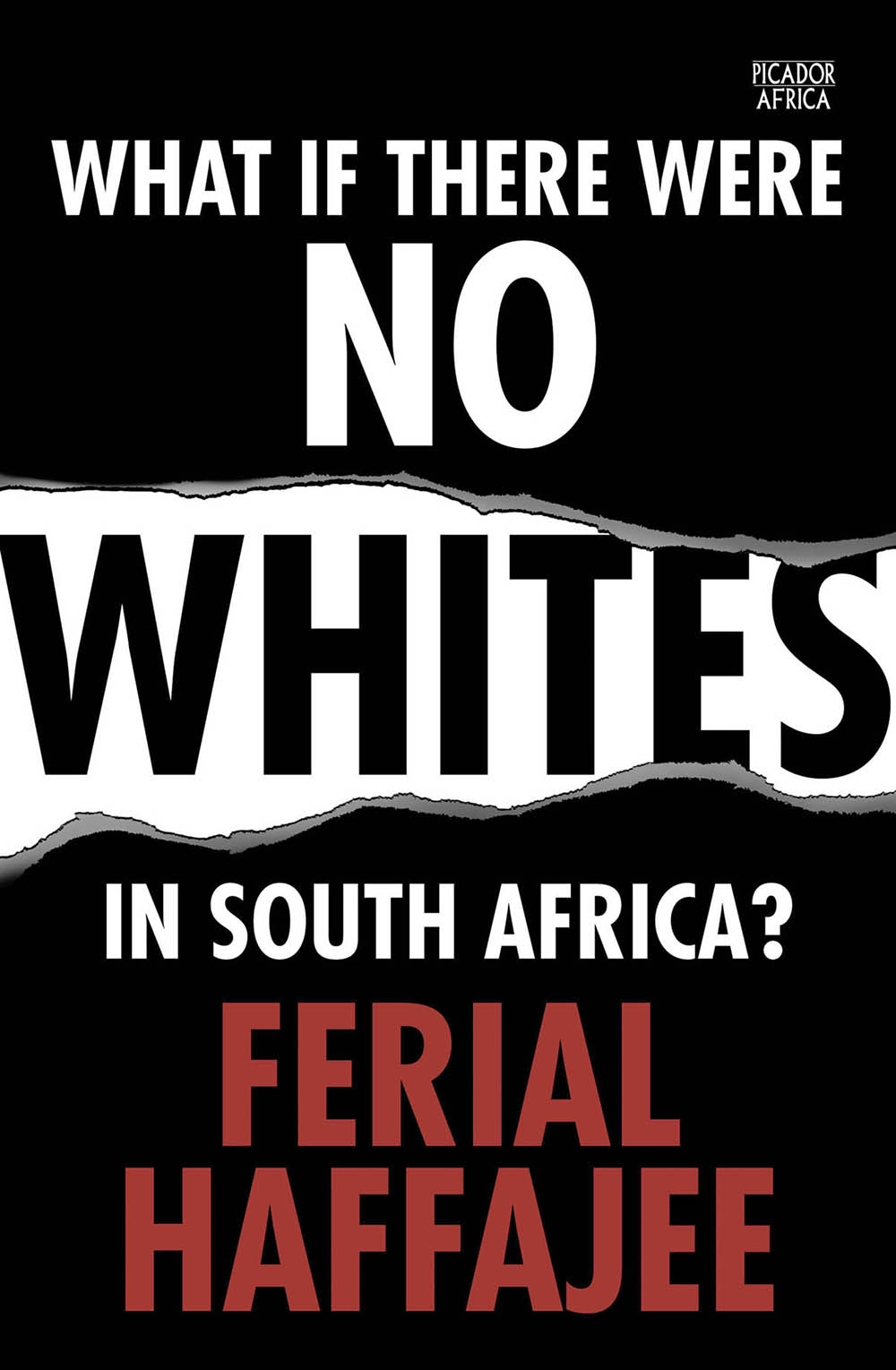

WHAT IF THERE WERE NO WHITES IN SOUTH AFRICA? by Ferial Haffajee (Picador Africa)

Ferial Haffajee came to the Weekly Mail, as it was then, as a trainee in the 1980s. She left and returned once or twice, eventually settling in for a stint as editor of the Mail & Guardian in the later 2000s, then leaving to become editor of City Press, where she still presides.

Having worked with her for all those years, I might have to make a declaration of interest before getting on to her book, but it’d be fairly simple: we worked together and, yes, we had some disagreements (particularly about design and typography), but we’re still friends and I have a high regard for what she has done in the South African media.

Haffajee talks in her book of those early days at the Weekly Mail and her progress from there; she speaks of her younger self, coming from a poor Bosmont home, going to Wits University and getting politicised, becoming a journalist. There’s an amusing passage in which, as a young journalist for the Weekly Mail, dressed in a Che Guevara T-shirt to visit the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, she is instantly recognised as being from the Weekly Mail. (It’s especially amusing when you call to mind the glamorous Haffajee of today.)

The autobiographical line stretches throughout What If There Were No Whites in South Africa?, for Haffajee is questioning what she believed, as a fighter for nonracism, back in those days – a fight that seemed to have been won in 1994. She sets those ideals against what she’s hearing today: the continued resentment against and blaming of whites for being the “haves” while most black people are still “have-nots”, and the discourses of blackness and whiteness.

This is not the Africanist question raised by the Pan Africanist Congress and others who set themselves up against the communist-influenced (and thus white-influenced) ANC of the early 1960s, but rather a neo-Bikoism developed by the likes of Andile Mngxitama, to mention only its most vociferous proponent. It redefines the content of these apparently racial categories: “blackness” becomes a term for all the oppressed and exploited, and “whiteness” is the word used to describe all the white (Western?) privilege that still exists and the inherited economic structures that perpetuate it, as well as the kind of government (the ANC, obviously, for Mngxitama) that, apart from a bit of deracialising of capital, rules in a manner not at all unlike a colonial regime.

Is this the death of the “rainbow nation” dream? Why are so many people so angry and so engaged in this battle, if, as Haffajee points out, the past 20 years have seen significant advancement and upliftment for black people? Why are so many people (including, often, the ANC) acting as though the apartheid state were still running everyone’s lives?

Haffajee explores these questions in a novel fashion, convening discussions with key players and thinkers on the matter, recording their dialogues and relating the arguments that take place to try to unpack or unpick the issue.

This is an accessible way to work through the discussion, good for the reader who doesn’t necessarily want to have to wade through a lot of political theory and competing statistics – the endpoint of which, anyway, is usually one of only two conclusions: the left says we need a socialist revolution, which will solve all our problems, and the right says we need economic growth, which will solve all our problems.

Haffajee’s symposium method can also be a tad confusing, however, as a myriad names come and go, quotes attached; it’s easy to lose track of who’s arguing what, and sometimes it feels as though one’s trapped in some terrible racial-sensitivity workshop for days at a time. It’s clear, though, that this is a conversation South Africans still need to be having: 1994 did not end it.

The question of the book’s title is a “thought experiment”, and obviously it can be answered either historically or in terms of the present and the future. You can speculate about what South Africa today might be like had there been no colonisation and no apartheid, but that’s a rather empty exercise in counterfactual history, and doesn’t take one very far. Ask the question in the present tense, as it were, and the answers get more interesting.

If there were no white people in South Africa, if they had all somehow disappeared in 1994 and their wealth had been divided up between the rest, would the country be any better off? Haffajee shows that even if the wealth owned by whites had been directly redistributed to the poor, it’d hardly make a dent in the poverty of the bulk of the population. Only 8% of South Africans are white. The new black middle class also accounts for 8% – a number that, says Haffajee, has to triple if we are to reach any of our economic goals and create “inclusive growth”.

In this, Haffajee (she says she’s a social democrat) and her interlocutors begin to get to the nub. Complaining about social racism is one thing, and the experiences of people who have felt the brunt of it are of course deeply meaningful, but the real long-term issue is structural racism: the way apartheid condemned the population, by race, to stick within its constructed class boundaries. Black people would forever be working class, whites would be the bourgeoisie and the rulers.

It may have been useful for Haffajee et al to make a distinction between social and structural racism earlier on in the book, because treating them as one thing is to confuse base and superstructure, making it harder to disentangle causes and effects. But by the latter pages of the book Haffajee is adducing infographics and graphs to explain this, and she’s very good with economics for relative beginners.

She’s given to “Oprah” moments a little too readily for me, but many readers will find her approach a useful and even heart-warming way to reopen and reformulate the conversation about race and power, and to ask, as we have to do repeatedly: Where to from here?