Fighting talk: Nomgcobo Jiba

It has been an eventful 12 months for debates about diversity and transformation, as well as for science, with interesting, quirky and downright strange intersections between the two.

Transformation

For decades, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – and science in South Africa in general – was the preserve and bastion of white men. But the researcher base of the council, which celebrated its 70th birthday this year, is now more than half black and more than a third female.

This level of transformation unfortunately remains the exception rather than the rule. At a conference for women in Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths), the National Research Foundation’s Beverley Damonse said that black women represent just 18% of researchers. This is despite the fact that black women are the largest demographic group in South Africa.

Women represent about 52% of the population in South Africa, but only hold 42% of research positions. That number is lower in Stem fields.

“To exclude women from science and technology or to limit their research development in any number of ways [whether consciously or unconsciously] is to deprive our country of 52% of its potential for innovation,” Damonse said.

Although race transformation in higher education institutions and research councils is having some success, that is not the case for women, particularly black women.

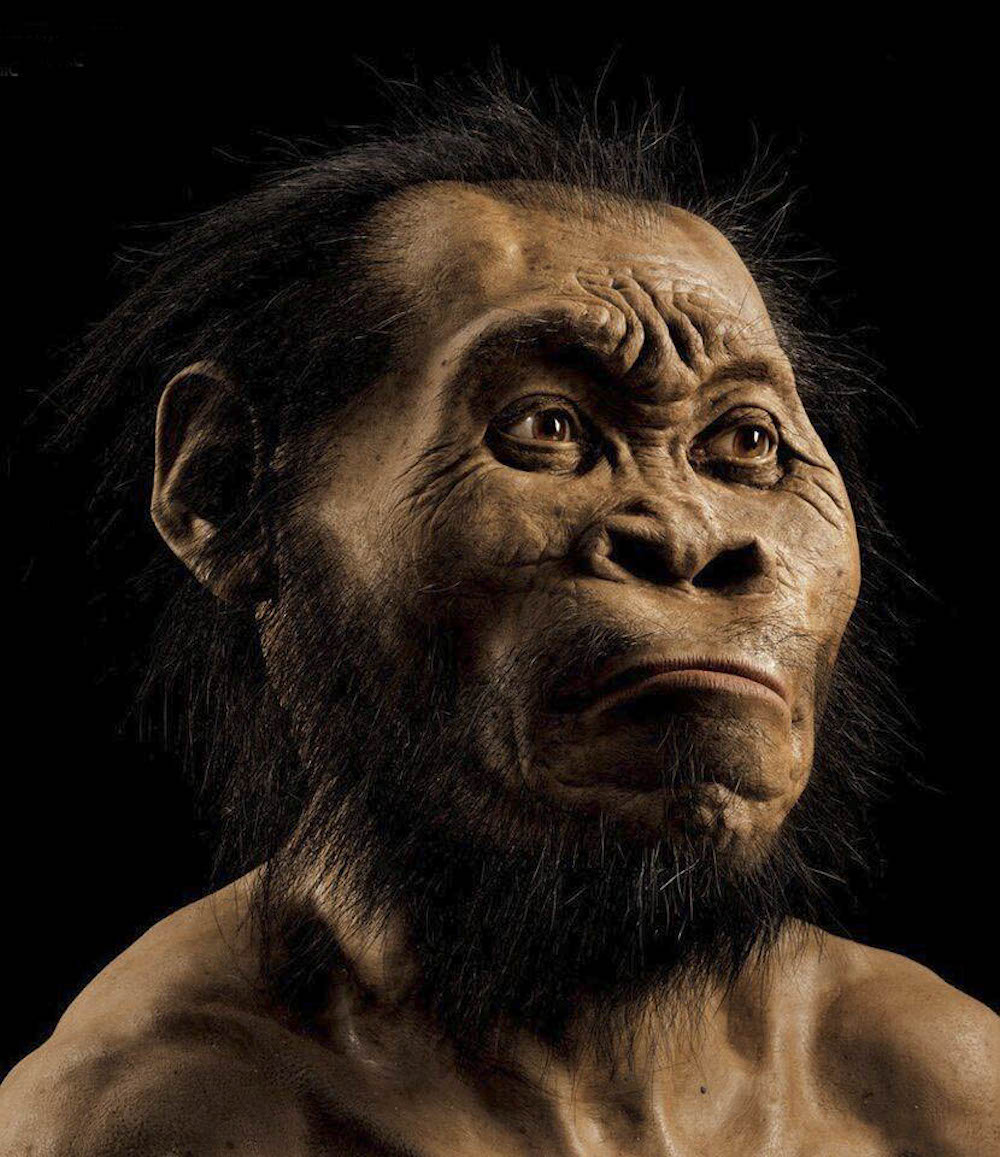

Homo naledi

It is perhaps the most remarkable hominid fossil find in Southern Africa. It is almost certainly the largest haul. Excavated as part of the Rising Star Expedition in 2013, led by University of the Witwatersrand professor Lee Berger, the Dinaledi cave in the Cradle of Humankind yielded up 15 skeletons.

The researchers claimed that the hominins, named Homo naledi, represent a new species and an ancient human ancestor. But the announcement in September was met with mixed reactions: scientists across the world were suspicious of whether Homo naledi was actually a new species and questioned the researchers’ hypothesis that the bones were deliberately disposed of or buried there.

Without a date stamp attached to the collection of remains in the chamber, questions will continue to hang over the find.

The discovery of Homo naledi also sparked a surprise race row. Zwelinzima Vavi, former general secretary of union federation Cosatu, tweeted: “I am no grandchild of any ape, monkey or baboon – finish en klaar. Now prove to me scientifically that I am.” He also tweeted: “I [have] been also called a baboon all my life, so did my father and his fathers.”

These sentiments were shared by ANC MP Mathole Motshekga, husband of Education Minister Angie Motshekga, who told eNCA the hominin fossil find “supports the theory that we are subhuman. That’s why Africans aren’t respected by the rest of the world.”

It underpinned the Western theory that “[Africans] are subhumans who developed from the animal kingdom. Therefore, they [the West] gave us the title of subhuman beings to justify slavery and colonialism,” he told the news channel.

It caught the attention of British biologist Richard Dawkins, who said the negative response “breathes new life into paranoia. Whole point is we’re all African apes.”

Strange but true: Homo naledi was discovered at the Cradle of Humankind. (National Geographic)

Climate change

It was both a good year and a bad year for the Earth’s climate, depending on how you look at it. On the plus side, negotiators achieved a landmark agreement in Paris at the United Nations climate talks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (although countries still have to ratify it).

But this was, in part, because of the depressing climate data that came out in 2015. The United Kingdom’s Met Office, which collects weather and climate change data, found that global temperatures had already increased by one degree above preindustrial levels. Two degrees is considered the “maximum allowable warning” to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change, and the planet is halfway there.

The UK data was complemented by data from the United States’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which found that July 2015 was the hottest month on Earth since records began in 1880. The hottest recorded year was 2014, but 2015 is on track to break that record. Although the data paints a worrying picture, the Paris accords do offer a glimmer of hope – if countries take action.

Autonomous weapons

It is the basis of many movies and a number of science-fiction books: the machine apocalypse, in which scientists and engineers create autonomous machines whose sole purpose is to kill people. But this future is closer than many of us dare to dread.

In fact, this year more than 20 000 people – including big names in science and technology – have signed a petition aimed at stopping a global technological arms race. Signatories to the Autonomous Weapons: An Open Letter from AI & Robotics Researchers petition include SpaceX founder Elon Musk, Nobel prize-winning physicist Stephen Hawking and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

The letter reads: “Autonomous weapons select and engage targets without human intervention. They might include, for example, armed quadcopters that can search for and eliminate people meeting certain predefined criteria … Artificial intelligence [AI] technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems is – practically if not legally – feasible within years, not decades, and the stakes are high: autonomous weapons have been described as the third revolution in warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear arms.”

There is historical precedent showing that nations can pre-emptively stop this technological arms race: in 1998 the UN banned blinding laser weapons. Even though this technology exists, it is not used in warfare. We can only hope governments will feel the same revulsion towards autonomous weapons.

African sexual diversity

It didn’t make international headlines. It didn’t even reach many news agendas at home. But the African Sexual Diversity report, prepared by the Academy of Science of South Africa, was a great response by the continent’s scientists to the oppression of sexual diversity. “We wanted a rational approach to this very irrational response to gender and sexual diversity,” Medical Research Council head Dr Glenda Gray said.

“[The aim] was to unequivocally make the statement that gender and sexual diversity [are] a normal variant of life. We realised that it has to come from Africa and African scientists have to be involved in it, otherwise it will be rejected as something from the ‘West’.”

The 13 experts were asked to answer whether sexual diversity was “un-African”, if it can be “corrected”, whether children are at risk from association with homosexuals and if there are benefits to outlawing same-sex sexual acts, among other questions.

The experts, who included anthropologists, ethicists, geneticists, medical doctors, and public health and mental health specialists, found that there was nothing unnatural or “un-African” about homosexuality.

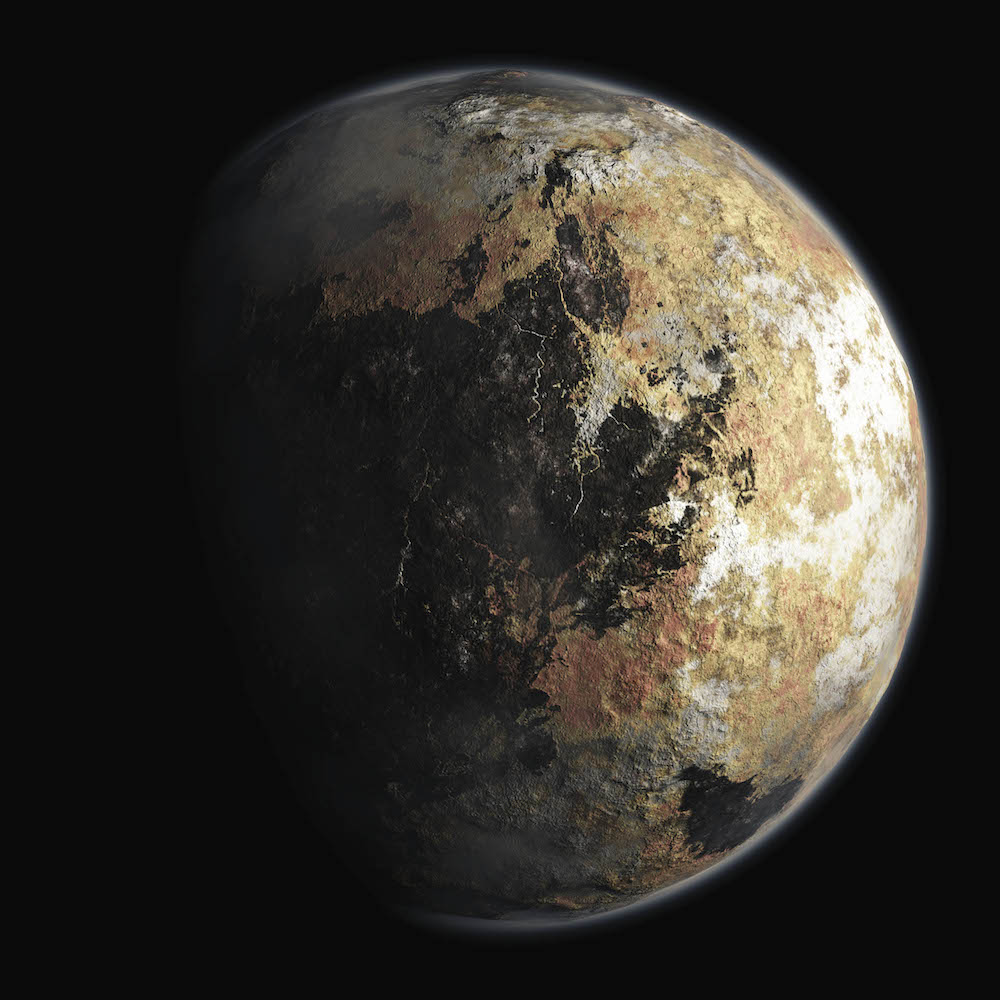

Strange but true: The first detailed images of Pluto were recorded. (Mark Thiessen)

Mars

While South Africa was talking decolonisation, Nasa was dreaming about colonising Mars. It is humanity’s most practical Plan B: move to Mars. This year was an exciting one for our understanding of, and plans for, the Red Planet.

Nasa announced the possibility of liquid water on Mars. Liquid water is necessary for life as we know it, and its discovery on Mars adds to the evidence that the Red Planet could support life.

“Our quest on Mars has been to ‘follow the water’ in our search for life in the universe, and now we have convincing science that validates what we’ve long suspected,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of Nasa’s space mission directorate. “This is a significant development, as it appears to confirm that water – albeit briny – is flowing today on the surface of Mars.”

Nasa’s evidence resides in the intermittent dark streaks on the planet’s surface, smudges running down gullies and canyons.

Using instruments on board Nasa’s Mars reconnaissance orbiter, which has been orbiting the planet since 2006, scientists detected hydrated minerals in these streaks. These substances form when minerals combine with water.

We’ve long known that Mars had water on it but in the form of ice, rather than liquid water, or ancient water that once upon a time moulded the face of Mars. But now we’re talking about liquid water on present-day Mars.

Although this is exciting in terms of our understanding of the planet (and the hopes that humanity could one day live there), it is also a shot in the arm for Nasa and adds weight to the administration’s justifications for its expensive Mars programme.

Pluto

It has taken more than nine years and nearly five billion kilometres for Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft to reach the edges of our solar system, but in 2015 it finally saw Pluto – and so did we. It was the last major unobserved celestial body in our solar system and up until the New Horizons flyby, we only knew it as a blurry circle.

Nasa is still releasing incredibly detailed images of Pluto’s scarred and pitted surface.

Named after the Greek god of the underworld by a 10-year-old school girl, Pluto has been the underdog of the solar system, with its planetary status up for discussion. These images will help scientists understand everyone’s favourite planet that’s not a planet.