Two remarkable events took place in the South African art world of 1989. The first was Albie Sachs’s presentation of a paper titled Preparing Ourselves for Freedom at an ANC seminar on culture in Stockholm. The second was the publication of the book Resistance Art in South Africa, edited by Sue Williamson.

Sachs’s text, controversial at the time, has since become justifiably legendary because the author, as one of the most visible white South Africans in the leadership of the ANC, believed that, with the dawn of freedom so near, art had to recalibrate its relationship with political doctrine and rethink its own necessity.

His argument was that, once apartheid ended, contemporary South African art should chart a new direction and cease to be the instrument of a struggle that had successfully run its course.

Rather than holding on to the functional imperative of 1980s art, it should recover the lost values of ambiguity, complexity and beauty for its own sake. Artistic imagination, said Sachs, now needed to be called up to counter apartheid’s ugliness, by making the world anew.

Williamson’s book was a survey of work done over the previous decade. There are enough examples in it to appreciate why Sachs saw an urgent need for change. Two years previously, in 1987, there had been a Culture in Another South Africa conference in Amsterdam, where participants had ramped up the call for the international cultural boycott of the apartheid state, and for a more engaged contemporary art scene.

And yet Williamson’s book shows us that, for the many works that confront directly the racist and oppressive machinery of apartheid, there are others that offer more complicated views of both the human condition and the dramatic formal gesture.

Though Paul Stopforth’s plaster sculpture George Botha (1977) and Manfred Zylla’s participatory Before and After drawings (1982) set the tone of hard-hitting resistance art, others are indicative of the vastly different range of thematic and stylistic preoccupations of artists presented in Williamson’s survey: Johannes Maswanganyi’s funny, frank wood portraits of white and black leaders, for example, or Andries Botha’s enigmatic woven sculptures.

Given its title, one might mistake Resistance Art in South Africa for a collection of work produced in response to the Amsterdam declaration or, before that, to the resolutions of the Culture and Resistance festival in Botswana in 1982: that is, the very kind of work that Sachs declared unwelcome in a soon-to-be- free South Africa.

Yet the book is as much an account of resistance art in the 1980s as it is Williamson’s manifesto for an expanded horizon of formal possibilities within late 20th-century South African art. It is, moreover, and crucially, a testimony to Williamson’s understanding of the artistic life as an imaginative journey propelled by an ethical imperative and faith in art’s signifying power.

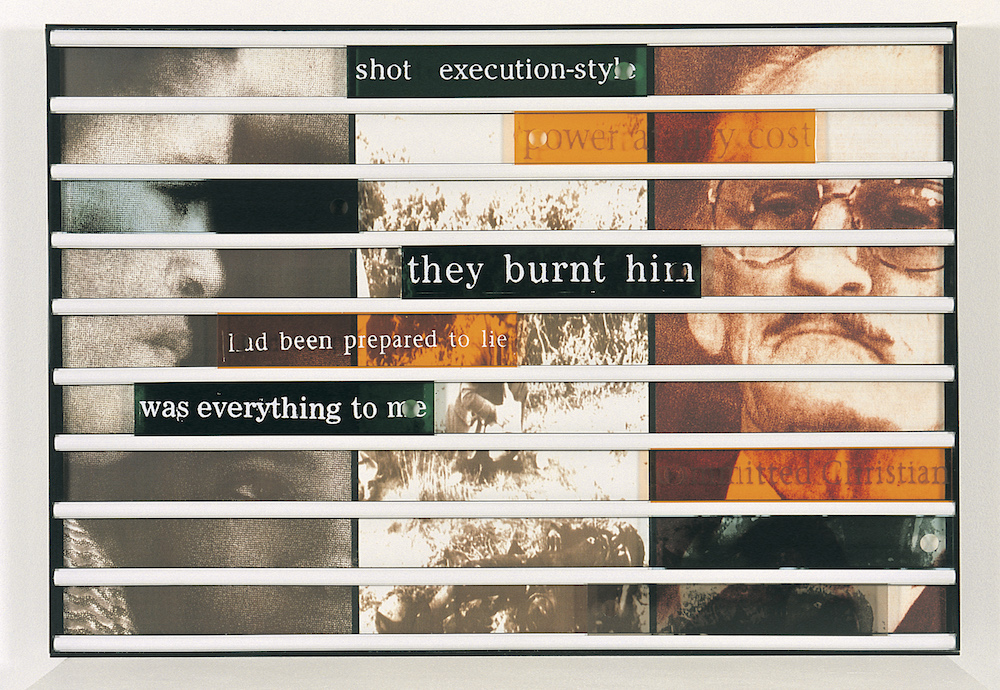

Sue Williamson’s work extended the meaning and imaginative possibilities of the “culture as a weapon of struggle” mandate. (Supplied)

The call for art to participate in the work of progressive social and political movements relies on a fundamental perception of the work of artists as much more than the production of things that justify themselves solely by their formal affect and aesthetic condition. If the primary task of the anti-apartheid movement was the attainment of a better society shorn of the terrors of a morally bankrupt regime, then artists who shared in this conviction imagined their works as valuable principally to the extent that they were ethical gestures: catalysts for the common good.

Clearly, this contradicts and rejects the 20th-century modernist preoccupation with the implication of Immanuel Kant’s notion of aesthetic autonomy: the understanding of aesthetic experience as self-referential, without any value beyond itself.

We might call this countertrend “aesth-ethics”: a fundamental and synergistic fusion of aesthetics and ethics that reflects the widespread African (and equally worldwide) insistence on the pursuit of the beautiful (aesthetics) and the good (ethics) as a unitary endeavour.

This can be best illustrated in the Igbo word and idea mma, which simultaneously means beautiful/pretty and good in the ethical sense. Thus, although the desire to seek sensorial beauty (ich mma) implies a preoccupation with physical appearance and optical impression, to be good (idi mma) also connotes the condition of being good and beautiful.

Behind this lexical conflation and philosophical layering, I want to suggest, is the same principle that has always driven those artists who see their work as expressive acts tasked with examining, prognosticating, commenting or meditating on the human condition, all in the hope that such gestures can contribute in some meaningful way to the making, or at the very least the imagining, of a better world.

Such contemporary artists would include Obiora Udechukwu in Nigeria, Ibrahim el-Salahi in Sudan, Inji Efflatoun in Egypt, Mozambique’s Malangatana Ngwenya and, beyond Africa, artists such as Leon Golub, Dread Scott and Hans Haacke.

This simultaneous engagement with aesthetics and ethics has, in fact, given us some of the most profound reasons why contemporary art matters; why art in the hands of artists of substance attains both dimensions of mma – the aesthetic and the ethical – as it reaches for full elaboration.

Williamson is one such artist, and this idea of “aesth-ethics” is crucial to an understanding of her work. She has, from the beginning of her career, assiduously sought the most compelling formal language with which to articulate and express ideas that in many ways exposed the moral bankruptcy of apartheid political culture and racist ideology.

This has earned her a place at the leading edge of contemporary South African art. Compared to her contemporaries, she is a master of subtle outrage: her work simultaneously excites us for its exploration of medium and process, and moves us to contemplate the meaning of community, citizenship and subjectivity in South Africa and other societies scarred by extreme imbalances of power.

The idea of “aesth-ethics” is crucial to an understanding of Sue Williamson’s work. (Supplied)

This is evident in the series of works for which she gained early critical attention in apartheid-era South Africa; works that, although they were included in Resistance Art in South Africa, stretched the horizons of “resistance art”, invariably extending the meaning and imaginative possibilities of the “culture as a weapon of struggle” mandate.

Consider, for instance, the structural ordinariness and conceptual power of her first major work, The Last Supper (1981), a gallery installation of rubble gathered from the demolition sites of Cape Town’s District Six and surrounded by six chairs draped in white borrowed from Manley Villa, the Ebrahim family home that had been marked for destruction as part of the racist government’s promulgation of its Group Areas Act.

Three photographs on the wall of the Gowlett Gallery showed the Ebrahims celebrating Eid in their home. At a time when South African photographers and journalists testified to apartheid’s systemic violence by depicting District Six homes turned to rubble or the traumatised inhabitants menaced by demolition crews – powerful testimonials, no doubt – Williamson chose instead to show a family celebrating in the shadow of eviction and the impending destruction of their home.

In a major work that memorialised the crumbling of apartheid’s walls, For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990), she colour-copied and displayed, in 49 artist-designed frames, the complete pages of a black man’s passbook, perhaps the most infamous document produced by apartheid. In these landmarks of anti-apartheid art, she used the photographic image or politically charged document to insist on the dignity, substance and courage of both the oppressed coloured and black South Africans and their white allies.

Williamson has continued to explore, untangle and lay bare moral knots and ethical complexes in today’s world, just as she did during the decade of “resistance art”.

This clearly suggests that she did not quite heed Sachs’s call for a radical change in post-apartheid art. She did not believe, I suggest, that the work of engaged contemporary art was, or is ever, done simply because a particular political ideology and system had expired in her homeland and in the human society.

In any case, if Williamson did respond to Sachs’s call in 1989, it took the form of reimagining her community as the human family, not just the post-apartheid South African world still scarred by its traumatic past and new challenges.

This is an edited extract from Sue Williamson: Life and Work, edited by Mark Gevisser and published by Skira Editore. Williamson’s show The Past Lies Ahead, which includes older work among her newer output, is on at the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town until March 2.