Seven years ago my sister Sandy phoned me to say my father was dying and I had better fly down super-pronto from Johannesburg to Somerset West if I wanted to say my final farewells. Acquiescing to her desire was one of the better decisions I ever made. I not only bid my father adieu, but also – since he was only able to listen and unable to respond – I unloaded upon him the 40-odd years of my life’s sins I hadn’t previously divulged, and believe me, there were plenty.

As my father had had Alzheimer’s for several years it all probably went in one ear and straight out the other. He was also dying of cancer and only on palliative care, because the medical establishment he was spending his final days in had, together with Sandy, elected to take him off his medication to hasten his demise. He could no longer eat, so he was dying of starvation and thirst.

Consequently, as I cleared my conscience in a sort of one-sided, three-day confession (had he been able to talk, I’m sure he would have begged me to stop) he writhed in discomfort, contorting to such an extent that he almost sat upright at times and ended up in nigh-impossible backbends. It all left me wondering why the doctors were unable or unwilling to administer a merciful coup de grace. I was at times tempted to put him out of his agony with a pillow, like Chief Bromden did in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but I ended up just chanting mantras. I didn’t know what else to do.

By contrast, my dad’s dog, which outlived him by many years, was dispatched with utmost grace, passing painlessly away while surrounded by its loving family and in mid-chew through its favourite delicacy.

Sandy, who was present at the death of both of my parents, and those of her husband, says: “It’s hard to understand that even if you sign up for not dragging things out (a Living Will), if you are not of sane mind, you (the family, and the doctors present) cannot implement it. Not one of the four parents was of sound mind at the time that this decision would have needed to be made.”

The frail care where my father died wasn’t breaking any law by withholding his life-supporting medicines and nutrition. While South African laws allow life-sustaining treatment to be withdrawn to cause death, it prohibits euthenasia, though both ultimately result in the death of the patient. Why one is okay and the other is not — and the difference can mean dying with dignity or most certainly not — is now being disputed in our courts, as it is, increasingly so, across the world.

Human euthanasia (an outside party, usually a physician, performs the final action such as administering a lethal dose) is legal in only five countries, and assisted suicide (where the patient takes the final action themselves) is legal in another five countries and five American states.

The more I looked into how the law across the world protects at all costs the right to life and living with dignity — but not dying with it — the more I realised that it’s a crazy, contradictory legal minefield I was stepping into. For instance, you might go to prison for 14 years if you help someone die in England, though suicide itself was decriminalised back in 1961 (if you’re wondering how you may get punished for committing suicide, remember you may fail in your attempt). As Derek Humphrey points out on DignitySA’s website: “Thus it is a crime to assist in a non-crime.”

One may also ask how, in South Africa, with one of the most progressive constitutions in the world, permits termination of pregnancy, but not assisted suicide. A young mother’s chances of raising a healthy, productive child may be slim, but a terminally ill person’s chances of recovery and of quality living are nil.

Preventing a person from dying even if they actively crave this because of great suffering appears to be something our legal system inherited from the Middle Ages. Pathologist Jack Kevorkian, who in the 1990s assisted more than 100 people to die with dignity, made this point by appearing in one of his numerous court cases dressed in medieval clothes and with a pillory fastened around his neck. He likened starving a terminally ill patient to death instead of administering a rapid, painless way out to something only the Nazis would have advocated. Kevorkian was jailed for euthenasia and served eight years of a 10- to 25-year sentence.

In April last year Cape Town advocate Robin Stransham-Ford applied for the legal right to assisted suicide because he was suffering from terminal prostate cancer and his disease and medication was causing him great pain and distress. He wanted to die awake and aware with his friends and family around him, and asked the courts that the doctor who administered the fatal dose be protected from criminal sanction. Stransham-Ford won his court order in May but died two hours before it was granted. Judge Hans Fabricius, however, refused an application by the government and the Health Professionals Council to rescind his order, saying that it could affect other parties and that Parliament and the Constitutional Court should reconsider legalising assisted suicide. Fabricius was outspoken on the matter: “The irony is, they say, that we are told from childhood to take responsibility for our lives, but when faced with death we are told we may not be responsible for our own passing.”

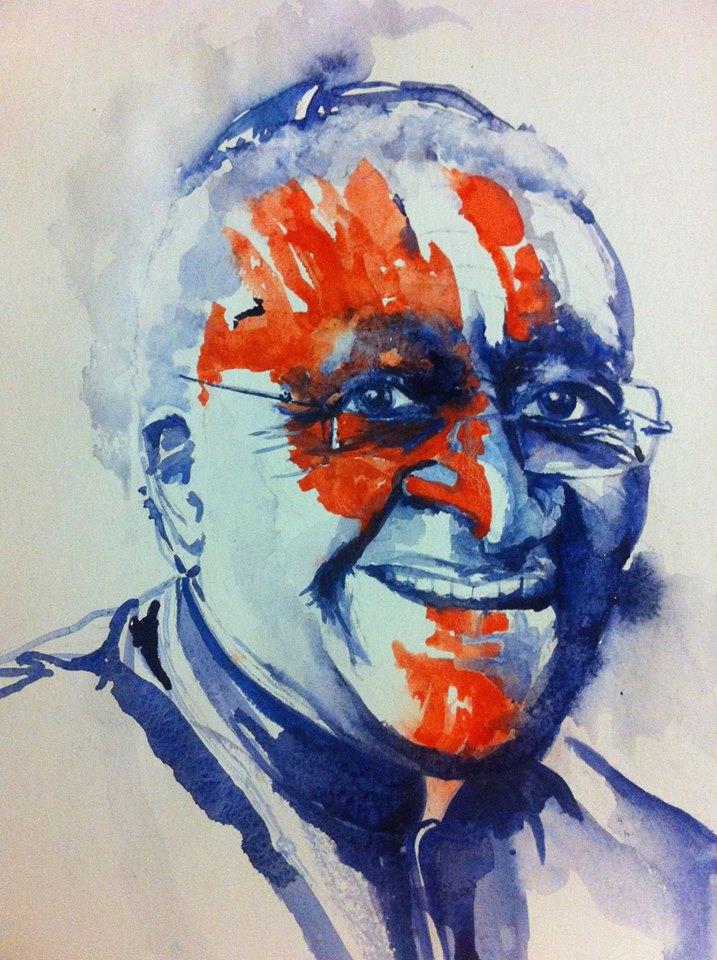

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu has long been an advocate for the legalisation of assisted suicide.

(Artwork by Lioda Conrad)

The issue will appear before the Supreme Court of Appeal later this year, but this does not mean it is easy now to apply for a legal assisted suicide, says the former chief executive of the Ethics Institute of South Africa, DignitySA’s Professor Willem Landman.

“Everyone is holding fire, pending the appeal. It is costly and cumbersome. Costly, because one has to get attorneys and advocates to represent one; cumbersome, because of the documentation, affidavits [and so on] required.” One can approach the Bench on the basis of precedent, he says, but “it has to be case-by-case, until such time as the law has changed”.

Lee Last of DignitySA says: “DignitySA’s legal team will not be taking on any further matters until the Stransham-Ford case has been settled, but this is not to say that there are not people who, at this very moment, are considering going the legal route. On the contrary, we receive calls weekly from people wanting to end their suffering.”

Battle lines are being drawn in the matter between the minister of justice and correctional services and the estate of the late Stransham-Ford. Friends of the court are joining both sides: Doctors for Life and Cause for Justice, among others, will assist the State; the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (Cals) and DignitySA will aid the respondent (Stransham-Ford’s estate). Heads of arguments must be submitted soon.

Landman says the appellants are likely to advance several arguments against assisted dying, including that Fabricius’s judgment encroached into the domain of the legislature, and that if assisted dying is made legal that law will be abused: there will be insufficient safeguards, and the state will be unable to regulate it.

“We have heard a few days ago that Hospice has withdrawn as a friend of the court [for the State]. We are puzzled since it is anticipated that one of the main arguments of the state is that adequate palliative care would make assisted dying redundant,” says Landman.

“Palliative care and assisted dying are emphatically not mutually exclusive. No one argues against the best palliative care but, for some, unfortunately it is not enough and does not help with intractable and unbearable suffering. And they may choose not to die unconscious through ‘palliative sedation’. They consider that contrary to their free choice and their dignity. Cals would argue that it could be considered to be torture.

“One question for Hospice (and the justice minister) is: have you asked what the Constitution asks of us? That is the key point. And if you don’t agree, don’t practice assisted dying. No one forces you to, but let others follow their conscience as the Constitution allows, as we (Dignity SA) and the majority of constitutional lawyers and professors in SA believe.”

Lee Last of DignitySA says that despite the fact that their legal team is working pro bono, “disbursements are mounting, and are expected to reach six figures”. To this end, and to honour those who have dedicated themselves to changing an unjust law, DignitySA will host its first fundraising auction Life Imitates Art at S Art Gallery, on the corner of Victoria Avenue and Oxford Street in Hout Bay, on March 12. Many of South Africa’s most notable artists such as Benon Lutaaya, Lioda Conrad and Casper de Vries, as well as several child artists, have donated to a cause they feel strongly about.

For more information, visit dignitysa.org.