The Compassionate Englishwoman zooms in on the Boer war by telling the life story of Emily Hobhouse.

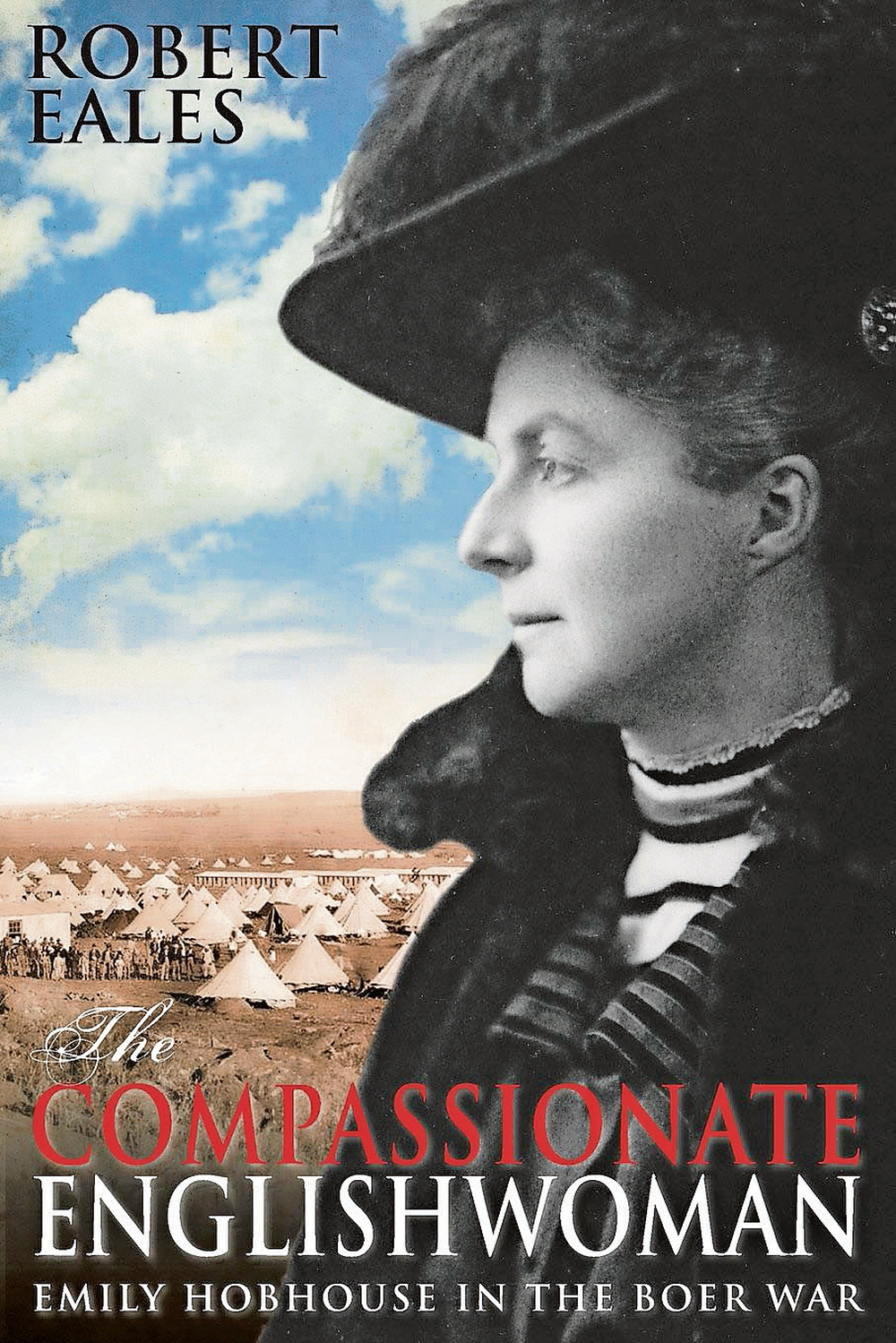

THE COMPASSIONATE ENGLISHWOMAN: EMILY HOBHOUSE IN THE BOER WAR by Robert Eales (UCT Press)

It is of interest to see this book published by UCT Press at a time when the British Empire and its celebrated and reviled proponent, Cecil John Rhodes, are so hotly debated, in the year that his statue was removed from the University of Cape Town’s campus. As progress is made in decolonising knowledge and syllabi, inter alia, one wonders if it would be published now, a year later.

The Compassionate Englishwoman was first published in Australia by Middle Harbour Press. The author was raised in Bloemfontein, is now in Sydney, and this book is a post-retirement project, intended as a popular account and not an academic text.

It may also be intended to show that not all English people were supporters of the empire, and that there were a few brave souls who tried to counter the prevailing spirit of conquest and colonisation. This argument, that “not all whites” or “not all English people” have erred, has carried little weight with those who see it as confirming and condoning the ignorance of white privilege that has followed colonisation.

Emily Hobhouse, too, may have been blind to the depth of white privilege, though her intentions were benevolent with regard to the concentration camps for white people.

She made it her business to help the most innocent victims of the British scorched earth military reprisals taken against civilians, the women and children who were driven into the camps. Her story is one of courage and independence for that era, and Eales shares the respect and gratitude the Boers showed her. She took a railway truck of supplies into the war zone and she lived rough on the trains despite her aristocratic birth.

Eales does well on behalf of women in history insofar as he corrects the view of her as meddling and hysterical, a view assiduously put out by those, mainly men, who did not wish to hear her damning reports of what the British concentration camps were like. He writes of how she took this information back to England and worked to spread it, with the help of the Quakers and some opposition parliamentarians. It exposed the role of the conservative press, The Times, in spreading misinformation.

Oxford University then, as now with #RhodesMustFall in Oxford, offered a space for open debate and Hobhouse was able to speak there, with the support of the Master of Balliol College, Edward Caird.

A more recent commentator on this war was Rashaka Ratshitanga, Venda poet, activist and political leader, in the 1985 documentary The Two Rivers, in which he says: “The Boer war, as it came to be known, was like two dogs fighting over a piece of stolen meat.”

Eales does address this briefly in a careful statement that “the Boer republics belonged to no one but the people who lived in them”.

Eales’s book is detailed and persuasive as far as it goes, and refers to the work of local historians, JC Otto, Bill Nasson and Elizabeth van Heyningen, and Peter Warwick, who wrote specifically about black people in that war, as well as much primary material. His focus, like Hobhouse’s, was on the camps for white people.

He is consistently severe in condemning the callous brutality and passing of the buck of Roberts, Kitchener, Milner and others. His criticism of Hobhouse is to note that she did not visit the camps for black people. He says: “One can only speculate why this is so. But it troubled her.”

This led to her suggesting, in Bloemfontein, that women loyal to the Cape Colony and England should visit camps for black people because “the blacks were, after all, supposed to be neutral in this conflict”.

The camps for black people are again discussed later in the book when two were visited by the English Ladies’ Committee.

At the end of the book, Eales has included maps from the Anglo Boer War Museum which show 47 concentration camps for white people and 65 for black people. Camp commanders were obliged to write up reports and these show more than 42 000 recorded deaths, of which 27 927 were white people and 14 154 were black people – and most of these were children.

The scope of Eales’s biography is clear. A complete account of this great tragedy remains to be provided, especially on the fate of those over whose ancestral homes the war was being fought: the Sotho, Griqua, Tswana, Venda, Tsonga, Shangaan, Pedi and Ndebele.