Joe Mamasela is arguably South Africa’s most notorious askari – a once-loyal member of the ANC who changed sides in the fight against apartheid and became an efficient killing machine for the security police.

Once part of the Vlakplaas death squad, Mamasela admits that he and his colleagues killed “30 to 35” anti-apartheid activists during the 1980s. The unit would often drug their victims before killing them, and frequently disposed of their bodies by burning them or blowing them up.

Now in his 60s, Mamasela runs a business training security personnel and bodyguards. Many of them end up working for the ANC. He lectures these trainees in a small room modelled like an amphitheatre. Pink dolls lie on the floor – plastic representations of human victims of some vague, potential disaster.

A dismembered plastic foot, painted red with fake blood, glistens on a table. Inside Mamasela’s office, shelves are laden with plastic red fire engines. A huge painting of a helicopter hangs on the wall.

Mamasela appears prosperous, and cheerful. I am a fraction of his age, but he calls me “ma’am”. I expected shame or sorrow, but he radiates something else, something far harder to describe or understand: a kind of terrible survival. His life is sodden with myriad terrible deaths.

The acts Mamasela has admitted participating in are horrific.

“Are you haunted?” I ask him. His answer is a quick and certain no.

“You know, haunted is when you know you have done evil, willingly and wilfully – it’ll haunt you. But if you know I was subjected against my will, against my political will, against my religious convictions, to do these things – and I was forced and I did the only honourable thing left for me to do, which was to come out and tell the truth and help the families to get closure, which I did. I think therein lies my survival skills. My Christian convictions helped me a lot.”

No amnesty

Mamasela chose not to apply to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for amnesty for the murders he helped to commit, but did testify about them – in often gory detail. He was not prosecuted for a single one of these murders. He maintains that this was because he told the truth.

“In the TRC, you go and you lie, you get your amnesty … I never asked for amnesty from the TRC because I knew what I was doing and why I was doing what I was doing. And I know the policies of the African National Congress and I said to them: Anyone who thinks I still owe them anything, let them challenge me in a court of law. And then let’s unravel what went wrong where.”

During my two-hour interview with Mamasela, he becomes tearful only once: when he reveals how a teacher at his primary school paid his R2 school fees for him – after he robbed another child of the money on his way back from buying fish and chips for the same teacher.

He was in standard three at the time, he tells me.

“I saw a young, little misguided youth next to me, dangling the two rands. I didn’t see the two rands, I saw my school fees … I grabbed the money and I ran. Little did I understand at that stage that I was wearing my school uniform, which was a clear giveaway.”

After an hour, during which Mamasela says his young self proudly handed over the R2 “with a big smile” to pay for his school fees, the boy he had robbed arrived at his classroom with his mother. The child immediately pointed out Mamasela as his assailant.

“The teacher could see that I stole to get education, to buy education.”

‘Informed decision’

It is at this point that Mamasela appears overwhelmed, and clasps his hands in front of him, almost as though he is praying.

“This is painful,” he says, “I’m sorry.” Then he adds: “The teacher paid the fees for me, on my behalf.”

He regains his composure and continues: “Then I made an informed decision that, no, my life cannot go on like this. Either I become a full-time criminal and I go and kill whites in their houses, or I join the revolution structures.”

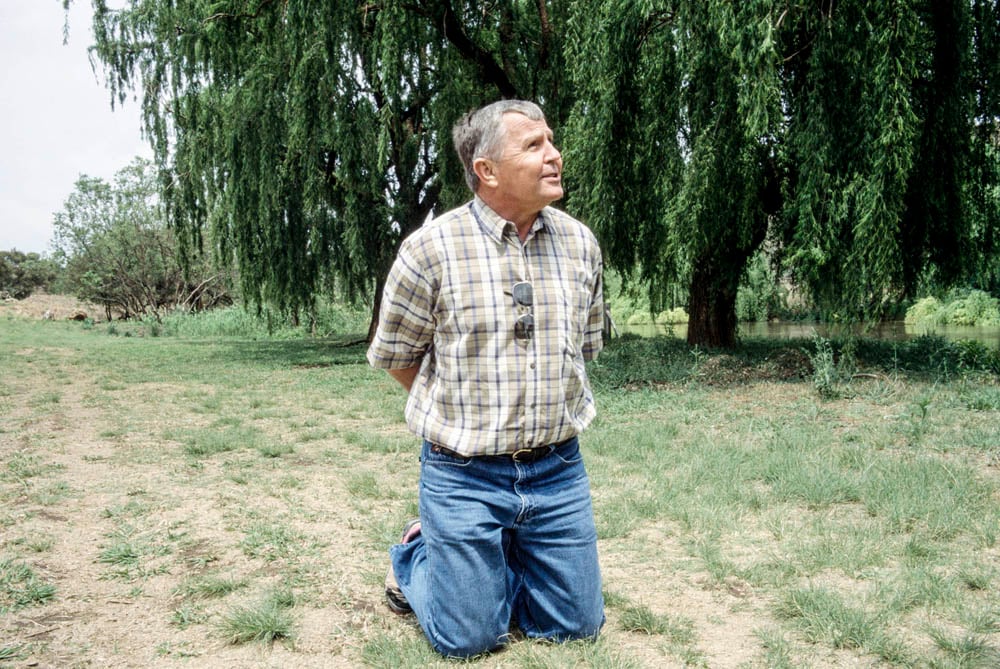

Dirk Coetzee – demonstrating here how Mamasela interrogated prisoners at Vlakplaas – described the former askari as a psychopath, a description Mamasela has angrily denied. (David Goldblatt)

Mamasela becomes animated as he talks of his exposure to black consciousness, the writings of Malcolm X and the “Hegelian” theory of dialectical materialism.

He can quote large reams of the writings of Karl Marx, and the ANC’s Freedom Charter.

He describes blowing up the Moroka police station as part of an ANC operation and stresses that he and his unit were at pains to ensure that no one was killed.

“I was a loyal, loyal cadre of the ANC,” he says. “I was ready to die for the revolution.”

So how did this passionate advocate of revolution end up becoming one of its deadliest enemies?

Two accounts

There are two accounts of the “turning” of Mamasela.

Some reports claim he became a police informant, after he was arrested for theft and burglary in 1979. But he says he decided to join the ANC in 1977 and became a dedicated intelligence operative, posing as a priest to transport bombs.

He says it was the party that betrayed him two years later – and set him up to be arrested by the security police.

According to Mamasela, he was stripped naked, tortured with electrodes and beaten.

“You know what [hurt] more than the beating was the realisation that my own comrades, my own commanders in the ANC, sold me out on a silver platter. And I became very bitter. I was very bitter. I was extremely bitter. And the ANC policy was that if someone sells you out, you reserve the right to eliminate them.”

So why would the ANC sell you out, I ask. “Jealousy,” he answers. “It plays an important role in the ANC … In the ANC, they kill people for flimsy ideas. If you are suspected of being a sellout, they will kill you.”

He continues in this vein when I ask him why he decided to join the security police.

“A new concept of revolution, a new concept of the enemy became reality in me. Because every time I’m out, it is the white hands that pick me up. Every time the black man pushes me down, it is the white man who pushes me up. Now I ask myself: Who is the real enemy of a black person? They [the security police] said you must be an impimpi [informer] so you can work for us. And I said no, I won’t be an impimpi because they will kill me. I want to join the police so I can go and arrest them and shoot them and kill them for destroying my life.”

Good at grim killing

Mamasela was very good at the grim and dreadful killing that the Vlakplaas unit specialised in. The unit’s former commander, the late Dirk Coetzee, would describe him as a “psychopath”. It’s a description he angrily denies.

It is clear that Mamasela’s narrative of his life is deeply defined by his own sense of victimhood.

Early in our interview, he describes being arrested as a 16-year-old with his father, who had been accused of trespassing.

“To this day I can see the shivering body of my father, how he was scared. The guy who handcuffed him was not more than 19, 20 years old, a white Afrikaner boy. I was pissed off. My father was an adult, he was the head of my household. I held him in high esteem and there he is, shivering, in the face of a small little boy.”

Yet he would later join a group of white police officers who would do far more terrible things to the anti-apartheid activists who crossed their path. The contradictions in Mamasela’s account are manifest and disquieting.

Something slides under his words, his grimaces, his moments of tearfulness and his descriptions of betrayal and violence, punctuated with the word “ma’am”.

Witnessing fear changes the human heart. It may prompt a fight for justice – or it may, sometimes, spark a quest for the ability to create that fear in others.

In the blurriness of a life defined by paranoia and violence, fear may feel like power. But it’s not the same.