Cities make sense: many people in one place can unlock all kinds of creativity and solutions. Things work better on a large scale – more widgets, more innovation, more wealth. Cities are the ultimate expression of human social evolution.

Except cities don’t work as they should. Half the world’s population is crammed in conurbations that need a constant supply of material. Like a dirty blight, they suck in resources and waste them with incredible inefficiency.

If you live in Johannesburg, your electricity comes from coal-fired Eskom power stations 100km away in Mpumalanga. Your water is pumped, using electricity, 400km from Lesotho. And, in all likelihood, the wheat in your bread is from the United States. A quarter of that electricity is lost in transmission. The same goes for water. And a third of food is thrown away.

Conduits are rusted and water pipes are cracked. Rubbish mounds replace mining dumps as the horizon. Sewage flows into rivers. Green areas are paved over. Cars spew out sulphur. And people’s health is affected.

Most cities are unpleasant places in which to live, except for a minority who can afford to insulate themselves.

Poor planning means cities are vulnerable to droughts and floods in the face of climate change.

Yet cities should be harnessing the power of the 3.5-billion people who live in them to make them the nodes of human civilisation.

Some cities are on this path. Smart cities – once a snazzy phrase for a Jetsons-style future – are becoming a reality. With governments failing to take action on climate and environment issues, cities, through initiatives such as the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, are seeding the way.

Transport

Cars make no sense in a city. They take up huge swathes of land just to sit idle. Cities need everything to be as efficient a use of energy and space as possible. That means public transport.

Rich countries use underground trains. South Africa, learning from Brazil, is rolling out a rapid bus system in its major cities. This creates dedicated lanes for buses, which can move more people around quicker. That system is linked to a complete system of public transport: people leave home on a bicycle, pedal along a safe cycling lane, get to the bus or train and then arrive on the other side before they walk the last bit to work. Fewer vehicles. Less pollution. More space for parks.

Sweden is building cycling highways so that people can commute through the driving snow to work. Johannesburg has started rolling out dedicated cycling lanes. China is piloting a system of huge buses that can move hundreds of people at a time. These transport solutions are plugged into a city’s computer network, which works out where new transport routes can be built and where traffic should be sent to spread the load.

Waste

Cities are running out of space to put waste. In Delhi, people live up against rubbish dumps. This is because everything comes into cities in packaging. This is put in a bin, before heading to a landfill. These dumps increase the potential for disease and contain heavy metals. They are also a visual representation of how inefficient society is – food is thrown away.

But waste is a resource and smart cities are waking up to that fact. Old dumps are being used to create electricity. Johannesburg now produces 19 megawatts of capacity from five of its landfills. To stop waste getting to this point, South Africa’s metros are passing bylaws that force people to recycle their waste. Green waste can make biomass. Food can make compost. Everything else can be broken down into its component parts and reused.

Many cities, and big companies such as Unilever, have started ensuring that no waste goes to landfills. Cities in southern Spain have started closing their landfills as a result.

Water

Water is the number one constraint for cities, now and will be increasingly so in a climate-affected future. Most big cities are on rivers but still need to suck water in from the countryside.

Cape Town relies on five big dams to its east for water. This takes water from the countryside, often to the detriment of farmers who need it to provide food for people in cities. And a third of municipal water in South Africa’s cities is lost.

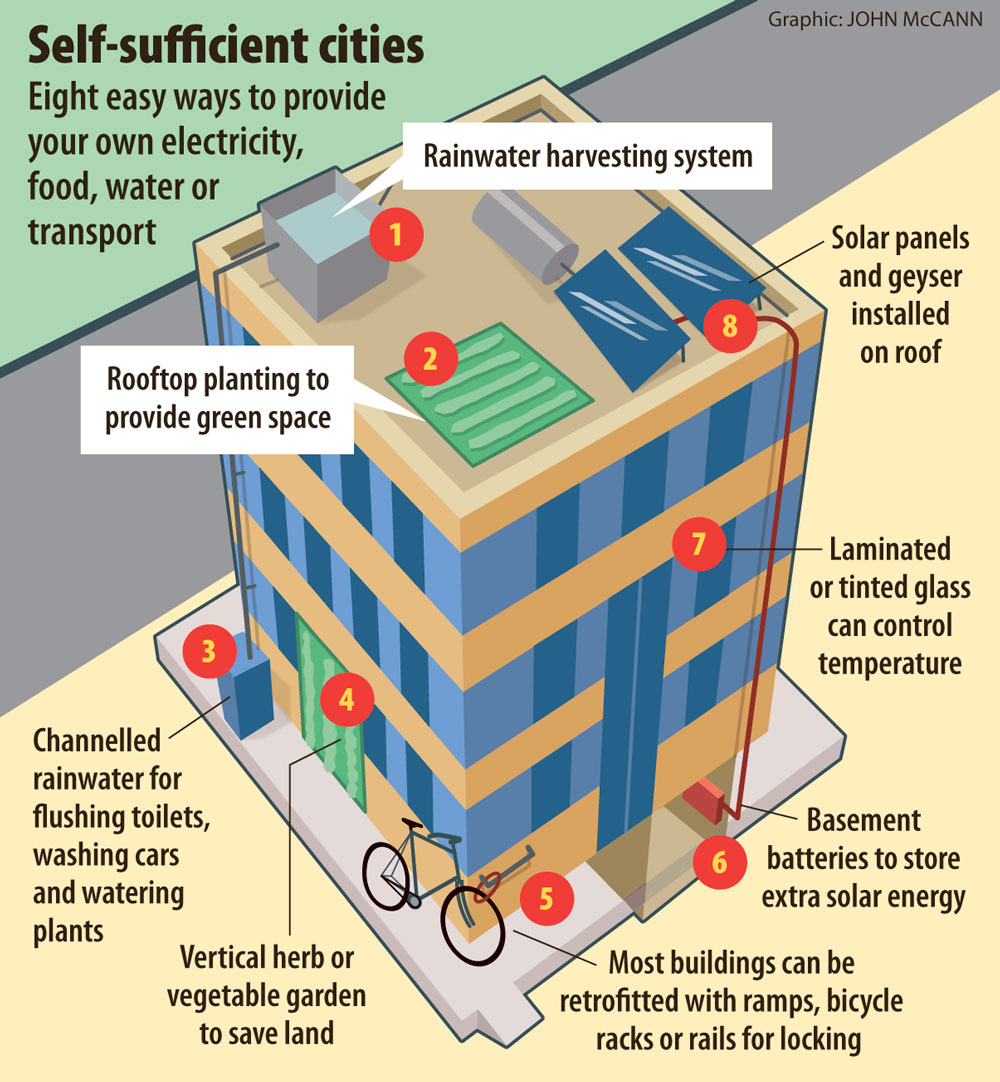

The solution is more efficiency – such as business using less water and in cities harvesting their own. Many cities now have building legislation that requires every roof to catch water. In Windhoek, wastewater from the city is cleaned and recycled into drinking water.

Energy

Cities suck in huge amounts of energy from far-flung places. This is wasted in transmission and in providing power to old buildings and groaning factories. All of that production – and the sheer amount of cement – means cities are hotter than their surroundings. That results in inefficient air conditioners blasting away all day long. The cities of today are breaking power down to the household level – everything must make its own electricity.

In New York, banks of batteries in the basements of buildings now capture solar energy, which is then sold to the neighbourhood. In Lagos, diesel engines ensure supply when the grid fails. In South Africa, building regulations now demand that new homes and offices are energy efficient. That means geysers warming water from the sun, insulated walls keeping the temperature stable, and buildings facing north to suck in more weak winter sun.

New types of renewables are also being rolled out to power these buildings, from solar cells that can be painted on to a wall to wind turbines that spin quietly on a roof. In Holland, cycle lanes generate electricity. Today’s cities are their own generators.

This is part of a series on renewable energy.