COMMENT

The problem of weak learning outcomes in historically disadvantaged sections of the school system, as manifested in the matric exams, resulting in skewed access to post-school education, is perhaps the single biggest marker of unequal opportunity in South Africa today.

The main root of the problem is to be found far earlier than in the secondary schools – the majority of our children are not learning to read for meaning in the early grades. Put differently, the biggest opportunity for addressing the inequalities is through improving the teaching of reading in grades one to three.

Although these problems are not unique to South Africa, there is evidence that some of our neighbouring countries are achieving better reading outcomes with fewer resources. This means that better instructional practices in the classroom can make a difference, besides any resource constraints.

If we’re going to improve our education outcomes, we have to correctly identify the sources of the problem. The government has already recognised this, as demonstrated by the rapid expansion of the grade R programme.

Although the quality of grade R varies considerably between schools, over time it will become an important part of quality improvement in our education.

But the real key to improvement is what happens in the foundation phase (grades one to three). During these critical years, schoolchildren are expected to master the gateway skills that make academic learning possible for their entire educational careers.

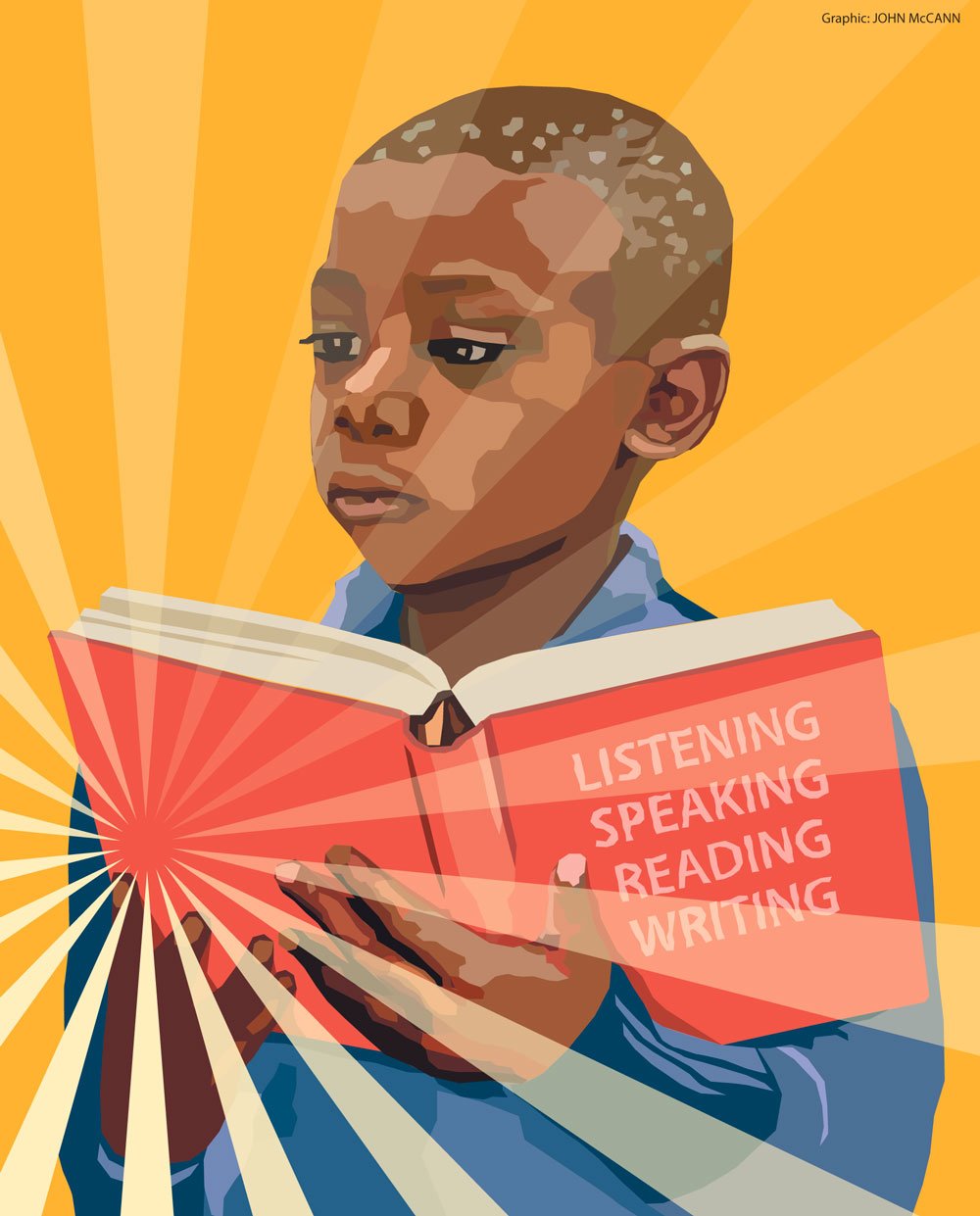

Starting in grade one, classes focus on listening and speaking as well as reading and writing in the children’s home language. Teachers introduce numbers and other basic concepts of mathematics. Schoolchildren get exposed to a basic knowledge of themselves, their community and our world.

But schoolchildren must learn to read so that they can read to learn as they enter the higher rungs of the education system.

For the majority of schoolchildren who do not become fluent readers (both in their home language and English) by the beginning of grade four, the challenges of mastering the required knowledge as the curriculum demands increases and is often insurmountable.

For most schoolchildren, particularly pupils in rural areas and working-class townships, the gap between their learning levels and the demand of the national curriculum gets wider and wider.

So what are the national and provincial departments of education doing about it?

Over the past decade, the department of basic education has introduced three policies that will provide a platform for system improvement.

First, the revision to the national curriculum (Caps) that was introduced half a decade ago was designed to make teachers far more aware of the need to teach all the literacy skills – phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension and writing in the children’s home language and in the language they are likely to continue to learn in grade four.

Second, the department has made high-quality workbooks available to all primary school pupils.

Finally, the introduction of the annual national assessments (Ana) has provided invaluable information about learning outcomes to parents, teachers, schools, district support staff and departmental planners. Because this has been the only standardised measure of academic achievement other than the matric exam, it is crucial that the assessments be continued in a strengthened form.

Important as these three policy interventions are, they are unlikely to be sufficient to close the learning gaps. This is why we have embarked on a research agenda to identify promising early-grade reading interventions. In particular, we want to find out how to lift the quality of teaching in the foundation phase.

Building on provincial innovations, particularly in Gauteng, the department of basic education is partnering with Wits School of Education to pilot and evaluate several reading support interventions on a large scale. Starting with literacy in the home language (Setswana) in 230 schools in the North West, the first major study is testing the effectiveness of using lesson plans, appropriate learning materials (such as graded readers) and building teachers’ capacity (either in the form of training or in-school coaching) and parent support.

The results after the first year in the North West study are encouraging, but the real effect of this study will only really be available by the middle of 2017.

The second of these large-scale studies, this time focusing on teaching pupils to read in English as an additional language, has just begun, with the partnership between the department and the Wits School of Education extending the research to test the viability of using new information technology to assist teachers to improve their instructional practices.

This and other university and government research partnerships, which make use of scientific research methods, will be the catalyst for improving the foundations of our education system.

Brahm Fleisch is a professor in the educational leadership and policy studies unit at the University of the Witwatersrand. Stephen Taylor is based in the office of the director general in the department of basic education.