Teachers bunk school more often than children – and they are also guilty of coming late to class after break time.

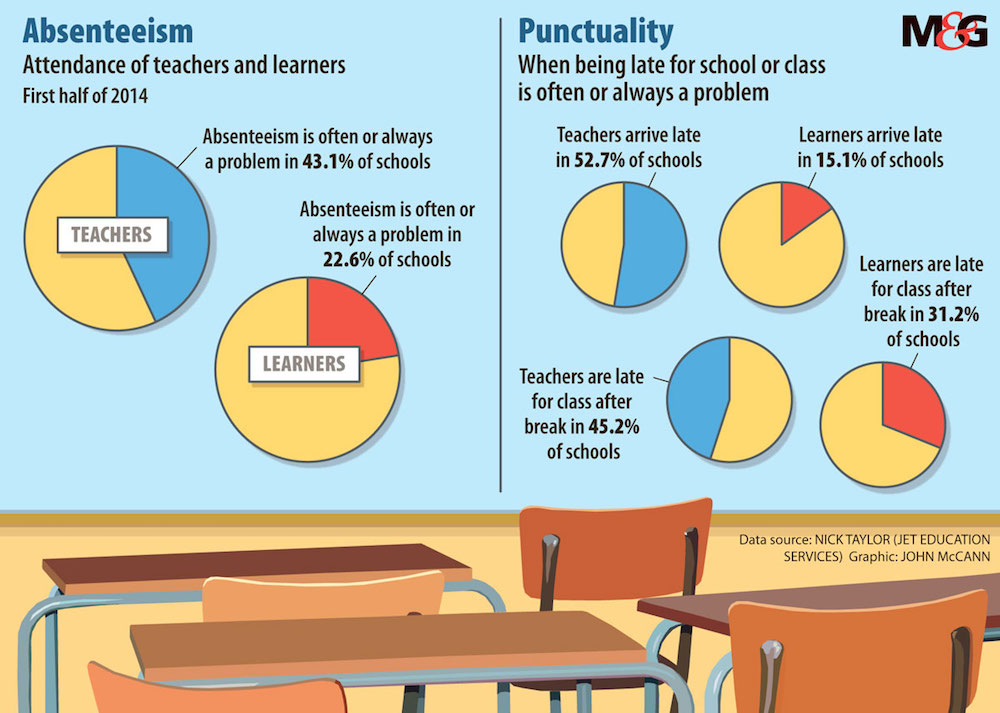

According to a draft report on the quality of high school education in South Africa, 40 out of the 93 schools surveyed reported that teacher attendance was often or always a problem, yet only a quarter of schools stated that learner absenteeism was a major issue.

The report’s findings follow an investigation by Dr Nick Taylor, a senior research fellow at JET Education Services, who gleaned information on teacher and learner absenteeism by examining attendance registers.

Punctuality was assessed through direct observations during school visits as well as in interviews with teachers and senior school managers.

“Such high levels of teacher absenteeism are a serious matter. Unlike individual learners who can catch up after an absence, if teachers are not at school, then their lessons are not delivered as planned and the time is lost entirely for all their learners,” the report stated.

The findings are likely to spark fresh calls to install an electronic clocking-in system at schools to monitor teacher attendance.

The South African Democratic Teachers Union (Sadtu) and the National Professional Teachers’ Organisation of South Africa (Naptosa) this week said that they would not support the introduction of such a system for teachers.

Sadtu’s deputy general secretary, Nkosana Dolopi, said a biometric machine “will not go and fetch the teacher at home and bring him to school”.

“What we need to address is the reasons teachers are absent from school. The conditions under which teachers are working are very strenuous. They are sick.”

Naptosa president Anthea Cereseto said the biometric system was problematic because it would turn professional people into clock-watchers.

“We want teachers to consider giving extra time after school to learners, whether it’s on the sports field or doing culturals or extra lessons. If you start with a clock, you are starting a mentality of clock-watching.”

In 2013, Motshekga told Parliament that teacher absenteeism in South Africa was the highest of all the Southern African Development Community countries.

The report stated that while “tardiness” among learners disadvantaged latecomers, teaching and learning could continue for the rest of the group. “But if the teacher does not arrive on time, then teaching and learning cannot commence and the whole class misses out.”

Teacher punctuality at school in the morning was often or always a problem at more than half of the schools surveyed, but only 17% of schools indicated that learners regularly arrived at school late.

Interestingly, just under half of the schools surveyed recorded that a teacher’s arrival in class after break time was frequently a problem.

The report described teacher late-coming as “very serious”, stating that “it negatively impacts entire classes that the teacher must serve”.

“As adult role models, it gives a bad example of the importance of timekeeping, and wasting lesson time undermines the value of teaching and learning and hence the purpose of school.”

Besides the problem of absenteeism and latecoming, the study also found that the 93 schools visited during the first six months of 2014 lost an average of 12.6 days each as a result of teachers attending training courses, sports meetings, music concerts, union meetings or memorial services.

“Union meetings and memorial services, which together account for a quarter of the total days lost, add no benefit whatsoever to teaching and learning – they are time wasted.”

At least two schools reported losing more than 15 days to union meetings and funerals. One school lost 13 days to music concerts and another three lost more than 15 days to sports events.

“This is excessive in terms of its impact on curriculum delivery. The consequence is significantly reduced learning opportunities, which result in learning gaps that negatively impact on attainment and may lead to learning difficulties in later years,” the report stated.

Taylor told the Mail & Guardian that from his recent experience of visiting a few schools, teacher absenteeism and late-coming is still a concern. “It’s become a culture in the majority of our schools to be very loose with time.”

He said if a biometric clocking-in system was introduced, it could provide excellent data on teacher punctuality and absenteeism.

“But there are caveats to the question as to whether it will improve the use of time in schools. First, these things tend to break down, and once that happens they will probably not be fixed quickly. Sabotage can’t be ruled out to ensure that they never work.”

He said even if the data was collected, the big problem was “holding people to account. This doesn’t happen anywhere in the school system, except in isolated areas. Managers are too timid and subordinates act with total impunity, as if it’s a right.”

But Dolopi said teachers did not “just stay away because they are truants. It’s not a deliberate act of just laziness. It’s because of their health status.” He said teachers taught in overcrowded classrooms and had to attend to social problems such as poverty that pupils brought to the classroom.

“These teachers are confronted with that situation on a daily basis. It’s common cause that it will affect their state of health.”

Cereseto said teaching was stressful, adding that unnecessary administration added to the burden.

“I am noticing an increase in teachers’ stress levels because of an increase in bureaucratic paperwork that teachers don’t really want to do because they don’t see it as productive. That’s what’s burning them out.”

Cereseto said disciplinary problems among schoolchildren also aggravated teacher stress levels.

“If you aren’t strong in the morning, or if you’re tired and overworked and you know you are going to face these particularly difficult learners, you could say to yourself: ‘I’m phoning in sick.’ There are schools in which disciplinary issues make each teaching day a nightmare for the teacher.”